Chapter Info (Click Here)

Book Name – Essential Sociology (Nitin Sangwan)

Book No. – 28 (Sociology)

What’s Inside the Chapter? (After Subscription)

1. Great Tradition and Little Tradition

2. Idea of Development, Planning and Mixed Economy.

3. Constitution, Law and Social Change

4. Education and Social Change

Note: The first chapter of every book is free.

Access this chapter with any subscription below:

- Half Yearly Plan (All Subject)

- Annual Plan (All Subject)

- Sociology (Single Subject)

- CUET PG + Sociology

- UGC NET + Sociology

Vision of Social Change in India

Chapter – 19

India carries the legacy of colonial exploitation, which pushed millions into poverty and deprivation and imposed long-term backwardness on society.

Along with colonial impact, India also suffers from indigenous social evils.

At Independence, India had multiple developmental paths but chose a socialistic–democratic model, rejecting extreme capitalism, rigid socialism and monarchy.

Being primarily an agrarian economy, strong emphasis was laid on agriculture and rural development.

To revive the crippled economy, massive investment in the public sector was undertaken.

The Constitution was designed as a vehicle of social change, ensuring upliftment of disadvantaged sections.

Education received major priority, and institutions like the IITs were established on the lines of MIT.

Indian society has been shaped not only by colonial rule but also by internal evils such as the caste system, inequality, poverty and gender discrimination, making it a highly complex and multicultural society with many enduring fault lines.

Social change was visualised to improve the lives of the depressed classes, women, children and other weaker sections, with special emphasis on political equality for all.

Villages received special focus to improve both their economic and social conditions.

The vision of social change also aimed at emotional and political integration of India and at countering communalism, casteism and regionalism.

This vision is reflected in the Constitution and government policies, and the insertion of the word “socialist” underlined the national commitment to social change.

The Preamble, with ideals of fraternity, equality and liberty, defines this transformative vision.

Special legislations and safeguards were introduced for SCs, STs and women to realise these ideals.

As India was predominantly rural at Independence, land reforms were given high priority to bring social change in rural areas.

Technological changes in agriculture also strongly influence rural society, and the Green Revolution and its social upheavals are key examples.

Great Tradition and Little Tradition

The Little Tradition–Great Tradition framework was first used by Robert Redfield in his study of Mexican communities and later applied to India by Milton Singer and McKim Marriott in Village India: Studies in the Little Community, 1955, to explain social change through tradition and its social organisation.

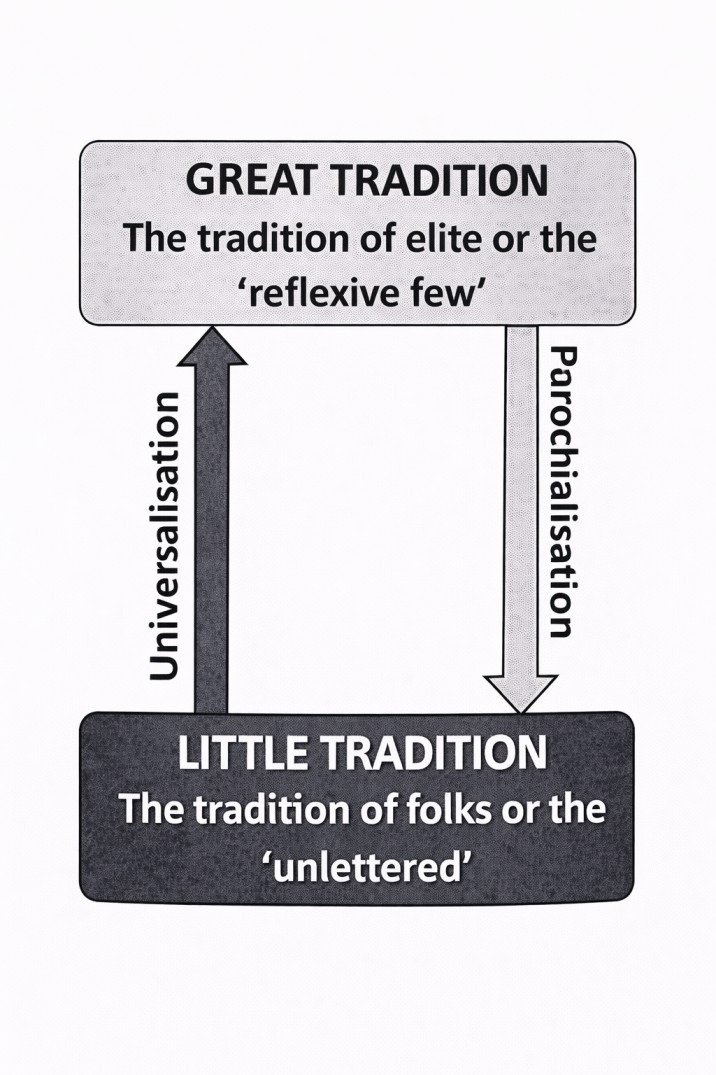

Social structure of a civilisation operates at two levels: the Little Tradition of folk or unlettered peasants (localised), and the Great Tradition of the elite or reflective few (diffusive), with continuous interaction between the two.

In India, Sanskritic rites (Great Tradition) are often added to non-Sanskritic rites (Little Tradition) in festivals, without replacing them, showing cultural synthesis.

Change follows an evolutionary–dialectic process with two stages: orthogenetic (indigenous, internal creativity) and heterogenetic (change through external contact), where transformation mainly occurs through heterogenetic processes.

Milton Singer argues that in India there is strong continuity and interdependence between Little and Great Traditions, and modernising forces are absorbed into tradition, visible in kinship, caste, values and festivals.

McKim Marriott, in his study of Kishangarhi village, shows that village culture contains both traditions, with universalisation (elements moving upward) and parochialisation (elements moving downward), helping maintain social unity and also explaining de-Sanskritisation.

According to Yogendra Singh, this framework explains only cultural change, not structural change, and the term “little” carries a biased sense of inferiority.

SC Dube rejects the simple binary and proposes multiple traditions, identifying a hierarchy of six traditions: classical, emergent national, regional, local, western and subcultural traditions.