Chapter Info (Click Here)

Book No. – 20 (Philosophy)

Book Name – Contemporary Theories of Knowledge – John L. Pollock

What’s Inside the Chapter? (After Subscription)

1. Motivation

2. Basic Beliefs

3. Epistemic Ascent

3.1. Defeasible Reasons

3.2. Justified Belief and Undefeated Arguments

3.3. The Problem of Perception

4. Reasoning and Memory

4.1. Occurrent Thoughts

4.2. Memory as a Source of Knowledge

4.3. Genetic Arguments and Dynamic Arguments

4.4. Primed Search

5. Reconsideration of Epistemologically Basic Beliefs

5.1. Incorrigible Appearance Beliefs

5.2. Problems with Incorrigible Appearance Beliefs

5.3. Prima Facie Justified Beliefs

5.4. Problems with Prima Facie Justified Beliefs

5.5. Problems with Foundationalism

Note: The first chapter of every book is free.

Access this chapter with any subscription below:

- Half Yearly Plan (All Subject)

- Annual Plan (All Subject)

- Philosophy (Single Subject)

- CUET PG + Philosophy

- UGC NET + Philosophy

Foundations Theories of Knowledge

Chapter – 2

Motivation

Until recently, the most popular epistemological theories were foundations theories.

Foundations theories are distinguished by granting a limited class of epistemologically basic beliefs a privileged epistemic status.

Basic beliefs are considered self-justifying and do not require further justification.

Nonbasic beliefs must be justified ultimately by appeal to these basic beliefs, forming a foundation for epistemic justification.

The motivation for foundations theories comes from the psychological observation that all knowledge comes through the senses.

Foundationalists identify sensory input as giving rise to epistemologically basic beliefs.

Other beliefs are derived by reasoning from these basic beliefs.

Reasoning can only justify beliefs if one is already justified in the premises; therefore, reasoning itself cannot be the ultimate source of justification.

Only perception can serve as the ultimate source of justification.

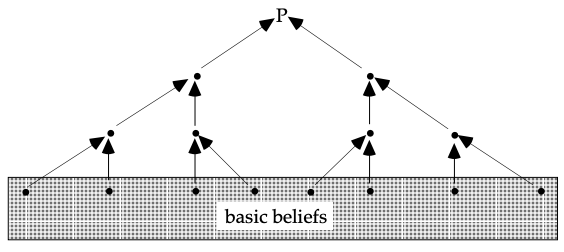

This leads to a pyramid model: basic beliefs from perception form the foundation, supporting all other justified beliefs through reasoning.

The foundationalist model has intuitive force because it is based on psychological truisms.

To develop a concrete epistemological theory, two issues must be addressed:

What kinds of beliefs are epistemologically basic and what qualifies them for their privileged role?

How are nonbasic beliefs justified by reasoning from basic beliefs?

The problem of reasoning in foundationalism is more subtle than often assumed.

A more nuanced version of foundationalism will be developed in the next section.

Basic Beliefs

Foundations theories are distinguished from coherence theories by positing a class of epistemologically basic beliefs with privileged epistemic status.

Basic beliefs must be justified independently of reasoning; if justification depends on reasoning, the belief is not basic.

The only beliefs not held on the basis of reasoning seem to be those directly from perception, so basic beliefs must be perceptual beliefs (in a sense to be clarified).

Perceptual beliefs about physical objects (e.g., seeing a door open, hearing sounds) can be mistaken due to illusions or misleading environments.

Perceptual beliefs are also influenced by expectations, which can cause misperceptions.

Since perceptual beliefs are fallible, they seem to need justification themselves, thus challenging their status as basic beliefs.

Traditional foundationalists deny that basic beliefs are ordinary perceptual beliefs; instead, they retreat to a weaker kind of belief.

Basic beliefs must be perceptual beliefs in some sense, but not necessarily about physical objects directly.

One might be mistaken about external objects but not about the character of one’s sensory experiences.

Thus, beliefs about sensory experiences (“appearance beliefs”) may serve as basic beliefs, while beliefs about physical objects are indirectly supported by reasoning from these.

The “appeared to” terminology helps describe sensory experiences, e.g., being “appeared to redly” to express how things appear rather than what they are.

This terminology distinguishes ordinary perceptual beliefs (claims about the world) from appearance beliefs (claims about how things appear).

The suggestion is that basic beliefs are appearance beliefs, motivated by the idea that physical-object perceptual beliefs are fallible, but appearance beliefs are not.

This relies on two presumptions: (1) if a belief can be mistaken, it is not basic; (2) appearance beliefs cannot be mistaken. Either could be denied.

For a foundations theory to work, basic beliefs must satisfy:

There must be enough basic beliefs to provide a foundation for all other justified beliefs.

Basic beliefs must have a secure epistemic status, i.e., be self-justifying without needing further justification.

Self-justifying belief means one can be justified in holding it simply by virtue of holding it, without independent reasons.

Incorrigibly justified belief is a stronger concept: a belief is incorrigibly justified if it is impossible to hold it unjustifiedly.

Few beliefs are incorrigibly justified; for example, believing “there is a book before me” can be held unjustifiedly.

Most beliefs fail to be incorrigibly justified, but appearance beliefs might be exceptions.

If basic beliefs are incorrigibly justified, they provide the firmest foundation for justification.

However, incorrigible justification is stronger than needed for basic beliefs.

Basic beliefs must allow for being justified without having reasons for them, but justification can be defeated by counter-evidence.

One must be prima facie justified in holding basic beliefs: justified unless there is reason to think otherwise.

Prima facie justified belief: a belief is prima facie justified if one can only hold it unjustifiedly when having reasons to doubt it; without such reasons, one is justified.