Adjusting to Modern Life

Chapter – 1

Introduction

- The immense Boeing 747 lumbers into position to accept its human cargo.

- Passengers make their way on board, eager for their journey.

- Air traffic controllers diligently monitor radar screens, radio transmissions, and digital readouts of weather information from a tower a few hundred yards away.

- At the reservation desk in the airport terminal, clerks punch up the appropriate ticket information on their computers and quickly process the steady stream of passengers.

- Mounted on the wall are video screens displaying up-to-the-minute information on flight arrivals, departures, and delays, keeping everyone informed.

- Back in the cockpit of the plane, the flight crew calmly scan the complex array of dials, meters, and lights to assess the aircraft’s readiness for flight.

- In a few minutes, the airplane will slice into the cloudy, snow-laden skies above Chicago.

- In a little over three hours, its passengers will be transported from the piercing cold of a Chicago winter to the balmy beaches of the Bahamas.

- Another everyday triumph for technology will have taken place, seamlessly connecting distant places and climates.

THE PARADOX OF PROGRESS

Point:

- Modern technology has provided us with countless time-saving devices like automobiles, telephones, vacuum cleaners, dishwashers, photocopiers, and personal computers.

- Cell phones with headsets allow multitasking, such as talking to friends or colleagues while battling rush hour traffic.

- Personal computers can perform calculations in seconds that would take months if done by hand.

Counterpoint:

- Despite these time-saving devices, many complain about not having enough time.

- Schedules overflow with appointments, commitments, and plans, leading to a subjective feeling of having less time.

- Work often follows people home, tethering them to their jobs around the clock with tools like cell phones, pagers, and wireless email.

- To cope with the time crunch, people are sacrificing sleep, leading to an epidemic of sleep deprivation in American society.

- Chronic sleep loss can have significant negative effects on individuals’ daytime functioning, mental health, and physical health.

Point:

- The range of life choices available in modern societies has increased exponentially in recent decades.

- Barry Schwartz (2004) illustrates this with examples from consumer choices, such as selecting from 285 varieties of cookies, 61 suntan lotions, 150 lipsticks, and 175 salad dressings at a local supermarket.

- Increased choice extends beyond consumer goods into significant domains of life, including education, work, intimate relationships, and personal appearance.

- Flexibility in college curricula and the rise of online education provide unprecedented opportunities for education choices.

- Telecommuting offers employees new choices in how and where they work, influencing work-life balance.

- People have increased freedom to make choices about their intimate relationships, including delaying marriage, cohabiting, or choosing not to have children.

- Advances in plastic surgery have made personal appearance a matter of choice, allowing individuals to alter their looks according to their preferences.

Counterpoint:

- Recent research suggests that an overabundance of choices leads to “choice overload,” causing individuals to struggle with decisions.

- Studies indicate that decision dilemmas resulting from too many choices can deplete mental resources and undermine self-control.

- Complexity in decision-making increases the likelihood of errors and contributes to rumination, postdecision regret, and anticipated regret.

- Choice overload ultimately undermines individuals’ happiness and contributes to depression, according to Schwartz (2004).

- Research data show an increase in the incidence of depressive disorders over the last 50 years, suggesting a correlation with choice overload (Hidaka, 2012).

- Average anxiety levels have substantially increased in recent decades, indicating that increased freedom of choice has not resulted in enhanced tranquility or improved mental health (Twenge, 2000, 2011).

Point:

- Modern technology has provided unprecedented control over the world around us.

- Advances in agriculture, such as genetically modified crops, have dramatically increased food production and reliability.

- Elaborate water supply systems, comprising canals, tunnels, pipelines, dams, reservoirs, and pumping stations, enable the growth of massive metropolitan areas in inhospitable deserts.

- Progress in medicine allows for remarkable feats such as reattaching severed limbs, correcting microscopic defects in the eye using lasers, and replacing the human heart.

- These advancements demonstrate the power of technology to improve human life and overcome natural limitations.

Counterpoint:

- Modern technology has had a devastating negative impact on the environment.

- It has contributed to global warming, leading to climate change.

- Destruction of the ozone layer has resulted from the release of ozone-depleting substances.

- Deforestation has occurred at alarming rates, disrupting ecosystems and contributing to loss of biodiversity.

- Exhaustion of much of the world’s fisheries due to overfishing threatens marine ecosystems.

- Widespread air and water pollution have resulted from industrial activities, transportation, and agricultural practices.

- Plants and animals are extensively exposed to toxic chemicals, leading to ecosystem degradation and health risks.

- Many experts worry that continued environmental degradation will deplete Earth’s resources, jeopardizing the quality of life for future generations.

- These environmental crises are exacerbated by overconsumption and waste, indicating behavioral problems in addition to technical challenges.

- Excessive consumption of natural resources in North America and Europe is a crucial issue, with ecological footprints far exceeding sustainable levels.

- The paradox of progress is evident in the lack of perceptible improvement in collective health and happiness despite impressive technological advances.

- Alvin Toffler (1980) attributes collective alienation and distress to being overwhelmed by rapidly accelerating cultural change.

- Robert Kegan (1994) suggests that the mental demands of modern life have become so complex, confusing, and contradictory that many individuals feel “in over our heads.”

- Tim Kasser (2002) speculates that excessive materialism weakens social ties, fuels insecurity, and undermines collective well-being.

- Micki McGee (2005) proposes that modern changes in gender roles, job stability, and social trends foster an obsession with self-improvement, undermining security and satisfaction with identity.

- McGee identifies a “makeover culture” nurturing the belief that individuals can reinvent themselves as needed, but this creates tremendous pressures fostering anxieties.

- Sherry Turkle (2011) asserts that in the modern, digitally connected world, people spend more time with technology and less with each other.

- Despite accumulating “friends” on social media, Americans report having fewer real friends, deepening feelings of loneliness and isolation.

- The reliance on superficial online communication exacerbates the intimacy deficit, leaving more people suffering from a lack of genuine connection.

- Many theorists, from various perspectives, agree that the fundamental challenge of modern life is the search for meaning, direction, and a personal philosophy.

- This search involves grappling with issues such as forming a solid sense of identity, establishing coherent values, and envisioning a future that realistically promises fulfillment.

- Problems of this nature were likely much simpler centuries ago.

- In contemporary times, many individuals find themselves struggling in a sea of confusion, lacking clarity and direction in their lives.

THE SEARCH FOR DIRECTION

- The rapid pace of social and technological change in modern times often leads to feelings of anxiety and uncertainty.

- Individuals seek to alleviate these feelings by searching for a sense of direction and purpose in their lives.

- Many Americans have invested significant sums of money in self-realization programs like Scientology, Silva Mind Control, John Gray’s Mars and Venus relationship seminars, and Tony Robbins’s Life Mastery seminars.

- These programs promise profound enlightenment and rapid life transformation, leading many participants to claim revolutionary changes in their lives.

- However, most experts criticize such programs as intellectually bankrupt and expose them as lucrative money-making schemes.

- Book and magazine exposés reveal the financial benefits reaped by program inventors like Tony Robbins ($80 million in annual income), Dr. Phil ($20 million in annual income), and John Gray ($50,000 per speech).

- Steve Salerno (2005) provides a scathing critique of these programs, highlighting the hypocrisy and inflated credentials of leading self-help gurus.

- Salerno exposes the dubious academic backgrounds of some gurus and criticizes their personal histories, including allegations of marital infidelity and hypocrisy regarding their own lifestyles.

- Despite criticisms, the enormous success of these self-help gurus and programs underscores the desperation of some individuals for a sense of direction and purpose in their lives.

- Self-realization programs are often harmless scams that provide participants with an illusory sense of purpose or a temporary boost in self-confidence.

- However, in some cases, these programs can lead individuals down ill-advised pathways that prove harmful.

- In October 2009, a tragic incident occurred in Sedona, Arizona, where three people died and eighteen others were hospitalized, many with serious injuries, after participating in a “spiritual warrior” retreat.

- The retreat, run by James Ray, a popular self-help guru, required participants to spend hours in a makeshift sweat lodge.

- Ray’s website promises to teach people how to trigger their unconscious mind to increase wealth and fulfillment automatically.

- Ray, who has written inspirational books and appeared on popular TV talk shows, has built a $9-million-a-year self-help empire.

- Participants in the ill-fated retreat paid over $9,000 each for the privilege of attending.

- After spending 36 hours fasting in the desert on a “vision quest,” participants were led into a tarp-covered sweat lodge for an endurance challenge meant to demonstrate gaining confidence by conquering physical discomfort.

- The poorly ventilated and overheated sweat lodge led to participants vomiting, gasping for air, and collapsing within an hour of the ceremony’s start.

- Despite the dangerous conditions, James Ray urged his followers to persevere, claiming that vomiting was beneficial and insisting they push through the discomfort.

- While no one was physically forced to stay, Ray’s intimidating presence and strong exhortations pressured participants to remain.

- Tragically, many participants became seriously ill by the end of the ceremony.

- Witnesses reported that at the conclusion of the ceremony, Ray emerged triumphantly, seemingly unaware of the unconscious bodies around him.

- After the event, Ray provided a partial refund to the family of Kirby Brown, one of the participants who died.

- Despite the tragedy, some of Ray’s followers continued to enthusiastically champion his vision for self-improvement.

- This unwavering faith in Ray’s teachings highlights the persuasive power of charismatic leaders who promote self-realization programs.

- In 2011, an Arizona jury convicted Ray on three counts of negligent homicide after less than 12 hours of deliberation.

- Unorthodox religious groups, commonly referred to as cults, attract numerous converts who willingly embrace regimentation, obedience, and zealous ideology.

- One study suggested that more than 2 million young adults are involved with cults in the United States.

- Cults often operate in obscurity, unless notable incidents such as mass suicides attract public attention.

- While it’s widely believed that cults use brainwashing and mind control tactics, converts are typically normal people influenced by sophisticated social influence strategies.

- People join cults because they offer simple solutions to complex problems, a sense of purpose and belongingness, and a structured lifestyle that reduces uncertainty.

- Factors like alienation, identity confusion, and weak community ties make some individuals particularly vulnerable to cult seduction.

- In a more mundane example, the nationally syndicated personality “Dr. Laura” Schlessinger offers blunt, judgmental advice to millions of listeners.

- Despite only a few callers getting through to her during each show, an astonishing 75,000 people call daily seeking her advice.

- Dr. Laura, not a psychologist or psychiatrist but with a doctorate in physiology, analyzes callers’ problems from a moral rather than psychological framework.

- Her confrontational style lacks empathy and often involves preaching about how people ought to lead their lives.

- Despite criticism for her divisive advice, Dr. Laura’s popularity demonstrates the widespread eagerness for guidance and direction.

Self-Help Books

- Americans spend approximately $650 million annually on self-help books, indicating a significant interest in personal development.

- Including self-help audiotapes, CDs, DVDs, software, Internet sites, lectures, seminars, and life coaching, the self-improvement industry amounts to a $10 billion-a-year industry, according to Marketdata Enterprises.

- This fascination with self-improvement is longstanding, with American readers showing a voracious appetite for self-help books for decades.

- Popular self-help titles include “I’m OK—You’re OK” (Harris, 1967), “The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People” (Covey, 1989), “Ageless Body, Timeless Mind” (Chopra, 1993), “Don’t Sweat the Small Stuff . . . and It’s All Small Stuff” (Carlson, 1997), “The Purpose Driven Life” (Warren, 2002), “The Secret” (Byrne, 2006), “Become a Better You: Seven Keys to Improving Your Life Every Day” (Osteen, 2009), “The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business” (Duhigg, 2012), and “You’re Stronger Than You Think” (Parrott, 2012).

- Despite the promises of these books to change the quality of life, merely reading a book is unlikely to turn one’s life around.

- The consumption of self-help literature is not as helpful as publishers claim, as evidenced by the continued prevalence of anxiety and depression in recent decades.

- The abundance of self-help books on bookstore shelves reflects society’s collective distress and ongoing search for the elusive secret of happiness.

The Value of Self-Help Books

- Not all self-help books should be dismissed, as they vary widely in quality and effectiveness.

- Surveys of psychotherapists’ opinions suggest that there are excellent self-help books offering authentic insights and sound advice.

- Many therapists recommend carefully selected self-help books to their patients.

- Some self-help books have been tested in clinical trials with favorable results, although these studies often have methodological weaknesses.

- Dismissing all self-help books as shallow drivel would be foolish, as some offer valuable insights and advice.

- However, many self-help books suffer from four fundamental shortcomings.

- Firstly, they are dominated by “psychobabble,” using vague and trendy language that lacks clarity and meaning.

- Terms like “It’s beautiful if you’re unhappy” and “You need a real high-energy experience” exemplify this vague and often meaningless jargon.

- Such language sacrifices clarity and impedes effective communication rather than enhancing it.

- Emphasis on Sales over Scientific Soundness:

- Self-help books often prioritize sales over scientific validity.

- Advice is frequently speculative, based on authors’ intuitive analyses rather than solid research.

- Therapeutic interventions effective in clinical settings may not work without professional guidance.

- Publishers may exaggerate claims on book covers, despite authors’ intentions.

- Lack of Explicit Behavioral Guidance:

- Self-help books typically lack explicit directions on behavior change.

- While they effectively resonate with readers by describing common problems, the solutions offered are often vague and could be condensed into a fraction of the book’s length.

- Inspirational cheerleading substitutes for concrete advice.

- Promotion of Self-Centeredness and Narcissism:

- Many self-help books encourage a self-centered, narcissistic approach to life.

- Narcissism, marked by an inflated sense of importance and a tendency to exploit others, is often promoted.

- Some books propagate a “me first” philosophy, advocating for doing whatever one feels like without considering consequences for others.

- This mentality began to emerge notably in the 1970s, emphasizing self-admiration, entitlement, and exploitative interpersonal relationships.

- Research suggests a rise in narcissism levels, potentially influenced by self-help literature.

What to Look for in Self-Help Books

- Clarity in Communication:

- Seek books with clear and understandable advice to ensure its practicality.

- Avoid those filled with jargon and psychobabble that hinder comprehension.

- Realistic Promises:

- Choose books that temper expectations and acknowledge the challenge of behavior change.

- Beware of exaggerated promises, such as instant cures for complex issues like phobias or failing marriages.

- Author Credentials:

- Research the authors’ credentials to gauge their expertise.

- Use online resources for objective biographical information and insightful reviews.

- Theoretical or Research Basis:

- Prefer books that mention or briefly discuss the theoretical or research basis for the advocated program.

- Ensure the advice is grounded in published research, accepted theory, or clinical evidence rather than mere speculation.

- Look for books with references or citations supporting their claims.

- Detailed Behavioral Instructions:

- Select books that offer explicit and detailed directions on behavior change.

- The quality of these instructions is crucial as they form the core of the book’s utility.

- Specialization and Depth:

- Favor books focusing on specific problems like overeating, loneliness, or marital difficulties over those claiming to solve all life’s problems.

- Specialized books tend to offer more depth and insight, authored by experts in their respective fields, making them more valuable resources.

The Approach of This Textbook

- Introduction to Human Behavior Research:

- The book aims to summarize scientific research on human behavior relevant to modern living, drawing primarily from psychology.

- It addresses common personal problems such as anxiety, stress, relationships, frustration, loneliness, depression, and self-control.

- Realistic Approach to Personal Challenges:

- Unlike self-help books and programs, it refrains from making bold promises about solving personal problems or transforming lives, acknowledging the difficulty of behavior change.

- Recognizes the challenging nature of changing behavior, which may require significant time and effort, often without immediate solutions.

- Potential for Personal Growth:

- Encourages optimism about personal growth and behavior change, suggesting that individuals can indeed change their behavior, often without professional intervention.

- Emphasizes the importance of realistic expectations, acknowledging that reading the book won’t provide revelatory experiences or unveil mysterious secrets.

- Providing Useful Information:

- Asserts the book’s potential to offer useful information and guide readers toward beneficial directions.

- Highlights the reader’s role in utilizing the information provided, emphasizing personal responsibility in applying the knowledge gained from the text.

- The text emphasizes the value of accurate knowledge in psychology for everyday life, suggesting that understanding human behavior can aid in interactions with others and self-understanding.

- It aims to cultivate a critical attitude towards psychological issues, promoting systematic, skeptical scrutiny of ideas. Critical thinking skills are highlighted as essential for evaluating information effectively.

- The text acknowledges its broad coverage may lack depth in some areas but presents itself as a resource to introduce readers to further exploration in related topics, techniques, or therapies.

- Taking charge of one’s life is considered crucial for effective adjustment, advocating for proactive measures in improving one’s quality of life rather than passive acceptance or avoidance of problems.

THE PSYCHOLOGY OF ADJUSTMENT

What Is Psychology?

- The text emphasizes the value of accurate knowledge in psychology for everyday life, suggesting that understanding human behavior can aid in interactions with others and self-understanding.

- It aims to cultivate a critical attitude towards psychological issues, promoting systematic, skeptical scrutiny of ideas. Critical thinking skills are highlighted as essential for evaluating information effectively.

- The text acknowledges its broad coverage may lack depth in some areas but presents itself as a resource to introduce readers to further exploration in related topics, techniques, or therapies.

- Taking charge of one’s life is considered crucial for effective adjustment, advocating for proactive measures in improving one’s quality of life rather than passive acceptance or avoidance of problems.

- Psychology has a practical dimension, with many psychologists offering professional services to the public alongside academic pursuits.

- Prior to the 1950s, psychologists were primarily found in academic settings, engaged in teaching and research.

- The demands of World War II led to the rapid growth of clinical psychology as a professional specialty.

- Clinical psychology focuses on diagnosing and treating psychological problems and disorders.

- During World War II, academic psychologists were enlisted as clinicians to screen military recruits and provide treatment to traumatized soldiers.

- The experience of clinical work during the war sparked interest among psychologists, leading to the establishment of training programs to meet the growing demand for clinical services.

- As a result, a significant portion of new Ph.D.’s in psychology began specializing in clinical work, marking a maturation of psychology as a profession.

What Is Adjustment?

- Adjustment, borrowed from biology’s concept of adaptation, refers to psychological processes through which individuals manage or cope with the demands and challenges of everyday life.

- Similar to how species adapt to changes in their environment, individuals must adjust to various circumstances such as new jobs, financial setbacks, or loss of loved ones.

- The study of adjustment encompasses a wide range of topics reflecting the diversity of demands in daily life.

- Early chapters address general issues including how personality influences adjustment patterns, the impact of stress on individuals, and coping strategies.

- Subsequent chapters explore adjustment in interpersonal contexts, covering topics such as prejudice, persuasion, social conflict, group behavior, friendship, love, marriage, divorce, gender roles, career development, and sexuality.

- Later sections of the book delve into how adjustment influences psychological health, the treatment of psychological disorders, and the emerging field of positive psychology.

- The study of adjustment permeates various aspects of human life, indicating the broad scope of issues to be discussed.

- Before delving into specific topics, an understanding of psychology’s approach to investigating behavior through the scientific method is essential.

THE SCIENTIFIC APPROACH TO BEHAVIOR

- Individuals often invest significant effort in understanding both their own behavior and the behavior of others, pondering various behavioral questions.

- Common queries include personal anxieties in social interactions, attention-seeking behaviors, infidelity despite having a seemingly good relationship, personality trait comparisons like extraversion and introversion, and seasonal variations in mental health like depression during holidays.

- While many people seek explanations for behavior, the principal distinction lies in psychology’s commitment to empiricism as a science.

- Psychology endeavors to explain behavior through systematic observation, experimentation, and empirical evidence, distinguishing it from anecdotal or speculative explanations.

- Psychologists employ scientific methods to investigate behavior, including hypothesis testing, controlled experiments, and statistical analysis, aiming for objective and replicable findings.

- This scientific approach allows psychologists to develop theories and models that provide systematic explanations for behavior, contributing to the advancement of knowledge in the field.

- By adhering to empiricism, psychology seeks to offer reliable and evidence-based insights into human behavior, distinguishing it from lay interpretations or common beliefs.

The Commitment to Empiricism

- Empiricism in scientific psychology asserts that knowledge should be obtained through observation rather than solely relying on reasoning, speculation, traditional beliefs, or common sense.

- Scientific psychology’s empirical nature means its conclusions are derived from systematic observation, distinguishing it from informal, subjective speculations.

- Scientists in psychology don’t settle for ideas that sound plausible but conduct research to test them empirically.

- Everyday speculations tend to be informal, unsystematic, and subjective, while scientific investigations are formal, systematic, and objective.

- In scientific investigations, researchers formulate testable hypotheses, collect relevant data through observation, employ statistical analysis to interpret these data, and communicate their findings typically through publication in technical journals.

- Publishing scientific studies enables other experts to assess and critique new research findings, fostering transparency and accountability in the scientific process.

Advantages of the Scientific Approach

- While science is not the sole method for drawing conclusions about behavior, other approaches include logic, casual observation, and common sense.

- The empirical approach of science offers two major advantages: clarity and precision, and relative intolerance of error.

- Common sense notions about behavior tend to be vague and ambiguous, leading to disagreements and misunderstandings. In contrast, the empirical approach requires precise specification of hypotheses, enhancing communication and understanding.

- Scientists subject their ideas to empirical tests and scrutinize each other’s findings critically, demanding objective data and thorough documentation.

- The scientific approach seeks to resolve conflicting findings through further research, promoting accuracy and reliability.

- Common sense and casual observation often tolerate contradictory generalizations and involve little effort to verify ideas, leading to the widespread belief in myths about behavior.

- While science doesn’t claim a monopoly on truth, its empirical approach tends to yield more accurate and dependable information compared to casual analyses and speculation.

- Empirical data provide a useful benchmark for evaluating claims and information from other sources.

- Understanding the scientific enterprise lays the groundwork for examining specific research methods in psychology, with experimental and correlational methods being the main types discussed separately due to their important distinctions.

Experimental Research: Looking for Causes

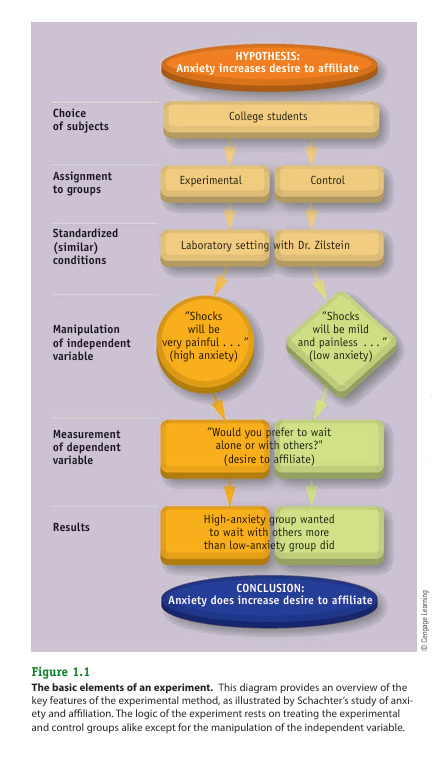

- Social psychologist Stanley Schachter was intrigued by the question of whether misery seeks company, i.e., whether people experiencing anxiety prefer to be alone or seek the company of others.

- Schachter hypothesized that increases in anxiety would lead to increases in the desire for affiliation, or the need to be with others.

- To test this hypothesis, Schachter designed a clever experiment in 1959.

- The experiment involved manipulating one variable (independent variable), such as anxiety levels, under carefully controlled conditions.

- The researcher then observed whether any changes occurred in a second variable (dependent variable), such as the desire for affiliation.

- This experiment exemplifies the experimental method, wherein researchers manipulate variables to observe their effects on other variables under controlled conditions.

- Psychologists rely heavily on the experimental method as it allows for causal inferences and provides insights into relationships between variables.

Independent and Dependent Variables

- In an experiment, the goal is to determine how changes in one variable (denoted as x) influence changes in another variable (referred to as y), investigating the impact of x on y.

- The variable x is termed the independent variable, which the experimenter manipulates or controls to observe its effects on another variable.

- The independent variable is hypothesized to have an effect on the dependent variable, y, and the experiment aims to verify this effect.

- The dependent variable is the variable thought to be influenced by the manipulations of the independent variable.

- In psychology studies, the dependent variable often measures some aspect of subjects’ behavior.

- In Stanley Schachter’s experiment, the independent variable was the participants’ anxiety level, manipulated by informing them about the anticipated intensity of electric shocks.

- Participants were divided into two groups: the high-anxiety group, informed of impending painful shocks, and the low-anxiety group, told about mild and painless shocks.

- These procedures aimed to evoke different levels of anxiety among participants.

- Contrary to what participants were led to believe, no shocks were administered during the experiment.

- Instead, participants were asked whether they preferred to wait alone or in the company of others, serving as a measure of their desire to affiliate with others, which was the dependent variable in the study.

Experimental and Control Groups

- In an experiment, researchers typically assemble two groups of participants: the experimental group and the control group.

- The experimental group receives special treatment regarding the independent variable, while the control group does not receive this special treatment.

- In Stanley Schachter’s study, participants in the high-anxiety condition constituted the experimental group, receiving treatment to induce high anxiety, while those in the low-anxiety condition comprised the control group.

- It’s essential for the experimental and control groups to be similar in all aspects except for the treatment related to the independent variable.

- This similarity ensures that any differences observed between the groups on the dependent variable are attributable to the manipulation of the independent variable.

- By isolating the impact of the independent variable on the dependent variable, researchers can draw conclusions about their relationship.

- In Schachter’s experiment, increased anxiety led to increased affiliation, as predicted.

- The experimental method relies on the assumption that the experimental and control groups are alike in all important aspects except for their treatment regarding the independent variable.

- Any other differences between the groups can confound the results and hinder drawing solid conclusions about the relationship between the independent and dependent variables.

Advantages and Disadvantages

- The experiment is a powerful research method due to its ability to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables.

- Precise control in experiments allows researchers to isolate the relationship between the independent variable and the dependent variable, enabling conclusions about causation.

- No other research method can replicate the experimental method’s advantage in establishing causation.

- Despite its strengths, the experimental method has limitations.

- One limitation is that researchers may be interested in variables that cannot be manipulated as independent variables due to ethical concerns or practical constraints.

- For example, studying the effects of being brought up in urban versus rural areas on people’s values would require assigning similar families to live in different environments, which is impossible.

- In such cases, researchers must turn to correlational research methods to explore the relationships between variables.

Correlational Research: Looking for Links

Measuring Correlation

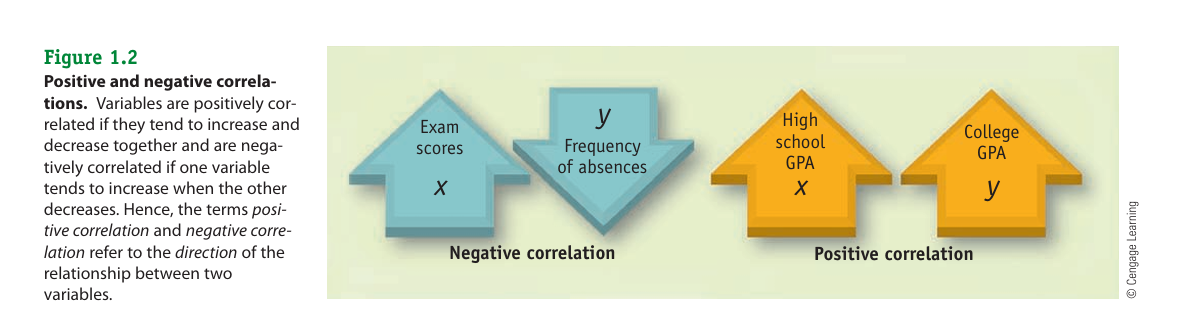

- Correlation refers to the association or link between two variables when researchers cannot exert experimental control over them.

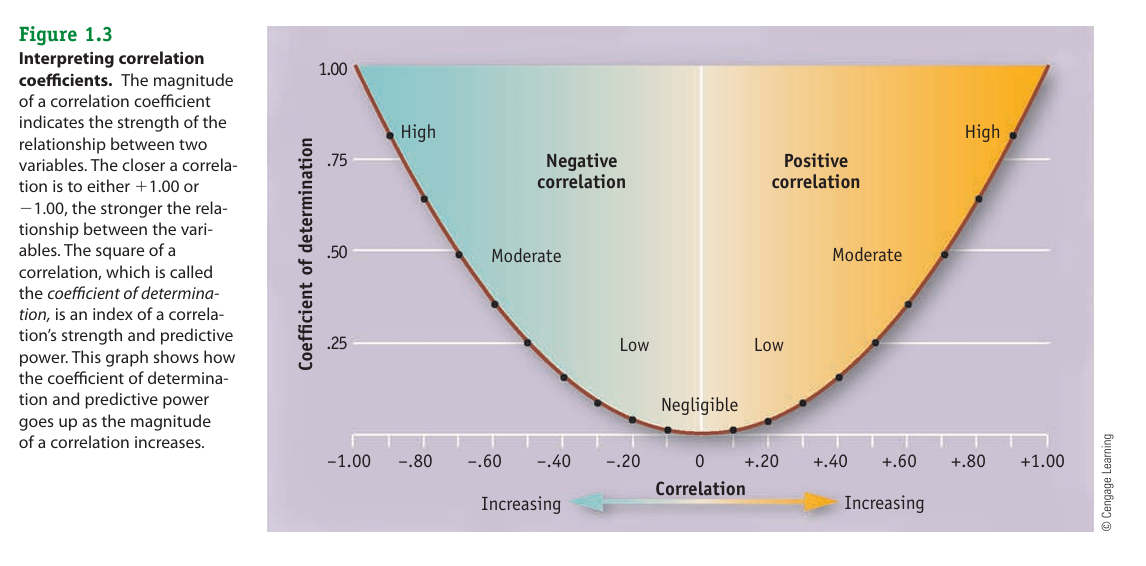

- A correlation exists when two variables are related to each other, and the strength and direction of this relationship are typically measured using a correlation coefficient.

- The correlation coefficient is a numerical index indicating the degree of relationship between two variables.

- It reveals both the strength of the relationship and its direction, which can be positive or negative.

- A positive correlation indicates that two variables co-vary in the same direction, meaning high scores on one variable are associated with high scores on the other, and vice versa.

- For instance, there’s a positive correlation between high school GPA and subsequent college GPA, indicating that students who perform well in high school tend to perform well in college.

- In contrast, a negative correlation suggests that two variables co-vary in the opposite direction, where high scores on one variable are associated with low scores on the other, and vice versa.

- An example of a negative correlation is seen in college courses, where there’s typically a negative correlation between the frequency of student absences and exam performance. High absenteeism tends to be associated with low exam scores, while low absenteeism is associated with higher exam scores.

- The positive or negative sign of a correlation coefficient indicates whether the association between variables is direct or inverse, respectively.

- The magnitude of the correlation coefficient reflects the strength of the association between variables.

- A correlation coefficient can range from 0 to +1.00 (if positive) or from 0 to -1.00 (if negative).

- A coefficient close to zero indicates no relationship between the variables.

- The closer the correlation coefficient is to either -1.00 or +1.00, the stronger the relationship between the variables.

- For example, a correlation of +0.90 indicates a stronger association between variables compared to a correlation of +0.40.

- Similarly, a correlation of -0.75 represents a stronger relationship than a correlation of -0.45.

- The strength of a correlation depends solely on the size of the coefficient, while the positive or negative sign signifies the direction of the relationship.

- Therefore, a correlation coefficient of -0.60 indicates a stronger relationship than a coefficient of +0.30, irrespective of the sign.

- Correlational research methods encompass various approaches such as naturalistic observation, case studies, and surveys.

- Researchers utilize these methods to detect associations between variables and explore relationships in natural settings or through data collection from individuals.

Naturalistic Observation

- Naturalistic observation involves careful observation of behavior without direct intervention from the researcher, allowing behavior to unfold naturally in its usual environment.

- Researchers conduct naturalistic observation to study behavior in its natural setting, where it would typically occur without interference.

- Systematic planning is necessary to ensure consistent and methodical observations during naturalistic observation studies.

- An example of naturalistic observation is a study by Ramirez-Esparza and colleagues (2009) that examined ethnic differences in sociability using an electronically activated recorder (EAR).

- The EAR is a portable audio recorder carried by participants that periodically records their conversations and ambient sounds during their daily activities.

- Ramirez-Esparza and colleagues used the EAR to investigate a paradox regarding stereotypes of Mexican sociability compared to Americans.

- Stereotypes suggest that Mexicans are outgoing and sociable, yet when self-rated, they tend to rate themselves as less sociable than Americans.

- The study found that Mexican participants rated themselves as less extroverted than American participants but data from the EAR revealed that Mexicans were actually more sociable than their American counterparts in daily behavior.

- The major strength of naturalistic observation is its ability to study behavior in conditions that are less artificial than those in experiments, providing valuable insights into behavior in real-world settings.

Case Studies

- A case study involves an in-depth investigation of an individual subject, typically conducted in clinical settings where psychologists aim to diagnose and treat psychological problems.

- Clinicians utilize various procedures in case studies, including interviewing the individual, interviewing others familiar with the individual, direct observation, examination of records, and psychological testing.

- Case studies are not usually conducted as empirical research for diagnostic purposes; instead, they involve analyzing a collection or series of case studies to identify patterns and draw general conclusions.

- For example, a study by Arcelus et al. (2009) evaluated the effectiveness of a revised version of interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) for individuals with bulimia, an eating disorder characterized by episodes of overeating followed by purging behaviors.

- Over a two-year period, 59 bulimic patients underwent IPT treatment at an eating disorders clinic in Great Britain. Case histories were compiled, and patients underwent psychological testing to assess their eating pathology and psychological functioning.

- Assessments were conducted at various points during and after the sixteen-session course of IPT treatment.

- The results indicated that interpersonal therapy can be an effective treatment for bulimic disorders.

- Case studies are particularly useful for investigating phenomena such as the origins of psychological disorders and evaluating the effectiveness of specific therapeutic approaches.

Surveys

- Surveys serve as structured questionnaires to gather information about specific aspects of participants’ behavior, commonly utilized in correlational research.

- They are frequently employed to measure attitudes and behaviors that are challenging to observe directly, such as marital interactions.

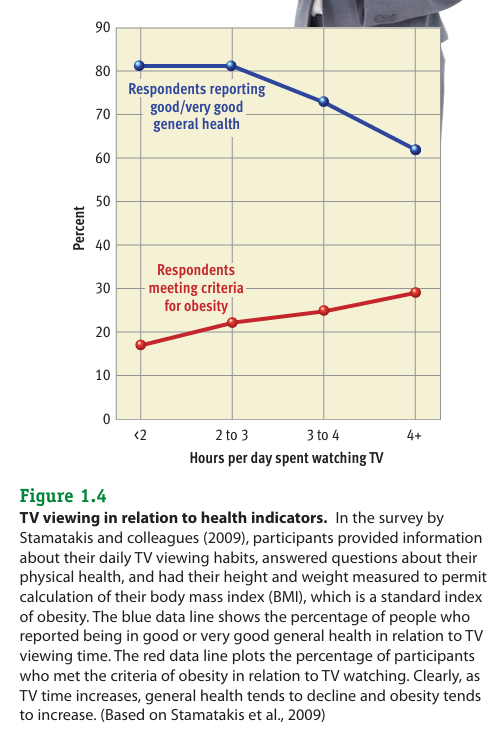

- Stamatakis and colleagues (2009) conducted household interviews with nearly 8000 adult participants in Scotland.

- Participants were queried about their daily screen-based entertainment time, including TV, video games, and computer material.

- Additionally, participants completed questionnaires regarding physical activity, general health, cardiovascular health, and demographic characteristics like income and education.

- Height and weight measurements enabled the calculation of participants’ body mass index (BMI), a key indicator of obesity.

- Survey data unveiled a clear association between increased screen time and compromised health, with higher TV viewing correlating with higher rates of obesity, doctor-diagnosed diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and lower reports of general health.

- Notably, the data revealed a significant link between lower socioeconomic status and prolonged screen-based entertainment time, indicating that individuals from lower social classes spent more time in front of screens.

- These findings highlighted the health risks associated with sedentary behavior and underscored socioeconomic status as a crucial factor influencing screen time habits.

Advantages and Disadvantages

Advantages of Correlational Research:

- Enables exploration of questions that cannot be examined through experimental procedures.

- Broadens the scope of phenomena psychologists can study.

- Facilitates the collection of insightful data on relationships between variables, as seen in the study on sedentary behavior and health conducted by Stamatakis and colleagues (2009).

Disadvantages of Correlational Research:

- Lacks the ability to control events to isolate cause and effect.

- Cannot conclusively demonstrate causal relationships between variables.

- Correlation does not imply causation; finding a correlation between variables like x and y only indicates a relationship, without elucidating the direction or cause of that relationship.

- Example: Survey studies indicate a positive correlation between relationship satisfaction and sexual satisfaction (Schwartz & Young, 2009), but it’s challenging to determine causation. It’s unclear whether good sex leads to healthy relationships, vice versa, or both are influenced by a third variable like compatibility in values.

- Illustrates the “third-variable problem,” where multiple causal relationships are plausible, as shown in Figure 1.5.

- This issue is common in correlational research and complicates interpretation by introducing the possibility of third variables influencing the observed correlation.

THE ROOTS OF HAPPINESS: AN EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS

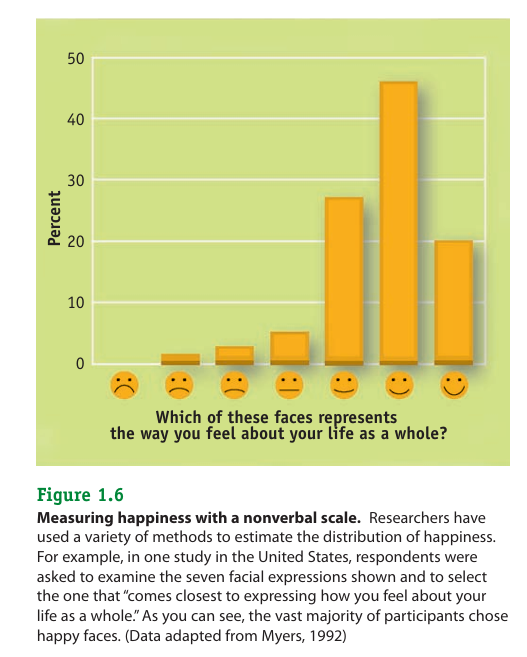

- Social scientists have begun empirically testing various hypotheses about the determinants of happiness through survey studies.

- These studies focus on subjective well-being, which refers to individuals’ personal assessments of their overall happiness or life satisfaction.

- Contrary to common assumptions, empirical surveys consistently find that the vast majority of respondents, including those who are poor or disabled, consider themselves fairly happy.

- When asked to rate their happiness, only a small minority of people place themselves below the neutral point on happiness scales.

- Aggregate data from nearly 1000 surveys indicate that national happiness scores tend to cluster towards the positive end of the scale.

- National happiness scores have generally been on the rise since the 1980s, suggesting an overall improvement in subjective well-being over time.

- While there are significant disparities in subjective well-being among individuals, the overall trend indicates a more positive outlook on happiness than previously assumed.

What Isn’t Very Important?

Money:

- Money, while commonly believed to lead to greater happiness, has a surprisingly weak correlation with subjective well-being.

- Within specific nations, the correlation between income and happiness typically ranges from .12 to .20.

- Beyond a certain income threshold, usually around $75,000 in the United States, additional wealth doesn’t significantly increase happiness.

- Actual income doesn’t strongly correlate with people’s subjective perceptions of whether they have enough money to meet their needs.

- Rising income often leads to escalating material desires, contributing to dissatisfaction when those desires can’t be fulfilled.

- People who emphasize the pursuit of wealth and materialistic goals tend to be somewhat less happy than others, possibly due to less satisfaction from non-financial aspects of life.

- Higher income is associated with working longer hours and allocating fewer hours to leisure pursuits.

- Wealthy individuals may become jaded, undermining their ability to savor positive experiences.

Age:

- Age has generally been found to have no significant relationship with global estimates of happiness according to studies by Lykken (1999) and Myers & Diener (1997).

- A study involving over 7,000 adults concluded that happiness levels do not vary with age (Cooper et al., 2011).

- However, recent research, such as a Gallup telephone poll of over 340,000 people, revealed a U-shaped relationship between age and happiness (Stone et al., 2010).

- Happiness tends to be relatively high in people’s 20s and 30s, dips in their 40s and 50s, then steadily climbs in their 60s and 70s.

- These findings suggest that conclusions about the relationship between age and happiness may need revision, although more research is necessary.

Gender:

- Women are treated for depressive disorders about twice as often as men, suggesting a potential gender difference in mental health.

- Despite this, research by Lykken (1999) indicates that men tend to have better jobs and higher pay, yet they report well-being levels similar to those of women.

- Surprisingly, gender accounts for less than 1% of the variation in people’s subjective well-being according to Myers (1992).

- This suggests that while there may be disparities in mental health treatment and job opportunities between genders, these factors have minimal impact on overall subjective well-being.

Parenthood:

- Parenthood brings both joy and fulfillment, as well as headaches and hassles, making it a complex experience.

- Compared to childless couples, parents tend to worry more and experience more marital problems.

- Despite the challenges, evidence suggests that the positive and negative aspects of parenthood balance each other out.

- Research by Argyle (2001) indicates that people who have children are neither more nor less happy than those without children.

- This suggests that while parenthood may bring both joys and stresses, its overall impact on happiness appears to be neutral.

Intelligence:

- Despite being highly valued in society, there is no found association between IQ scores and happiness according to research by Diener, Kesebir, & Tov (2009).

- Similarly, educational attainment does not appear to be related to life satisfaction, as suggested by research conducted by Ross & Van Willigen (1997).

- This indicates that while intelligence and education are esteemed in society, they do not necessarily correlate with overall happiness or life satisfaction.

- Other factors beyond intellectual abilities and education likely play a more significant role in determining subjective well-being.

Physical attractiveness:

- Despite the advantages that good-looking individuals enjoy in society, such as social and professional opportunities, the correlation between physical attractiveness and happiness is negligible.

- Research conducted by Diener, Wolsic, & Fujita (1995) indicates that there is no significant association between attractiveness and happiness.

- Despite being considered an important resource in Western society, physical attractiveness does not appear to have a substantial impact on overall happiness levels.

- Other factors beyond physical appearance likely play a more significant role in determining an individual’s subjective well-being.

What Is Somewhat Important?

Health:

- While good physical health might be assumed to be essential for happiness, individuals tend to adapt to health problems.

- Research, such as that by Riis et al. (2005), indicates that individuals with serious, disabling health conditions are not as unhappy as expected.

- Good health alone may not lead to happiness because people often take good health for granted.

- Despite this, there is a moderate positive correlation (average = .32) between health status and subjective well-being, as found in research by Argyle (1999).

- Additionally, happiness may contribute to better health, as evidenced by research showing a positive correlation between happiness and longevity, as noted by Veenhoven (2008).

- This suggests a reciprocal relationship between happiness and health, where good health can promote happiness to some extent, and happiness may also contribute to better health outcomes.

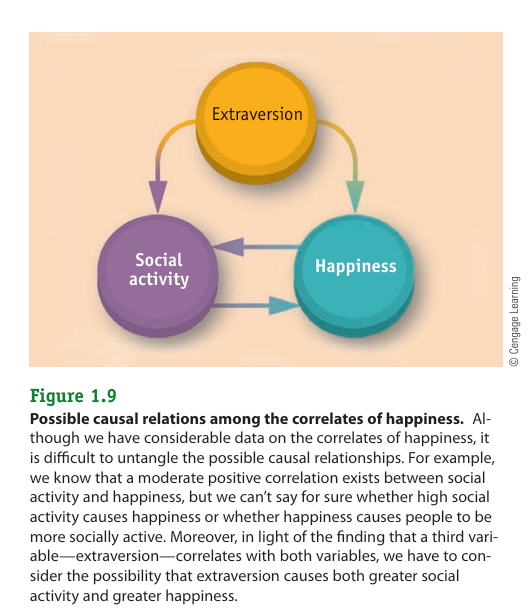

Social Activity:

- Satisfaction with interpersonal relationships contributes to individuals’ happiness, reflecting humans’ social nature.

- Research by Diener & Seligman (2004) indicates that people who are satisfied with their friendship networks and are socially active tend to report above-average levels of happiness.

- Exceptionally happy individuals often report greater satisfaction with their social relations compared to others, according to Diener & Seligman (2002).

- A recent study by Mehl et al. (2010) found that individuals who engaged in more deep, substantive conversations reported higher levels of happiness compared to those who mainly engaged in small talk.

- This suggests that the quality of social interactions, particularly engaging in deep conversations, is associated with greater happiness.

- Richer social networks are likely to facilitate more meaningful conversations, contributing to overall happiness levels.

Religion:

- The link between religiosity and subjective well-being is modest, but surveys suggest that individuals with sincere religious beliefs are more likely to be happy than those who identify as nonreligious, according to Myers (2008).

- The association between religion and happiness appears to be stronger in societies facing difficult and stressful circumstances.

- Conversely, in more affluent societies where circumstances are less threatening, the link between religion and happiness tends to be weaker, as noted by Diener, Tay, & Myers (2011).

- These findings imply that religion may serve as a coping mechanism for individuals facing adversity.

- The observed trend of declining religious affiliation in affluent countries may be attributed to lower overall adversity levels, as religion’s role in coping becomes less essential.

Culture:

- Surveys indicate moderate differences in mean levels of subjective well-being among nations, with happier populations generally found in affluent countries and less happy populations in poorer nations, as observed by Diener, Kesebir, & Tov (2009).

- While wealth is a weak predictor of subjective well-being within cultures, comparisons between cultures reveal strong correlations between nations’ wealth and their people’s average happiness, according to Tov & Diener (2007).

- The paradox of national wealth and happiness disparities is explained by theorists who argue that national wealth serves as a marker associated with various cultural conditions influencing happiness.

- Nations’ economic development correlates with factors such as greater recognition of human rights, income equality, gender equality, and democratic governance, as highlighted by Tov & Diener (2007).

- Therefore, it’s not solely affluence but the broader matrix of cultural conditions associated with economic development that drives disparities in subjective well-being among cultures.

- Income inequality has been linked to reduced happiness, further supporting the idea that broader cultural factors play a significant role in shaping subjective well-being, as shown in the study by Oishi, Kesebir, & Diener (2011).

What Is Very Important?

Love, Marriage And Relationship Satisfaction:

- Romantic relationships, despite their potential for stress, are consistently rated as one of the most critical ingredients for happiness, according to Myers (1999).

- Marital status is a key correlate of happiness, with married individuals generally reporting higher levels of happiness compared to single or divorced individuals, as found by Myers & Diener (1995).

- This disparity in happiness between married and unmarried individuals holds true across various cultures, suggesting a universal trend, as indicated by Diener et al. (2000).

- Marital satisfaction predicts personal well-being among married individuals, highlighting the importance of relationship quality for happiness, according to Proulx, Helms, & Buehler (2007).

- While marital status is often used as a marker of relationship satisfaction, it’s likely that relationship satisfaction itself fosters happiness, implying that one doesn’t necessarily need to be married to be happy.

- Both married and cohabiting individuals tend to be happier than those who remain single, suggesting that relationship satisfaction, regardless of marital status, contributes significantly to happiness, as evidenced by a study by Musick & Bumpass (2012).

Work:

- Despite common complaints about jobs, work is a significant source of happiness, with job satisfaction strongly associated with overall happiness, according to research by Judge & Klinger (2008).

- While relationship satisfaction may be more critical, job satisfaction still plays a substantial role in determining general happiness levels.

- Studies indicate that unemployment has strong negative effects on subjective well-being, highlighting the importance of employment for happiness, as demonstrated by research conducted by Lucas et al. (2004).

- It’s challenging to determine whether job satisfaction causes happiness or vice versa, but evidence suggests that causation flows both ways.

- In other words, individuals with higher job satisfaction tend to report greater overall happiness, and happier individuals may also perceive their jobs more positively.

- This reciprocal relationship between job satisfaction and happiness underscores the significance of work in influencing subjective well-being.

Genetics and Personality:

- The best predictor of individuals’ future happiness is their past happiness, indicating a strong influence of genetics and personality traits, as found by Lucas & Diener (2008).

- Some individuals appear predisposed to be happy or unhappy regardless of external circumstances, suggesting a significant role of genetics and personality in shaping happiness.

- A study by Brickman, Coates, & Janoff-Bulman (1978) found only modest differences in overall happiness between recent lottery winners and recent accident victims who became quadriplegics, highlighting the limited influence of life events on happiness.

- This study surprised investigators, demonstrating that extremely fortuitous or tragic events did not have a dramatic impact on individuals’ happiness levels.

- Several lines of evidence suggest that happiness is not solely dependent on external circumstances, such as acquiring material possessions or achieving career success, but rather on internal factors, such as one’s outlook on life, as suggested by Lyubomirsky, Sheldon, & Schkade (2005).

- Internal factors, such as personality traits and mindset, play a significant role in determining an individual’s happiness, often outweighing the influence of external events or circumstances.

- Studies suggest that a substantial portion of the variance in happiness can be attributed to people’s genetic predispositions, potentially accounting for as much as 50%, according to Lyubomirsky et al. (2005).

- Genes may influence happiness by shaping an individual’s temperament and personality, both of which are highly heritable traits.

- Researchers have started to explore links between personality traits and subjective well-being, uncovering relatively strong correlations, as shown by Steel, Schmidt, & Schultz (2008).

- Extraversion, characterized by being outgoing, upbeat, and sociable, is one of the better predictors of happiness, with extraverted individuals generally reporting higher levels of happiness.

- Neuroticism, which encompasses traits like anxiety, hostility, insecurity, and self-consciousness, is another potent predictor of happiness, with individuals high in neuroticism tending to be less happy than others.

- Personality traits such as extraversion and neuroticism may influence happiness by shaping how individuals recall and evaluate their personal experiences, as suggested by Zhang & Howell (2011).

- Extraverts often view their lives through a positive lens, making positive evaluations with few regrets, while those high in neuroticism tend to evaluate their experiences with a more negative slant.

Conclusions

- Subjective well-being is influenced more by subjective feelings rather than objective realities like health, wealth, job, or age.

- Relative comparison plays a significant role in evaluating happiness; people assess what they have in comparison to those around them, especially in terms of wealth and social status.

- There’s a surprising discrepancy between what people think will make them happy and what actually does. Affective forecasting, or predicting emotional reactions to future events, often leads to inaccurate estimations of pleasure or misery.

- Hedonic adaptation refers to the tendency for individuals to adjust their baseline for happiness or satisfaction, leading to a lack of sustained increase in happiness despite improvements in circumstances, such as income.

- This adaptation effect can create a “hedonic treadmill,” where despite positive changes, individuals find themselves no happier due to their shifting baseline.

- Conversely, hedonic adaptation may help individuals cope with major setbacks or challenges by adjusting their perception of the situation and finding new ways to evaluate events.

- For instance, individuals facing significant adversity like imprisonment or debilitating illness may adapt to their circumstances over time, leading to a level of happiness or contentment that might be unexpected.

- While hedonic adaptation doesn’t completely negate the impact of life’s difficulties, it suggests that people are often more resilient and adaptable than commonly believed.

- Psychological research can offer insights into practical challenges, such as achieving success as a student, by applying findings to everyday problems.

IMPROVING ACADEMIC PERFORMANCE

- Many students lack essential study skills and habits upon entering college, which can hinder their academic success.

- The U.S. educational system often lacks formal instruction on effective study techniques, contributing to students’ poor study habits.

- Psychology offers valuable insights into improving academic performance by providing guidance on developing better study habits.

- Key areas for improvement include promoting effective study habits, enhancing reading strategies, maximizing learning from lectures, and improving memory retention.

- Addressing these deficiencies can help students achieve better academic outcomes and succeed in their college endeavors.

Developing Sound Study Habits

- Academic performance in college is commonly assumed to be primarily determined by students’ intelligence or general mental ability.

- College admissions tests like the SAT and ACT, which assess general cognitive ability, often predict college grades effectively.

- However, research indicates that measures of study skills, habits, and attitudes also strongly predict college grades.

- A large-scale review by Crede and Kuncel (2008) found that study skills and habits predict college grades nearly as well as admissions tests do.

- This review suggests that study habits are significantly influential in determining college success, sometimes comparable to innate ability.

- Many students underestimate the importance of their study skills, focusing more on innate intelligence.

- While mental ability may be challenging to increase significantly, study habits can typically be enhanced considerably with effort.

- Effective study habits often involve acknowledging that studying requires hard work and setting up an organized program to promote adequate study.

- According to Siebert and Karr (2008), such a program should consider various factors to enhance study habits effectively.

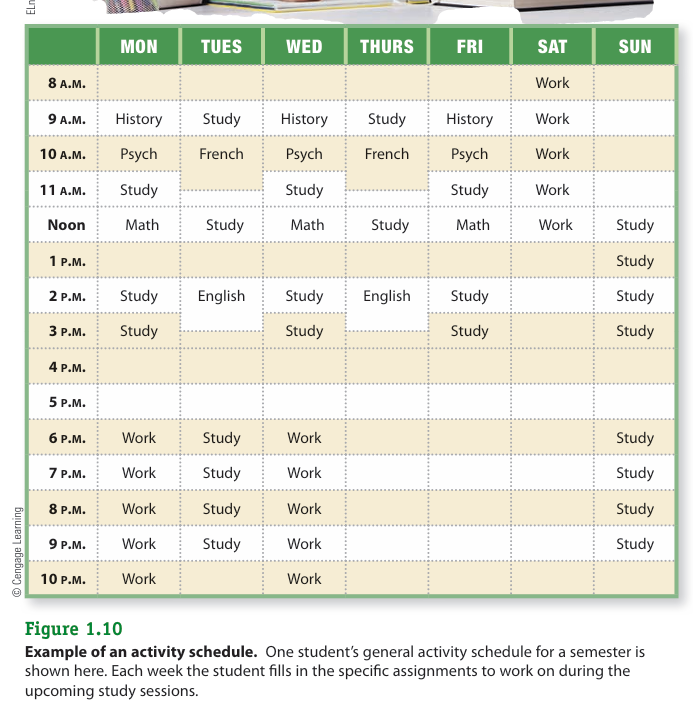

Set up a schedule for studying

- Successful college students demonstrate effective time management by monitoring and regulating their study time.

- Waiting for the urge to study may lead to procrastination and insufficient preparation by the time exams arrive.

- Allocate specific times for studying by considering your existing commitments like work and housekeeping.

- Schedule study sessions when you are most alert and consider your limits for sustained focus to prevent fatigue.

- Incorporate study breaks into your schedule to maintain concentration and prevent burnout.

- Writing down your study schedule serves as a reminder and increases commitment to the plan.

- Start by creating a general schedule for the quarter or semester and then plan specific assignments for each study session weekly.

- Avoid cramming for exams as it is often ineffective and can strain memorization capabilities, energy levels, and increase test anxiety.

- Proactively plan for major tasks like term papers and reports to avoid the tendency to prioritize simpler tasks and procrastinate on larger assignments.

- Break down major assignments into smaller tasks and schedule them individually to ensure timely completion and thoroughness.

Find a place to study where you can concentrate

- The environment where you choose to study plays a crucial role in your effectiveness.

- Minimize distractions by selecting a study location where interruptions are less likely to occur.

- Avoid studying in places where distractions like television, loud music, or conversations are prevalent.

- Relying solely on willpower to overcome distractions is often ineffective.

- Instead, plan ahead and proactively avoid distractions by choosing a conducive study environment.

- Planning ahead helps to mitigate the temptation of distractions and enhances focus and productivity during study sessions.

Reward your studying:

- Motivating oneself to study regularly can be challenging due to the distant payoff associated with academic achievements.

- Long-term rewards like a degree or even short-term rewards such as earning an A in a course may seem distant and abstract.

- To address this issue, it’s beneficial to provide oneself with immediate rewards for studying.

- Offering tangible rewards such as a snack, watching a TV show, or calling a friend after completing a study session can increase motivation.

- Setting realistic study goals and rewarding oneself upon their completion helps reinforce positive study habits and maintain motivation over time.

Improving Your Reading

- Improve reading comprehension by previewing reading assignments section by section.

- Actively process the meaning of the information while reading.

- Strive to identify the key ideas of each paragraph to enhance comprehension.

- Carefully review these key ideas after completing each section of reading.

- Utilize learning aids provided in modern textbooks such as chapter outlines, summaries, and learning objectives.

- Take advantage of textbook learning aids to recognize important points within chapters.

- Consider whether and how to mark up reading assignments effectively.

- Avoid simply running a marker through text without thoughtful selectivity, as it can be counterproductive.

- Research suggests that highlighting textbooks can be a useful strategy if done effectively and followed by review.

- Effective highlighting fosters active reading, improves comprehension, and reduces the need for extensive review.

- Focus on identifying and highlighting main ideas, key supporting details, and technical terms.

- Strive to condense the material to a manageable size by highlighting judiciously.

- Utilize retrieval practice by reading a section of text, setting it aside, and attempting to recall as much information as possible.

- Review the material and repeat the recall effort to reinforce learning.

- Retrieval practice has been found to be superior to simple repeated study and elaborate concept-mapping procedures for enhancing learning.

- Another effective method is to read a passage, set it aside, and generate questions about the content.

- Attempt to answer the questions, which helps reinforce understanding and retention of the material.

- This strategy has been shown to result in greater mastery of material compared to simply reading and rereading sections of text.

- Both retrieval practice and generating questions actively engage the learner and promote deeper understanding and retention of the material.

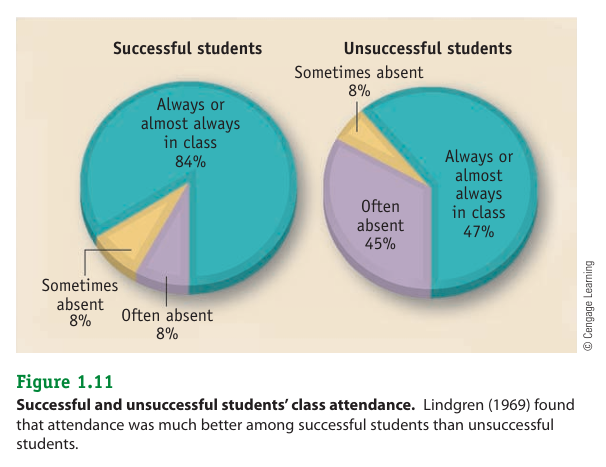

Getting More out of Lectures

- Poor class attendance is correlated with lower grades, highlighting the importance of attending lectures regularly.

- Even if lectures are challenging or uninteresting, attending class provides insight into the instructor’s thought process, which can aid in exam preparation.

- Attentive note-taking during lectures is associated with improved learning and academic performance.

- Many students’ lecture notes are incomplete, capturing less than 40% of crucial ideas, emphasizing the need for thorough note-taking.

- Staying motivated, attentive, and putting effort into comprehensive note-taking is key to maximizing learning from lectures.

- Active listening procedures enhance engagement during lectures, promoting deeper understanding.

- Preparing for lectures by reading ahead in the textbook reduces the amount of new information to digest during class.

- Translating lectures into your own words aids in organizing and comprehending the material.

- Look for cues from the instructor about important points or concepts, such as repetition or explicit statements.

- Asking questions during lectures fosters active engagement and provides clarification on misunderstood points, a practice often welcomed by professors.

Applying Memory Principles

Engage in Adequate Practice

- Scientific investigation of memory processes traces back to 1885 with Hermann Ebbinghaus’s pioneering studies.

- Psychologists have uncovered principles about memory relevant to improving study skills.

- Adequate practice, rather than guaranteeing perfection, leads to improved retention.

- Repeatedly reviewing information enhances retention, with studies showing that retention improves with increased rehearsal.

- Overlearning, continued rehearsal of material after mastery, has been found to enhance retention.

- Krueger’s classic study demonstrated that overlearning led to better recall of memorized lists, even after participants recited the list without error.

- Modern studies support the benefits of overlearning, showing enhanced performance on exams occurring within a week.

- However, evidence on the long-term benefits of overlearning, such as months later, is inconsistent.

- Despite the well-known benefits of practice, people tend to overestimate their knowledge of a topic and their performance on subsequent memory tests.

- Additionally, individuals often underestimate the value of additional study and practice after initial exposure to material.

- Informally testing oneself on mastered information before a real test is advisable to gauge mastery and enhance retention.

- Recent research highlights the testing effect, where taking a test on material improves performance on subsequent tests more than studying for an equal amount of time.

- The testing effect is further enhanced when participants receive feedback on their test performance.

- Laboratory findings on the testing effect have been replicated in real-world educational settings.

- However, relatively few students are aware of the value of testing, despite its efficacy in improving retention.

- Testing is beneficial because it forces students to engage in effortful retrieval of information, which promotes future retention.

- Even unsuccessful retrieval efforts have been shown to enhance retention, highlighting the effectiveness of self-testing as a memory tool.

- Given its effectiveness, it is advisable to utilize practice tests, such as those provided in textbooks or online, to enhance learning and retention.

Use Distributed Practice

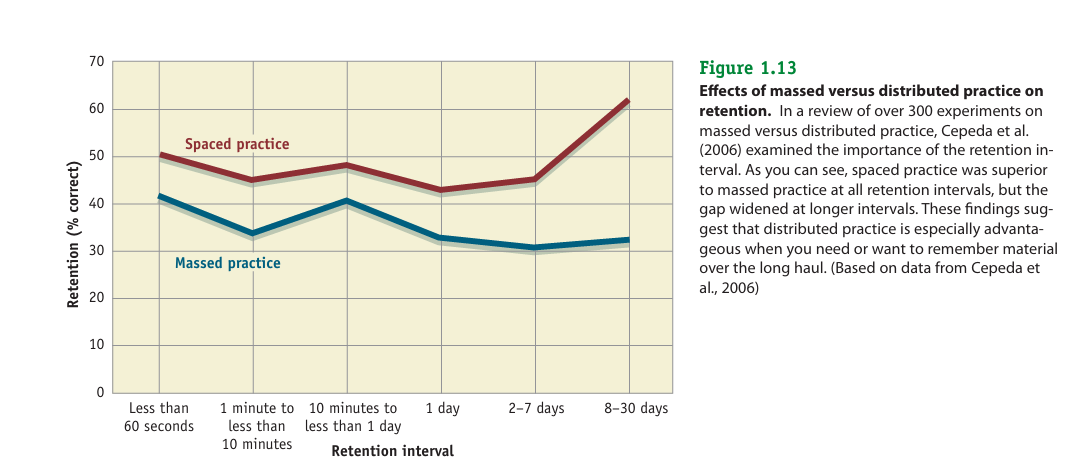

- Evidence suggests that retention is greater after distributed practice compared to massed practice.

- Distributed practice involves spreading study sessions over multiple days, while massed practice involves cramming all study into one continuous period.

- A review of over 300 experiments showed that the longer the retention interval between studying and testing, the larger the advantage for spaced practice.

- The longer the retention interval, the longer the optimal “break” between practice trials.

- When an upcoming test is more than two days away, the optimal interval between practice periods appears to be around 24 hours.

- The superiority of distributed practice over massed practice highlights the inefficacy of cramming for studying exams.

Organize Information

- Retention of information is typically greater when it is well organized.

- Hierarchical organization, especially when applicable, is particularly helpful for enhancing retention.

- Outlining reading assignments for school can be a beneficial practice to organize information effectively.

- Empirical evidence suggests that outlining material from textbooks can enhance retention of the material.

- Studies, such as by McDaniel, Waddill, and Shakesby (1996), support the notion that outlining material can improve retention.

Emphasize Deep Processing

- Depth of processing is crucial for memory retention, emphasizing the significance of engaging meaningfully with material (Craik & Tulving, 1975).

- Merely going over material repeatedly may not be as effective as deeply analyzing its meaning (Craik & Tulving, 1975).

- Wrestling fully with the meaning of what you read is essential for remembering it (Einstein & McDaniel, 2004).

- Students may benefit more from focusing on understanding and analyzing their reading assignments rather than relying solely on rote repetition.

- Making material personally meaningful can enhance learning outcomes.

- Relating information to one’s own life and experiences can aid in understanding and retention.

- For instance, in psychology, connecting concepts like assertiveness to real-life examples can deepen comprehension and retention.

- Reflecting on assertive individuals in one’s life and analyzing the reasons behind their behavior can facilitate a deeper understanding of the concept.

Use Mnemonic Devices

- Making abstract material personally meaningful can be challenging, such as relating to polymers in chemistry.

- To address this challenge, mnemonic devices have been developed as strategies for enhancing memory.

- Mnemonic devices aim to make abstract material more relatable and meaningful by providing memorable associations or cues.

- These devices can include acronyms, visual imagery, rhymes, or other creative techniques to aid in memory retention.

- By employing mnemonic devices, learners can transform complex or abstract concepts into more accessible and memorable forms.

- Mnemonic strategies offer alternative pathways for encoding information, allowing for easier recall and understanding of difficult subjects like chemistry.

Acrostics and acronyms

- Acrostics use phrases or poems where the initial letters of each word or line serve as cues to recall abstract words or concepts.

- An example is remembering the order of musical notes with the phrase “Every good boy does fine” or “deserves favor”.

- Acronyms are words formed by taking the initial letters of a series of words.

- For instance, “Roy G. Biv” is a commonly used acronym to remember the colors of the light spectrum: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet.

- Acrostics and acronyms serve as effective memory tools, particularly when individuals create them for themselves.

- These mnemonic devices provide memorable cues that aid in the retention and recall of information (Hermann, Raybeck, & Gruneberg, 2002).

Link method

- The link method involves creating mental images that connect items to be remembered.

- For example, if you need to remember to pick up a news magazine, shaving cream, film, and pens from the drugstore, you might visualize a scenario where a public figure from the magazine is shaving with a pen while being photographed.

- The key is to create vivid and imaginative mental images that link the items together in a memorable way.

- Some researchers propose that the more bizarre or unusual the images, the more effectively they will be remembered (Iaccino, 1996).

- By associating mundane items with unexpected or outlandish scenarios, the brain is more likely to encode and retain the information for later recall.

- The link method leverages the brain’s natural ability to remember visual and spatial relationships, enhancing memory retention through imaginative associations.

Method of Loci

- The method of loci involves mentally walking along a familiar path while associating images of items to remember with specific locations along that path.

- Initially, you commit to memory a series of loci, which are specific places along the chosen pathway, typically in your home or neighborhood.

- Each item you want to remember is then envisioned in connection with one of these locations, creating distinctive and vivid mental images.

- When you need to recall the items, you mentally retrace your path, with each location serving as a retrieval cue for the associated image.

- This method ensures that items are remembered in their correct order, as the sequence of locations determines the order of recall.

- Empirical studies have supported the effectiveness of the method of loci for memorizing lists (Massen & Vaterrodt-Plünnecke, 2006).

- Research suggests that using loci along a pathway from home to work is more effective than a pathway solely within one’s home for memory retention (Massen et al., 2009).

- The method of loci capitalizes on spatial memory and the brain’s ability to recall visual and spatial relationships, providing a powerful mnemonic technique for enhancing memory performance.