APPROACHES TO POWER AND POLITICS

Part – I

Chapter 1. Marxist Approaches to Power

- Marxist analysis focuses on power relations as manifestations of specific class domination.

- Power and resistance are viewed in relation to the reproduction or transformation of class domination.

- Class domination doesn’t exclusively involve actors with clear class identities; other factors are considered but seen in relation to class domination.

- Marxists emphasize the links among economic, political, and ideological class domination, leading to theoretical and empirical disagreements.

- Bases of class power are located in social relations of production, control over the state, or intellectual hegemony, varying among Marxist approaches.

- Marxists highlight the limitations of power rooted in class domination, attributing fragility and instability to structural contradictions.

- All forms of social power linked to class domination are considered inherently fragile, provisional, and temporary, requiring ongoing struggles.

- Marxists address questions of strategy and tactics, analyzing empirical strategies to reproduce, resist, or overthrow class domination.

- Political debates involve discussions on appropriate identities, interests, strategies, and tactics for dominated classes and oppressed groups.

- Strategic analysis considers spatio-temporal dimensions, reflecting growing theoretical interest in questions of temporality and socio-spatiality.

Power as a Social Relation

- Marxists view power as capacities, not just their actualization.

- Capacities are socially structured, not randomly dispersed among individuals.

- Focus on capacities grounded in structured social relations, not individual properties in isolation.

- Structured social relations entail reciprocal, often asymmetrical, capacities and vulnerabilities.

- Hegel’s master–slave dialectic and Marx’s capital–labour interdependence exemplify enduring, reproduced, reciprocal practices.

- Power involves securing the continuity of social relations rather than producing radical change.

- Social relations of power involve both parties engaging in their ordinary activities.

- Capitalist wage relation illustrates how a formally free exchange leads to workplace despotism and economic exploitation.

- Working-class resistance indicates that the successful exercise of power is contingent on specific actions in specific circumstances.

- Marxists see power as contingent, with no general or guaranteed power – only particular powers and specific exercises in particular contexts.

General Remarks on Class Domination

- Marxism focuses on class domination as its primary interest in analyzing power.

- Weberian analyses consider various forms of domination, including status and party, not solely economic class.

- Radical feminists prioritize patriarchy and its effects on power dynamics.

- Marxists view class powers as dispersed throughout society, investigating both economic and non-economic class domination.

- Class domination extends beyond the labor process to the wider economic and ideological spheres.

- Some Marxists link political and ideological domination directly to economic domination, while others emphasize complex relations among the three.

- Marxists recognize the primary role of politics in practice, especially through political revolution.

- The state is central to Marxist analyses, responsible for maintaining structural integration and social cohesion in a society divided into classes.

- The state’s role is crucial for preventing revolutionary crises and avoiding the mutual ruin of contending classes in capitalism.

Economic Class Domination

- Marxism is based on the existence of antagonistic modes of production throughout human history.

- A mode of production combines forces of production (materials, means, technical labor) and social relations of production.

- Productive forces and social relations shape a society’s choice and deployment of available resources.

- Social relations include control over resource allocation, social division of labor, and class relations based on property ownership and economic exploitation.

- Some Marxists emphasize labor process organization as the primary site of capitalist-worker antagonism.

- Control over the labor process is crucial for capital valorization, with various forms like bureaucratic, technical, and despotic control.

- Others study the overall organization of production and its connection to capital circuits, emphasizing factors like industrial vs. financial capital, globalization, and labor market flexibility.

- Different economic growth modes are associated with distinct power patterns; for example, Atlantic Fordism had a compromise between industrial capital and organized labor.

- Globalization and efforts to increase labor market flexibility, especially in neoliberal regimes (e.g., Reaganism, Thatcherism), contributed to declining labor share, financialization, and the 2007-2009 global financial crisis.

- Neoliberal shifts led to a divorce between financial and industrial capital, impacting patterns of class domination.

Political Class Domination

- Marxist accounts of political class domination start with the state’s role in securing conditions for economic class domination.

- The state compensates for market failures, organizes collective capitalist interests, and manages repercussions of economic exploitation.

- Marxists argue that institutional integration and social cohesion are necessary for rational economic calculation and capital accumulation.

- Three main Marxist approaches to the state: instrumentalist (neutral tool for political power), structuralist (inherently capitalist form), strategic-relational (social relation shaped by class struggle).

- Instrumentalists view the state as a tool for the ruling capitalist class to dominate society.

- Structuralists argue that the state’s structure inherently organizes capital and disorganizes the working class.

- Strategic-relational theorists, like Poulantzas, see the state as a social relation shaped by changing balances of forces and strategies.

- The state is class-biased, not class-neutral, due to structural selectivity in institutions, capacities, and resources.

- The capitalist state’s powers are activated through politicians and officials in specific contexts, leading to contradictions and class struggles.

- Political class struggle is continual, necessary for a capitalist power bloc to maintain unity and dominance over subaltern groups.

- Democratic transition to socialism requires disrupting the state’s strategic selectivity through mass struggle at a distance, within, and to transform the state.

Ideological Class Domination

- Marx’s “Ideology” (1845–1846) asserts that ruling ideas reflect the interests of the ruling class.

- Marxist perspectives on ideological class domination encompass commodity fetishism, citizenship, and struggles for influence in civil society.

- Interest in ideological class domination grows with the rise of democratic government, mass politics, and mass media in the late 19th and 20th centuries.

- Antonio Gramsci, an influential figure in this area, developed a distinct Marxist approach during his incarceration by the fascist regime.

- Gramsci sought to establish an autonomous Marxist science of politics, distinguishing different types of state and politics.

- He identified the state with its narrow sense as the politico-juridical apparatus, focusing on the mediation of political, intellectual, and moral leadership.

- Gramsci defined the state as “political society þ civil society,” emphasizing hegemony armored by coercion and active consent of the ruled.

- Force and hegemony are integral to state power, with force involving coercion and hegemony mobilizing active consent through leadership.

- Gramsci viewed the capitalist state as a mix of coercion, consent, fraud, and corruption, shaped by links to the economic system and civil society.

- In advanced capitalist democracies, Gramsci advocated a long-term war of position, developing a hegemonic collective will before a potential war of maneuver.

- While some see a parliamentary road to socialism, Gramsci emphasized the likelihood of a military-political resolution in a shorter, less bloody war of maneuver if hegemony is first achieved.

The Articulation of Economic, Political, and Ideological Domination

- Relations among economic, political, and ideological domination involve structurally inscribed selectivity and strategies that consolidate or undermine these selectivities.

- State bias is relative to specific strategies of specific forces advancing interests over time with specific sets of other forces.

- State forms (feudal vs. capitalist), regimes (democratic vs. despotic), and policy instruments (Keynesian vs. neoliberal) are essential to examine.

- Jessop, influenced by Poulantzas, emphasizes the structural moment of “strategic selectivity,” while Gramsci focuses on its strategic moment.

- Gramsci rejects the orthodox Marxist view of a unilateral determination of the superstructure by the economic base.

- He argues for a reciprocal relationship between the economic base and its politico-ideological superstructure, secured through specific practices.

- Ethico-political practices co-constitute economic structures, providing them with rationale and legitimacy.

- The concept of an “historical bloc” denotes the reciprocal relationship between base and superstructure.

- Gramsci introduces power bloc and hegemonic bloc to analyze alliances among dominant classes and broader national-popular forces.

- A hegemonic bloc is a durable alliance organized by a class capable of exercising leadership over both dominant classes and popular masses.

- Organic intellectuals play a key organizational role in developing hegemonic projects expressing the long-term interests of dominant or subaltern classes.

- Durable hegemony depends on a decisive economic nucleus, and Gramsci criticizes efforts to build an arbitrary, rationalistic hegemony ignoring economic realities.

Spatio-Temporal Moments of Domination

- Time and space are interconnected and impact economic, political, and ideological domination.

- Marx’s analysis of capital accumulation highlights the political economy of time and inherent tendencies for spatial expansion.

- Capital accumulation involves competition to reduce socially necessary labor time, turnover time, and reproduction time of nature.

- Spatio-temporal dynamics influence forms of political domination, challenging state sovereignty in both territorial and temporal dimensions.

- Acceleration of economic rhythms relative to the state’s leads to conflicts between market and state times.

- States respond with laissez-faire, temporal compression, or attempts to decelerate fast capitalism.

- Temporal compression may result in fast policy, favoring executive dominance, finance over industrial capital, and consumption over investment.

- Fast policy undermines democratic processes, corporatism, and the rule of law, concentrating power in the executive.

- Relative political time can be created by slowing capital circuits, such as through a Tobin tax on financial transactions.

- Climate change becomes a field of struggle with conflicts between states and vested interests in economic expansion.

- Changing spatio-temporalities increase complexity in economic, political, and ideological relations on a global scale.

- Lack of a world state or effective global governance undermines state capacities, leading to a shift from government to governance.

- Multi-spatial governance responds to spatio-temporal challenges, impacting the configuration of class power.

Conclusions

- Marxist approaches to power focus on themes including power and class domination, mediations among economic, political, and ideological domination, limitations and contradictions grounded in capitalism’s social relations, and the role of strategy and tactics.

- Class domination is privileged, marginalizing other forms of social domination such as patriarchal, ethnic, racial, and interstate.

- Marxist analyses may exaggerate the structural coherence of class domination, overlooking disjunctures, contradictions, and countervailing tendencies.

- Unified ruling class notions overlook the messiness and complexity of actual configurations of class power.

- Marxists risk overlooking sources of failure beyond class contradictions, reducing the limits of economic, political, and ideological power.

- Emphasis on strategy and tactics is important, avoiding the structuralist fallacy, but there’s a risk of voluntarism without considering specific conjunctures and broader structural contexts.

Chapter 2. Weber and Political Sociology

- Weber provides an existential account of political action, integrated into his political sociology.

- The account involves a dialectical movement between competition, struggle, and selection, and routine predictability.

- Weber’s definition of power and his typology of legitimate domination-rulership embody this dialectic.

- The dynamics of modern politics as business and vocation are understood through these concepts.

- Contrary to some claims, Weber’s view of direct democracy aligns unintentionally with democratic theorists who see genuine democracy in resistance to domination.

- Max Weber did not develop a systematic political sociology but addressed political themes throughout his work.

- He emphasized the primacy of politics over economic and social considerations in modernity.

- Weber argued that politics was where value commitments in other life spheres were contested.

- He saw sociology as crucial for revealing the forms of political struggle, social forces involved, and institutional structures at play.

- An unnoticed existential dialectic is embedded in Weber’s political sociology.

- Contemporary political sociologists have responded to Weber’s arguments and concerns.

- Weber’s political sociology includes the testing of political commitments against sociological and existential conditions, but this strand is undeveloped.

Weber’s Political Sociology

The dialectic of conflict and selection vs. methodical routine

- Weber’s political sociology is rooted in the ideal-typical concepts of power, legitimate domination, and the state.

- Social life, according to Weber, oscillates between purposively rational actions and actions driven by competition, conflict, and selection.

- The dialectic of conflict selection and institutional routinization shapes Weber’s political sociology at various levels.

- Conflict and selection are integral to Weber’s concepts of power (Macht) and legitimate domination (Herrschaft).

- Weber defines power as the probability of achieving one’s will over the resistance of others.

- Routinization of power, or Herrschaft, occurs when power is exercised predictably and without resistance.

- Politics, for Weber, involves the pursuit of power and domination, whether within states or between them.

- Weber’s definition of the state emphasizes its monopoly on legitimate physical violence within a specific territory.

- The struggle for power in politics involves seeking domination and control over the state’s resources.

- Weber’s typology of legitimate forms of domination includes charismatic, traditional, and rational-legal authority.

- Charismatic authority, rooted in unique personality, is the most unstable form and tends to routinize into traditional or rational-legal authority.

- The constant tension within each type of domination revolves around retaining loyalty from both staff and followers.

- Weber’s typology mirrors each other, demonstrating “elective affinities” and explaining the transition from one form of domination to another.

- Charismatic, traditional, and rational-legal authority both enable and constrain the political struggle for power.

- Weber’s political sociology provides a framework for understanding the dynamics and emergence of modern politics.

Politics as a ‘business’ and a ‘vocation’

- Weber explores the development of modern politics as an autonomous “enterprise” or “business” with its own professional requirements and organization.

- Five key political entities converge in modernity according to Weber’s analysis: political association, modern political party, modern parliament, modern state, and the leading or vocational politician.

- The legitimacy of the political community’s rule arises from its claim to provide protection against internal and external threats, establishing a monopoly of violence.

- The modern administrative state emerges from the political expropriation process, where political means are centralized under state authority, breaking away from traditional rulership.

- The political party evolves as a response to universal suffrage, becoming a bureaucratic machine to secure votes over a vast territory.

- Parliaments develop as arenas for political parties and potential testing grounds for the selection of new leading politicians.

- The leading politician is a professional and vocational figure, combining the demagogue, the prince, and the charismatic political leader.

- The emergence of the leading politician is not inevitable, and its development depends on a fortuitous combination of political character types.

- Weber emphasizes the sociological tenuousness of the leading politician figure, which develops only in the West through specific historical conditions.

- The convergence of these five developments produces an interlocking set of self-reproducing compulsory institutions, constituting politics as a modern business.

- The existential dialectic at work in political ethics involves leading politicians taking responsibility for both failed ends and the use of power and domination to achieve goals.

- While Weber defines the limits of political action within the logic of rational-legal and charismatic domination, he notes that the origin of modern politics lies in the logic of traditional domination.

- The ongoing struggle to expropriate political means, characteristic of traditional domination, is internalized within modern politics, leading to the repeated use of rational-legal and charismatic domination.

Weber’s political sociology and democracy

- Weber’s political sociology grapples with the conflict between modern liberal democracies and more direct forms of democracy.

- Some see Weber as a defender of liberal democracy, while others argue that his theory is in tension with this form.

- Weber’s defense of liberal democracy clashes with sociological conditions that do not necessarily favor this model.

- Democracy, even in its minimalist liberal form, faces challenges adapting to the logic of political struggle within the business side of politics.

- The struggle is influenced by the oscillation between charismatic forms of domination and rational-legal ones, often combined with traditional domination.

- Weber’s model of plebiscitary democracy endorses elections as a testing process to select political leaders with vocational qualities for executive office.

- Weber’s political sociology is insensitive to movements for popular self-rule and the extension of political equality into social rights.

- Weber does not distinguish genuine consent from mere acquiescence in his definition of legitimacy, making it challenging to accommodate direct forms of popular participation.

- Demands for popular will are seen by Weber as charismatic revolutionary moments opposed to all forms of domination, occasional and fleeting.

- Despite dismissing direct democratic political will as a durable form of legitimate rule, Weber acknowledges the characteristic of popular democratic involvement.

- Radical democratic theorists argue that active citizen-driven democracy resists institutionalization in routine forms of command and obedience.

- The democratic will, according to these theorists, does not constitute legitimate command unless citizens are also the subjects of their own laws.

- Demands for democracy beyond its liberal forms are seen by these theorists as caught in Weber’s dialectic of conflict and routinization, with alternative conclusions drawn regarding the acquiescence–consent distinction.

Weberian Political Sociology after Weber

- Recent Weberian political sociology has shifted focus from the existential tension in Weber’s work to two main directions.

- Michael Mann dissolves Weber’s dualistic concept of power and Herrschaft into four fluid sources of power: ideological, political, military, and economic.

- Randall Collins and Charles Tilly delve deeper into the role of military power in the formation of centralized states.

- Tilly identifies mechanisms undermining domination and rule, revealing limitations in Weber’s typology, especially in understanding protests and democratization.

- Present-day Weberian political sociology expands, revises, and criticizes Weber’s concepts, implicitly assessing political commitments and testing them against sociological conditions.

- Weber’s original goal of testing political commitments using political sociology is still awaiting explicit development in contemporary scholarship.

Chapter 3. Durkheim and Durkheimian Political Sociology

- Durkheim’s sociology addresses political sociology, focusing on concepts relevant to political institutions, the state, civil society, and cultural aspects.

- Fundamental conceptual building blocks include individualism (moral vs. egoistic), social solidarity, regulation (social and moral), intermediate associations, the state, collective effervescence, and symbolic representations of the socially sacred.

- Early accounts emphasized the evolution of the division of labor, but attention later shifted to politics, the state, and cultural symbolism.

- Durkheim viewed individual liberty as a central value but advocated for a moral individualism respecting societal needs.

- His critique of contemporary capitalism highlighted the lack of regulation and exacerbated inequalities.

- Durkheim’s political stance aligns with ethical socialism or guild socialism, emphasizing state reforms, including restricting inheritance and encouraging ethical regulation by intermediate institutions.

- His view of the state reflects a “communicative theory of politics,” emphasizing its role as a synthesizing intelligence for the whole society.

- Durkheim stressed the centrality of the individual person in modern thought, distinguishing between negative (pathological) and positive (balanced and progressive) forms of individualism.

- He opposed the dominance of economic thinking, advocating for a sociological perspective that prioritizes the social dimension and its moral basis.

- Recent Durkheimian sociology has made significant contributions within the ‘cultural turn,’ drawing inspiration from The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life and Durkheim’s discussion of binary structures in culture, influencing structuralism and symbolic approaches to politics.

Changing Views of Durkheimian Sociology

- Durkheim’s sociology faced delayed recognition in political sociology, attributed to his focus on developing sociology as an academic discipline and minimal direct involvement in politics.

- The delayed recognition could also be linked to the late publication and translation of his overtly political book, “Professional Ethics and Civic Morals,” 33 years after his death.

- Early American commentators tended to assimilate Durkheim’s thought into contemporary functionalist or voluntarist approaches, creating misleading dichotomies.

- Durkheim’s writings on politics, especially in “Professional Ethics and Civic Morals,” emphasized the need for social change to fulfill the ideals of the French Revolution.

- Unlike Marx, Durkheim rejected political revolution based on class conflict, foreseeing bureaucratic domination as an outcome.

- He analyzed the long-term evolutionary changes brought about by industrialization and identified the need for intermediate institutions to balance power and promote ethical regulation.

- Durkheim advocated for the development of modernized guild-like associations with economic and moral functions.

- His analysis in “Professional Ethics and Civic Morals” continued themes from “The Division of Labor in Society,” emphasizing the importance of solidary groups and group ethics for organic solidarity.

- Durkheim’s sociological perspective aimed to overcome the individualism vs. communitarianism dichotomy, focusing on social facts with characteristics of externality, constraint, and generality.

- During the 1960s-1980s, historical-comparative sociology largely overlooked Durkheim in favor of Marx and Weber, associating him with structural-functionalism.

- A shift occurred when sociologists recognized the relevance of Durkheimian concern for civil society structures and processes, particularly in intermediate domains of social life.

- Durkheim’s historical analyses, like “The Evolution of Educational Thought,” refuted criticisms regarding his understanding of ideology and education’s role in class interests.

- Durkheim’s ideas, notably from “The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life,” linked normative regulation of institutions with symbolic cultural logics, inspiring cultural sociologists to grant more autonomy to cultural factors in political analyses.

Cultural Sociology and Politics

- Disaffection with structural-functionalism in the 1970s led to a Durkheimian emphasis on symbolism, sacredness, and ritual in political sociology.

- Edward Shils emphasized symbolic “centres” in secular societies, allocating social status based on proximity to sacred sources.

- Clifford Geertz argued that cultural systems are “religious” based on sacralization, inspiring ritual devotion and group solidarity.

- Robert Bellah introduced the concept of “civil religions” in secular nations, relating political structures to a transcendent framework.

- Jeffrey Alexander traced theoretical continuities in Durkheimian sociology, applying the framework to political processes like the Watergate crisis.

- Alexander deconstructed binary symbolic structures in civil religion, analyzing the transition in public dramas of ritual cleansing.

- Philip Smith described the binary opposites of sacred and profane in liberal democracy, highlighting the characteristics associated with each.

- Durkheim’s vision of a pluralistic state involved intermediate associations mediating between the state and the individual.

- Ethnic nationalisms may challenge the equating of civil society with normal political processes, displaying particularistic and expressive characteristics.

- Durkheim’s wartime pamphlets countered German nationalist ideology, emphasizing the moral code rooted in universal rights.

- Jeffrey Alexander highlighted the analytical gap in Durkheim’s political sociology, particularly regarding how modern morality is connected to institutions.

- Neo-Durkheimians used Durkheim’s method to analyze symbolic binary codes in the wider civil sphere, contributing to moral community and social solidarity.

- Alexander rejected utilitarian theories and rational choice approaches, emphasizing moral force as the basis of society.

- Alexander’s work, “The Civil Sphere,” provided a theoretical basis, while his analysis of the Obama presidential campaign exemplified empirical applications.

- Campaigning was described as an aesthetic activity, focusing on embodying and projecting qualities associated with the “discourse of liberty.”

- Durkheimian cultural sociology analyzes the cultural construction and meaning of social-political “facts” through symbolic representations and binary codes.

- Attention is given to the ways cultural codes interpret narratives about social inequalities and political qualities in our media-saturated age.

Chapter 4. Foucaultian Analysis of Power, Government, Politics

- Foucault’s nominalist understanding of power cautions against reification, emphasizing the total structure of actions on behavior.

- Power relations are seen as ubiquitous in social life, and little value is attributed to discussing the nature of power in general.

- Dominance is a hierarchical relationship with a severe restriction of the subordinated parties’ margin of liberty.

- Foucault advocates resistance against domination, seeking conditions for power games with minimal domination.

- The government of a state, according to Foucault, involves actions aimed at influencing individuals to regulate their own behavior.

- Liberals see liberty as limiting government action, but Foucault presents it as an instrument of liberal government.

- Hindess suggests extending Foucault’s approach to dilemmas posed by politically oriented activity, international government, and authoritarian aspects of liberal government.

- Foucault challenges the reified view of power, emphasizing actions and causal relations over the possession of a power substance.

- Foucault’s normative critiques focus on resisting domination and challenging the political rationality underlying the modern state’s government.

- Foucault’s accounts of the emergence of government rationality in the early modern period and liberalism’s development inspire the governmentality school.

- Academic work on governmentality studies government in the modern West, considering liberalism as a specific form of governmental reason.

- Foucault’s treatment of government needs adaptation for politically oriented action, international government, and authoritarian aspects of liberal political reason.

Government

- The term ‘government’ in contemporary political analysis can refer to the supreme authority in states or denote a kind of activity.

- Aristotle distinguishes various forms of government, including the government of a wife and children and the self-rule of an individual.

- Foucault notes continuity between different forms of government, emphasizing their shared concern for affecting the conduct of the governed.

- Government involves indirect action on the actions of others, influencing how individuals regulate their own behavior.

- Distinction between government and domination: government allows a certain margin of liberty for the governed in regulating their behavior.

- The modern art of government aims to conduct the affairs of the population in the interests of the whole, extending beyond the institutions of the state.

- Foucault discusses liberalism as a rationality of government, challenging conventional political theory’s view of individual liberty.

- Liberalism in governmentality focuses on using individual capacity for autonomous, self-directed activity to benefit the state.

- Liberal government aims to establish conditions for various domains of free interaction to operate effectively with minimal state interference.

- Effective liberal government relies on reliable knowledge provided by economics and social sciences about the processes and conditions sustaining free interaction.

- Governmentality scholars analyze neoliberal attempts to govern through individual choice, personal empowerment, and market regimes.

- Individual liberty in neoliberal government is not just a limit but a means of governing, relying on the regulation of conduct by the state and others.

- Neoliberal government depends on the expertise of various professionals, from psychiatrists to economists, to shape individuals’ conduct in line with market models.

Politics and Government

- Foucault’s analysis of the government of the state contributes to understanding a specific kind of politics, focusing on governing the population in the interests of the whole.

- Terms like ‘politics’ often refer to the government of the state, aligning with Foucault’s usage and the governmentality literature.

- The critique of political reason in Foucault’s Tanner Lectures targets the rationality of the government of the state.

- Foucault distinguishes political government from other forms of government, emphasizing its focus on the state.

- Foucault’s analysis of government, particularly liberal and neoliberal forms, sheds light on contemporary politics aiming to govern through the promotion of certain freedoms.

- The literature explores how governmental politics utilizes practices of individual self-government and elements of civil society.

- However, the analysis of government falls short in addressing politically oriented activity, government in the international system, and authoritarian aspects of liberal government.

Government and Partisan Politics

- Weber defines politically oriented action as aiming to influence the government of a political organization, particularly in power appropriation, redistribution, or allocation.

- Unlike Foucault’s focus on overall state interests, Weber’s politically oriented action emphasizes partisan activities of parties, pressure groups, social movements, and individuals within them.

- Politically oriented activity may be motivated by religious doctrine, issues of the Prince, or conflicting views on the principles intrinsic to state government.

- Foucault’s treatment of government overlooks the governmental implications of politically oriented activity, limiting its analysis.

- Partisanship is inherent in the classical view of government’s purpose, providing fertile ground for partisan politics, especially in systems promoting individual freedom.

- Hume sees partisanship as an infection of government, with liberal and neoliberal rationalities also concerned with defending government purposes from partisan impact.

- Liberal and neoliberal strategies involve secrecy, misdirection, corporatization, and privatization to minimize inducements for partisan politics and limit partisan influence.

- Promotion of individual autonomy in these strategies inhibits political participation, while market interactions replace administrative apparatuses in governing individuals and organizations.

- The shift in government means is not a reduction in scope but a change in exercising power through market and quasi-market regimes.

- Neoliberal procedures, conducted by partisan politicians, provide opportunities for pursuing new forms of partisan advantage.

Government in the International Arena

- Foucault’s discussions of government deviate from the conventional view of the state as the ‘supreme authority.’

- However, they align conventionally by considering government as operating primarily within states.

- Conventional perspectives often depict relations between states as anarchic, regulated by treaties, informal agreements, and occasional wars.

- Foucault challenges this by proposing that the modern system of states functions as a regime of government with no central control.

- The international community is now considered the highest authority in certain political contexts.

- The modern art of government extends beyond governing individual state populations to encompass the larger population under the system of states.

- Two levels of international governance: promoting rule by territorial states and regulating the conduct of both states and their populations.

- The division of humanity into citizens of states and others is a form of government with powerful and often destructive effects.

- This division can lead to a denial of history and responsibility, influencing perceptions of responsibility for the conditions of less fortunate states.

- Governmental arrangements contribute to an exclusive sense of solidarity among citizens of individual states at the international level.

- Striking parallels exist between the contemporary international order and the late colonial liberal order.

- The late colonial order marked the global expansion of the European states system, with independence seen as a later stage in its globalization.

- Independence, while dismantling parts of imperial order, left other elements intact, expanding the membership of the states system.

- Independence introduced a new way of governing non-Western populations through their own states and the regulatory mechanisms of the overarching system.

- This reflects a modern version of late imperial indirect rule, utilizing markets and local states.

Liberal Authoritarianism

- Authoritarian rule has historically coexisted with liberal political reason in Western states.

- 19th-century Western states restricted freedom domestically and imposed rule forcefully abroad.

- Coercive practices persist in Western societies in criminal justice, policing, social services, and organizational management.

- In Latin America, Southeast Asia, and Eastern Europe, authoritarian rule has been used for economic liberalization.

- The governmentality literature often views coercive practices as external to liberal government.

- Nikolas Rose acknowledges liberal justifications for coercion but does not integrate them into his account of liberal government.

- Mitchell Dean suggests that governing through freedom may require alternative approaches for some individuals.

- The belief in individuals’ capacity for autonomous action shapes government practices.

- Liberals argue that underdeveloped capacities require constraints, as seen in John Stuart Mill’s views on colonial governance.

- Liberal political reason extends to subject peoples of imperial possessions and adults judged as incompetent.

- Authoritarian government in developmental contexts aims for eventual abolition, while in liberal states, it defends against partisan politics.

- Economic imperatives often justify restrictions on political freedom in societies with entrenched paternalistic attitudes.

Moving on

- Foucaultian studies focus on freedom, choice, and empowerment in contemporary Western government.

- Gaps in these studies include political partisanship, the global system of states, and liberal authoritarianism.

- These areas are crucial for analyzing liberalism and modern government globally.

- Emphasizing their importance does not negate the value of the governmentality perspective.

- The aim is to highlight the untapped potential of the governmentality perspective in understanding contemporary politics.

Chapter 5. Historical Institutionalism

- Historical institutionalism focuses on big outcome-oriented questions in political analysis.

- It centers on historical and conjunctural explanations, particularly emphasizing institutions.

- Scholars intervene in theoretical debates, often making mid-range political institutional arguments.

- Meta-theoretical debates, especially on path dependence, are central to historical institutionalist scholarship.

- Methodologically diverse, historical methods are considered particularly important.

- Originating in comparative politics, it emerged to bring the ‘state back in’ and analyze political outcomes with historical sophistication.

- Reacting against pluralism, Marxism, behaviorism, and rational choice modeling.

- Institutions are seen as results of large-scale, long-term processes, not created for functional reasons.

- Historical institutionalists engage in deep historical research to trace the persistence of institutions and their unintended consequences.

- Research often results in books or long journal articles with a deep knowledge of specific countries and time periods.

- Disagreements exist within historical institutionalism on theoretical, meta-theoretical, and methodological tenets and practices.

- Not all historical institutionalists rely on political institutionalist explanations or follow a path-dependent approach.

- Focus on comparative public social policy is common within historical institutionalist research.

- Promises include insights into political phenomena and explanations grounded in historical context.

Institutional Arguments and Historical Institutionalism

- Historical institutionalism defines institutions as emergent, higher-order factors influencing political processes.

- Institutions can be constraining or constitutive, shaping political actors’ interests and participation.

- Political institutionalists focus on formal or informal procedures, routines, norms, and conventions in the polity.

- Sociological institutionalists have a broader view, including cognitive scripts, moral templates, and symbol systems.

- Influence and durability of institutions depend on inculcation in political actors and involve material resources.

- Two forms of institutional influence: constraining (limiting conditions for mobilization) and constitutive (establishing available models for action).

- Political institutionalists view actors with a logic of self-interest, while sociological institutionalists see a logic of appropriateness.

- Historical institutionalists provide multi-causal explanations, often involving meso-level political organization.

- Complete explanations are configurational, implicating a conjunction of institutions, processes, and events.

- Explaining institutional change requires causal claims beyond institutions, often involving crises, social movements, or new governments.

- Historical institutionalists may not always identify as such, more prevalent in political science than sociology.

- Comparison in historical institutionalism often means contrast, emphasizing differences in political processes and outcomes.

- Path-dependent arguments highlight how initial decisions about institutions shape future political possibilities.

Path Dependency and Historicism

- Historical institutionalists focus on time order and path dependence for explanation.

- Narrative causal accounts emphasize when events happen as key to their influence.

- Time matters through path dependence, where critical junctures or choice points shape institutions.

- Path dependence creates increasing returns and self-reinforcing processes.

- Lock-in occurs when specific events lead to the removal of political alternatives.

- Political actors reorient their lives around policies, making reversal difficult.

- Disagreement on the centrality of path dependency exists among historical institutionalists.

- Strong version suggests rare but crucial path-dependent processes; weak version sees ubiquity.

- ‘Layering’ theory suggests incremental changes lead to reinforcing patterns.

- Policy feedback mechanisms include state-building, interest group creation, influence of private institutions, promotion of political participation, and ideational legacies.

- Path-dependent theorizing faces difficulties, especially in counterfactual claims and constant challenges.

- Assessing true strength of institutions or policies requires varied challenges, which rarely occur.

- Path dependence may overlook how institutions shape possibilities for later political contestation.

History as a Methodological Approach

- Historical institutionalists use historical methods with variations in interpretation.

- Extensive knowledge of cases through mastery of historiography and tracing processes over time.

- Some focus on one or a few country-level cases, while others act more like historians relying on primary sources.

- Criticized for having too few cases for numerous explanations.

- Works strategically deploy comparisons or trace historical processes to cast empirical doubt on alternative explanations.

- Analyze large-scale contexts and processes often unnoticed in event-focused data analysis.

- Questions are motivated by comparative and theoretical aspects, even if not all engage in cross-national comparisons.

- Theoretical argumentation is configurational and multi-causal, similar to Boolean analytical techniques and fuzzy set analyses.

- Historical institutionalists address puzzles with comparative motivations and implications.

- Limited use of data sets for statistical manipulation; focus on explaining specific outcomes.

- Some consider it insufficient to rely on secondary sources, emphasizing the importance of primary sources.

- Warning against biases and gaps in historiography, archival research is seen as essential for understanding key actors’ perspectives.

- Methodological challenges include the time-consuming nature of historical research and the need for skills in document interpretation.

- Criticisms include deploying too few cases, selecting on the dependent variable, and limitations in making causal claims stick.

- Strategies to address limitations include research design, most similar systems design, and breaking down large country cases.

- Examining positive cases is seen as a valid research strategy, especially in explaining unusual occurrences.

The Future of Historical Institutionalism

- Historical institutionalism addresses questions often ignored, relying on historical methods.

- Big picture analyses remain relevant, but historical institutionalists can increase influence.

- Emphasis on theory needed; current theorizing often lacks generality and analytical clarity.

- Scope conditions should be understood analytically; theorizing beyond specific cases is crucial.

- Intervention in debates between political and sociological institutionalists could enhance theoretical development.

- Roles of ideas in historical institutionalism need greater attention, particularly from a political institutionalist perspective.

- Attention to the influence of ideas can address fine-grained, change-oriented questions.

- Theoretical cases discovered or created in research process can contribute to conceptual development.

- Scholars should ask, “What is the case a case of?” to refine understandings of more general populations.

- Deep knowledge of political developments in historical work can revitalize standard quantitative scholarship.

- Historical institutionalists can identify meaningful quantitative indicators and contribute to advancing knowledge.

- Dialogue between small-N historical studies and large-N quantitative studies can lead to intellectual progress.

- Historical analyses can adjudicate among theories and address variance in larger statistical patterns.

- Institutionalist approaches benefit from cross-fertilization of research methods, combining rigorous statistical tests with more ambitious data analysis.

Chapter 6. Sociological Institutionalism and World Society

Introduction

- Sociological institutionalism, applied to international issues, has led to a literature on ‘world society.’

- Scholars in this tradition focus on understanding how global institutions, world culture, and transnational associations shape states, organizations, and individuals globally.

- World society perspective emphasizes culture, knowledge, and authority from global structures rather than actors’ resources and military capabilities.

- Predicts surprising global conformity and distinctive patterns of disorganization or ‘loose coupling’ among social actors.

- Historical roots trace back to John W. Meyer and collaborators at Stanford University in the 1970s and 1980s.

- Reacts against functionalism and perspectives emphasizing economic and military power.

- Seeks to explain global change, especially the diffusion of Western-style state policies, through emerging global institutions and a common world culture post-World War II.

Institutionalisms

- Institutional perspectives shift focus from individual actors to the social context.

- There’s a continuum in institutionalisms, ranging from interest-seeking rational actors to ‘stage actors.’

- World society theory places actors as enactors of social or cultural rules from their wider environment.

- Economic institutionalism assumes strong interested actors making strategic choices in institutional arrangements.

- Historical institutionalism emphasizes path-dependent ways in which historically emergent features shape behavior.

- Sociological neo-institutionalism asserts that social context shapes or even ‘constitutes’ social actors, defining their identities and goals.

- Neo-institutional scholars draw inspiration from cultural and phenomenological traditions.

- Emphasis on macro-social dynamics contrasts with methodological individualism in contemporary sociological research.

World society and world culture

- World society tradition originated from comparative research on education and governance in the 1970s.

- Education systems in sub-Saharan Africa appeared similar to Western societies despite different labor markets.

- Isomorphism, or similarity across societies, was explained by conformity to dominant cultural models.

- Cultural models act as blueprints defining a ‘normal’ nation-state, diffusing globally through international organizations.

- The tradition emphasizes commonalities in international discourses, focusing on strong patterns and trends.

- Empirical research studies the top-down process of global model diffusion to nation-states with strong organizational links.

- Seemingly disparate nation-states exhibit structural similarity in constitutions, ministerial structures, and policies.

- Common goals of modern nation-states reflected in areas like expanded educational systems, environmental protection, and science promotion.

The content of world culture

- World society theory focuses on modernity and unpacks the institutionalized culture of modern society.

- Social actors are characterized as products of this culture, emphasizing rationalization, universalism, belief in progress, and individualism.

- Foundational cultural assumptions undergird global discourse and organization, influencing various movements and initiatives.

- Global culture is seen as a historical product, shaped by events like Christendom, the Enlightenment, and shifts in global power dynamics.

- European dominance and colonial expansion spread Western ideas globally, but world society scholars resist the notion of cultural hegemony enforced by arms.

- The cultural system evolves autonomously; for example, liberal ‘American’ ideals expressed in the UN Declaration of Human Rights have spurred an international human rights movement beyond U.S. intentions.

- Recent research delves into the origins and content of world society, exploring how world culture saturates various aspects of social life, including law, organizations, religion, national identity, and even anti-globalization movements.

- Scholars like Lechner and Boli (2005) and Frank and Gabler (2006) examine world culture’s influence on diverse areas such as university curricula worldwide.

Disorganization and loose coupling

- Cultural/phenomenological institutionalisms reject actor-centrism and functionalism.

- World society theory views states, organizations, and individuals as loose structures with internal inconsistencies.

- States lack coherent interests or identities, drawing haphazardly upon cultural models from the institutional environment.

- Ritualized enactment of global models may be loosely related to policy implementation, especially in impoverished countries.

- Disjunctures are the norm in the world society perspective.

- The perspective recognizes and makes sense of the complex forms of loose coupling observed in modern organizations.

- Research supports the idea of loose coupling in both case studies and quantitative studies.

- Examples include anti-female genital cutting reforms not necessarily diminishing the practice and human rights accords not improving records in abusive countries.

- Decoupling is pervasive in developing countries, where economic globalization pressures lead to varied science policies without a boost in the scientific labor force.

- Loose coupling doesn’t imply the absence of real change; institutional forces can generate systematic change across organizational levels.

Related traditions

- Complementary perspectives to world society theory include constructivism in political science and sociological work on transnational civil society and social movements.

- Constructivism in International Relations emphasizes the influence of norms on state behavior, propagated by non-state actors or “norm entrepreneurs.”

- Recent work on transnational social movements shares commonalities with world society theory, including an emphasis on international association and cultural frames as sources of mobilization.

- These perspectives often retain actor-centrism and emphasize power, contrasting with the rejection of such elements in cultural/phenomenological institutionalisms.

- Science studies on performativity align with world society theory, focusing on authoritative knowledge, epistemic communities, and policy professionals as sources of global cultural myths.

- World society scholarship also intersects with Foucaultian-inspired studies of the state, global institutions, and ‘governmentality,’ despite de-emphasizing power and emphasizing ‘taken-for-grantedness’ and authority.

- The dominant culture of ‘high modernity’ and trends toward rationalization described in world society research resemble the disciplinary regimes and systems of governmentality in the Foucaultian tradition.

Myths and Misperceptions

Criticism 1: World society theory ignores actors, interests, and power

- De-emphasizes actors and interests, viewing them as derivative features of the institutional environment.

- Challenges the conventional emphasis on coercive power, highlighting the pervasive role of authority in social life.

Criticism 2: World society theory cannot explain the origins of cultural forms or cultural change

- Addresses the misconception that world society theorists overlook the origins question.

- Growing studies explore how evolving global institutions contribute to the emergence and transformation of cultural forms.

Criticism 3: World society theory is equivalent to the INGO effect

- Acknowledges the central role of INGOs in policy diffusion.

- Emphasizes that the cultural dimensions of world society theory go beyond organizational aspects and predict diffusion along specific cultural lines.

Criticism 4: World society theory is equivalent to ceremony without substance

- Highlights the ceremonial or ritualized character of social life according to world society theory.

- Counters the misconception that world society theorists envision a state of enduring hypocrisy, emphasizing the convergence of substance and ceremony over time.

Criticism 5: World society theory predicts that everything will diffuse

- Clarifies that world society theory is as much a theory of non-diffusion as diffusion.

- Predicts factors like the assertion of collective goods, articulation with global institutions, and international organizational carriers influencing diffusion.

Criticism 6: World society theory is a normative and/or teleological perspective similar to modernization theory

- Differentiates world society scholarship, focusing on understanding the consequences of institutionalized cultural views, from normative endorsement or teleological perspectives.

Criticism 7: World society theory fails to attend to mechanisms

- Recent empirical work addresses the criticism by documenting various carriers of institutionalized cultural models.

- Acknowledges the complexity of cultural processes and the challenge of identifying specific mechanisms responsible for diffusion or change.

New Directions in World Society Theory

Role of Individual Actors:

- World society theory traditionally overlooked the role of individuals in institution-building.

- Recent arguments emphasize the essential role of individuals in the diffusion of global norms, especially in contexts emphasizing human rights and actorhood.

- Individuals both influenced by and influence global institutions, acting as agents or resistors.

- The concept of ‘inhabited institution’ suggests that bureaucratization depends on personalities, interpretations, and policies.

- Research links world polity theory with transnational movements, showing how global processes impact social mobilization.

Theories of Change:

- Institutional change is explained as a ‘learning’ process, where organizations or states adopt successful practices from others.

- Learning involves copying socially constructed ‘lessons’ from successful actors and translating them through professionals and experts.

- Changes may occur with the rise of successful new actors or during crises, creating openings for policy shifts.

- World polity theorists are skeptical about the effectiveness of these processes, as indicators of success may be constructed and misleading.

Explaining Consequences and Outcomes:

- Scholars in the world polity tradition focus on substantive outcomes resulting from global institutional processes.

- Early research questioned the link between institutional processes and specified outcomes.

- World polity pressures have led to significant changes, such as the expansion of education, bureaucratization, rationalization, and individual empowerment.

- In areas like human rights, discourse alone may not lead to comprehensive changes, and improvements might be confounded by global factors like the legitimacy of authoritarian regimes.

- World polity processes have indirect effects, such as ‘naming and shaming,’ rather than direct sanctions, and may lead to the development of a ‘virtuous regime’ over time.

Concluding Thoughts

- World society literature is evolving, moving beyond early conflicts with functionalism and Marxism.

- Contemporary debates are more nuanced, focusing on various institutionalisms.

- A key future fault line may emerge between cultural/phenomenological institutionalisms and actor-centric approaches, like those in International Relations.

- The world society tradition challenges actor-centrism in social science, particularly in American scholarship.

- Ongoing efforts to counter actor-centrism differentiate the world society tradition from conventional institutional analysis.

- The tradition’s vibrancy hinges on its ability to offer novel predictions and perspectives in global social science.

Chapter 7. Studying Power

- Three dominant methodological traditions in studying power: reputational, structural, and decision-making approaches.

- Reputational approach focuses on those believed to have power, reflecting images of power.

- Structural approach examines strategic positions in central organizations and institutions as central to power.

- Decision-making approach critiques formalistic views and studies actual decision-making processes.

- Scott favors the structural approach, arguing it can incorporate insights from reputational and decision-making approaches.

- Traditionally, these approaches were considered rivals with exclusive paradigms.

- Affinities between theoretical approaches and research methods exist but are not rigid connections.

- Three research traditions associated with power: reputational, structural, and decision-making.

- Reputational approach centers on agents reputed to be powerful, revealing images of power.

- Structural approach focuses on strategic positions and attributes in central organizations and institutions.

- Decision-making approach critiques formal definitions and explores the actual process of decision-making.

- Scott argues for the structural approach, considering it the most beneficial for power research.

- Each tradition employs specific data collection and analysis techniques, common in social sciences.

- Concentration on features of research methods specific to power studies, not a comprehensive coverage.

- Power studies can occur at various levels: national, community, global.

- The choice of the level of analysis raises theoretical and substantive issues.

- Research issues across levels of analysis are generally similar.

Images and Decisions

- Paradigmatic study for reputational approach: Floyd Hunter (1953), focusing on identifying powerful individuals based on community perceptions.

- Hunter’s “positional” approach sees power as acts of individuals in strategic positions, emphasizing the resources tied to social positions.

- Hunter’s study in Atlanta aimed to identify powerful individuals in business, government, civic affairs, and society leaders.

- Key informants named leaders in each arena, and judges selected a “top ten of influence” in each category.

- Limitation: Lack of African Americans on the list led to an ad hoc extension to study black community power, revealing a divided structure.

- Sampling problem: Hunter’s claim of representativeness raises issues about the nature of the sample.

- Reputational approach provides evidence on images of power rather than actual power holders.

- Paradigmatic study for decision-making approach: Robert Dahl (1961), critiquing Hunter and structural approaches.

- Dahl defines power as influencing others to do something they wouldn’t otherwise do, emphasizing direct investigation of decision-making.

- Dahl’s study in New Haven identified positions with potential power, investigating participants in key decisions.

- Dahl’s methodology measured the actual participation of position holders in specific key decisions.

- Issues with decision-making approach: Uncertainty in accessing decision-makers, potential non-decision-making processes, and the need for a structural framework.

- Dahl argued for pluralistic power in New Haven, challenging elitist views.

- Critique of decision-making approach: Need to investigate non-decision-making processes and consider the significance of potential power inherent in structural positions.

- Structural concerns, eliminated by Dahl, must find a place in a comprehensive investigation of power.

Structures of Power

- Mills’ (1956) paradigmatic study focuses on structural positions in the U.S., emphasizing power residing in top positions of institutional hierarchies.

- Power is seen as the ability to realize one’s will, tied to the attributes of positions rather than individual identity.

- Mills identifies a power elite through overlapping groups: the corporate rich, the political directorate, and the warlords (military).

- Comprehensive data collection using documentary sources to identify positions in economic, political, and military hierarchies.

- Boundary issues in defining positions: arbitrary decisions needed for system boundaries, e.g., defining “top” corporations or important political/military positions.

- Mills’ structural analysis emphasizes overlapping memberships in the power elite.

- Social network analysis becomes central in structural research, examining cliques and sub-groupings.

- Domhoff (1967, 1971, 1979, 1998, 2009) and others influenced by him use the structural approach to investigate social background and policy preferences of powerful positions.

- Studies explore networks in the special-interest process, policy formation, candidate selection, and ideology process.

- Similar approach in Britain by Guttsman (1963), Miliband (1969), and Scott (1991c), exploring old boy networks and policy networks.

- Structural analysis crucial in economic power studies, examining interlocking directorships and intercorporate shareholdings.

- Critical examination of managerialist ideas, revealing structures of bank centrality in coordinating corporate power.

- Works by Mintz and Schwartz in the U.S. and Scott in Britain document how finance capitalists influence corporate power structures through interlocking directorships.

Conclusion

- Each tradition (reputational, structural, decision-making) has produced valuable work in studying power.

- Each tradition also has limitations that need consideration.

- No single tradition has a monopoly on truth; combining them in a research design is ideal (Dowding 1996).

- Structural approach is argued to be the best for integrating research on decision-making participation and images of power.

- Structural approach provides powerful techniques for mapping and measuring power relations.

- It offers an essential framework for understanding decision-making power processes.

- Dowding (1995) downplays structural concerns in policy network research, but structural analysis is deemed crucial in this context.

Chapter 8. Comparative Political Analysis

Six Case-Oriented Strategies

Context

- Case-oriented comparative political analysis is not seen as a primitive form of quantitative research; it has its distinctive analytic logic.

- Its focus on small Ns is not what makes it distinctive; rather, it is well suited for theory building.

- The key difference is that case-oriented work analyzes asymmetric set relations, while conventional quantitative analysis focuses on symmetric relationships among variables.

- Six case-oriented comparative strategies illustrate its distinctiveness and provide guidance to researchers.

- Recent discussions often refer to the impact of “Designing Social Inquiry: Scientific Inference in Qualitative Research” (King, Keohane, Verba, 1994).

- The view that qualitative, case-oriented research is less refined than quantitative research has persisted for decades in various forms.

- Neil Smelser (1976) and Przeworski and Teune (1970) share the argument that proper names should be removed from macro-comparative inquiry, but this is questioned.

- Case knowledge is valuable, and in-depth knowledge of cases is crucial for empirical generalization.

- The chapter aims to provide evidence that case-oriented inquiry is not inferior to quantitative research and describes six strategies to illustrate its distinctiveness.

- Qualitative and quantitative research should be recognized and celebrated for their respective strengths rather than compared using inappropriate standards.

Connecting Conditions and Outcomes: The Limitations of Correlation

- Many quantitative techniques for assessing causal relations use symmetric measures of association, such as the correlation coefficient.

- Symmetric measures give equal weight to an argument and its mirror, creating potential issues in interpreting results.

- For instance, a correlation between stability and elite fractionalization tests both the argument and its mirror, making it less precise.

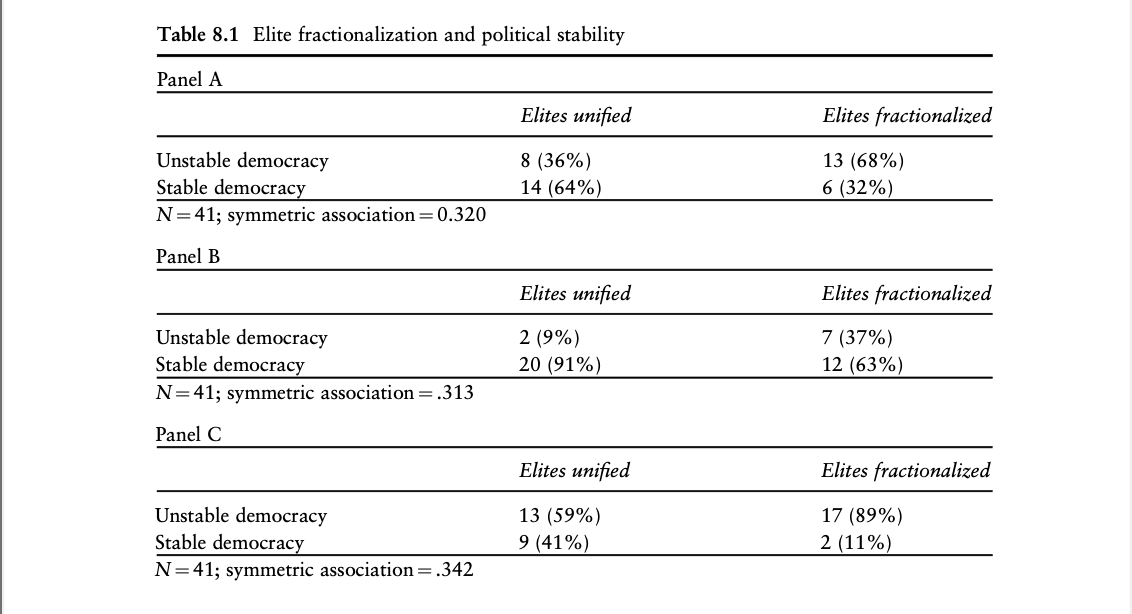

- Table 8.1: panel A illustrates a symmetric association, showing support for both the argument and its mirror.

- Table 8.1: panel B has a statistically significant positive relationship, but it supports the mirror argument more strongly.

- Table 8.1: panel C shows strong support for the initial argument, but the mirror argument is not supported.

- Symmetric measures are insensitive to subtle differences in argumentation and evidence, making them less precise for many asymmetric arguments.

- Arguments formulated symmetrically are less empirically precise and harder to connect to empirical cases and questions.

- Symmetric arguments may be true even if the majority of cases do not align with the expected outcomes, as shown in Table 8.1: panel B.

Connecting Conditions and Outcomes: The Case-oriented Template

- Researchers studying cases often focus on qualitative changes, analyzing shifts or transformations over a specific time period.

- Qualitative changes involve specific combinations of causally relevant conditions, forming causal recipes.

- Causal recipes require all relevant ingredients to be in place for a change to occur and involve processes and mechanisms.

- The specification of a causal recipe in a case study can be considered a testable hypothesis for other cases.

- The example of ‘Three Strikes and You’re Out’ in California illustrates a causal recipe involving four conditions.

- A researcher can move in two directions: selecting other instances of punitive policy change or finding other instances of the same recipe.

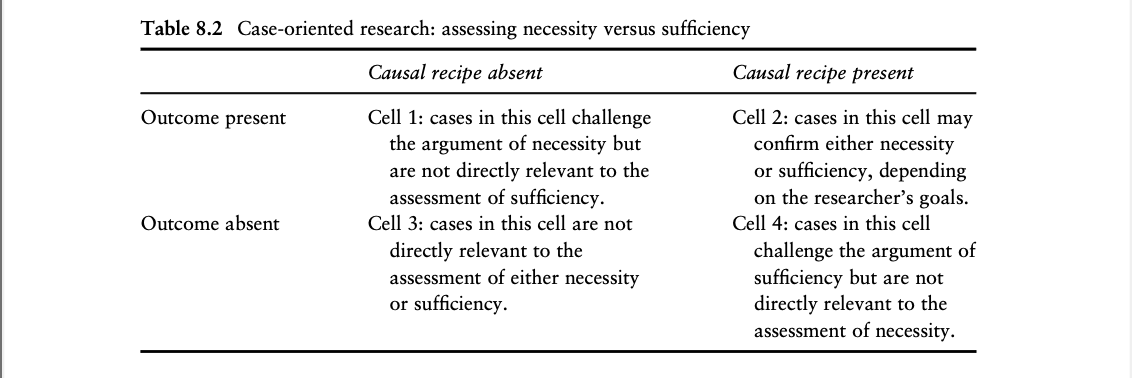

- Two set-theoretic approaches are discussed: assessing if instances of the outcome constitute a subset of instances of causal conditions (necessity) and vice versa (sufficiency).

- Strategies involve examining other states with major changes to their penal codes to establish consistency with necessity or sufficiency.

- Table 8.2 summarizes the case-oriented approach, emphasizing the disaggregation and partitioning of the standard 2×2 table.

- Different research strategies are motivated by different ideas about whether conditions in the recipe are necessary-but-not-sufficient or sufficient-but-not-necessary.

- In case-oriented research, the focus is on the interpretation and analytic use of different cells in the 2×2 table, contrasting with variable-oriented research.

- Symmetric statistics in variable-oriented research reward having as many cases as possible in cell 3 (null-null), which plays no direct role in case-oriented assessments of sufficiency or necessity.

Six Strategies of Case-oriented Comparative Analysis

Sufficiency-Centred Strategy #1: Adding to the Recipe

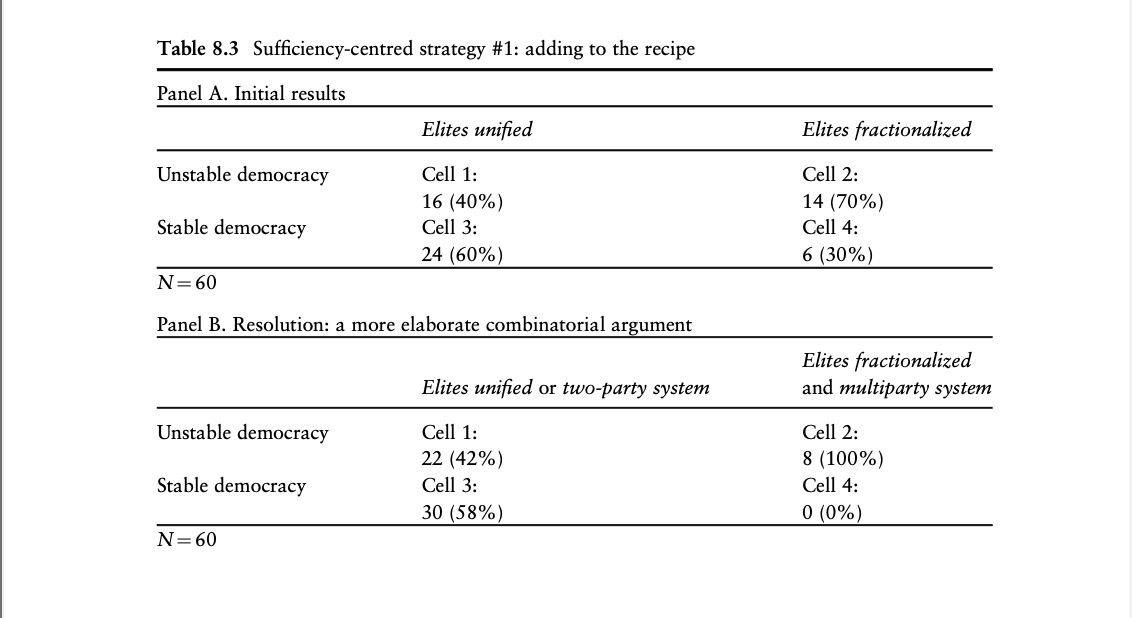

- Elite fractionalization initially considered sufficient for democratic instability.

- Mixed evidence prompts comparison of cases with and without instability.

- Researcher refines the argument, combining elite fractionalization with a multi-party system.

- Elaborates the causal argument, making it more restrictive and less inclusive.

- Shift from panel A to panel B in Table 8.3 establishes set-theoretic connection between cause and effect.

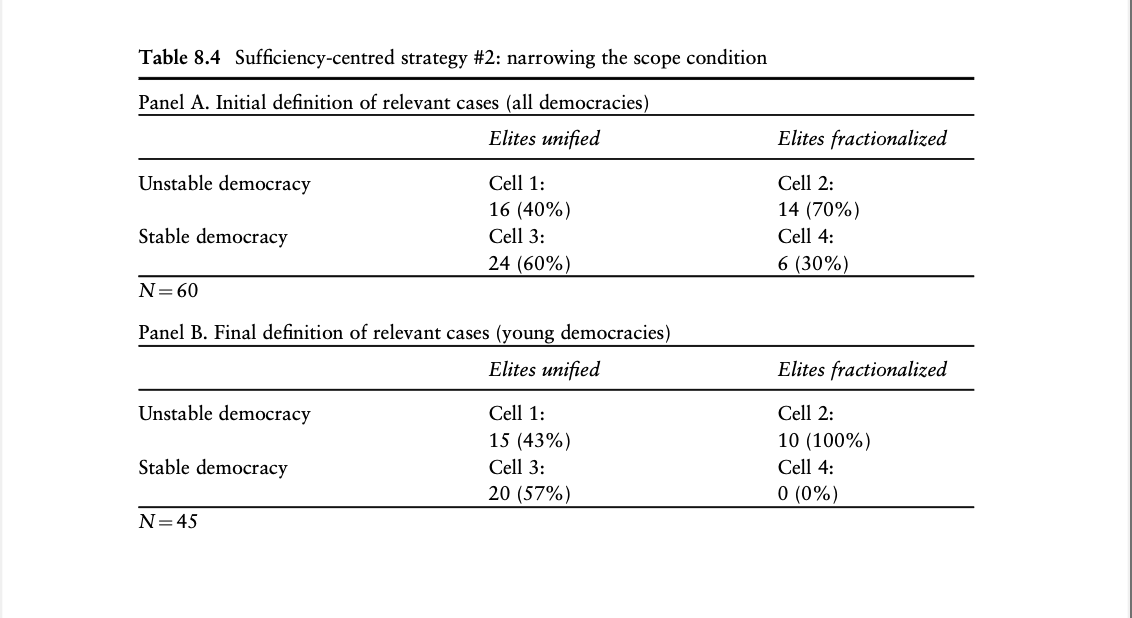

Sufficiency-Centred Strategy #2: Narrowing the Scope Condition

- Initial cross-tabulation shows cases with elite fractionalization and democratic stability.

- Focus on scope conditions and relevance of cases, especially in cell 4.

- Researcher revises scope condition, excluding ‘established’ democracies.

- Analysis recomputed in Table 8.4: panel B, narrowing the scope condition but sacrificing statistical power.

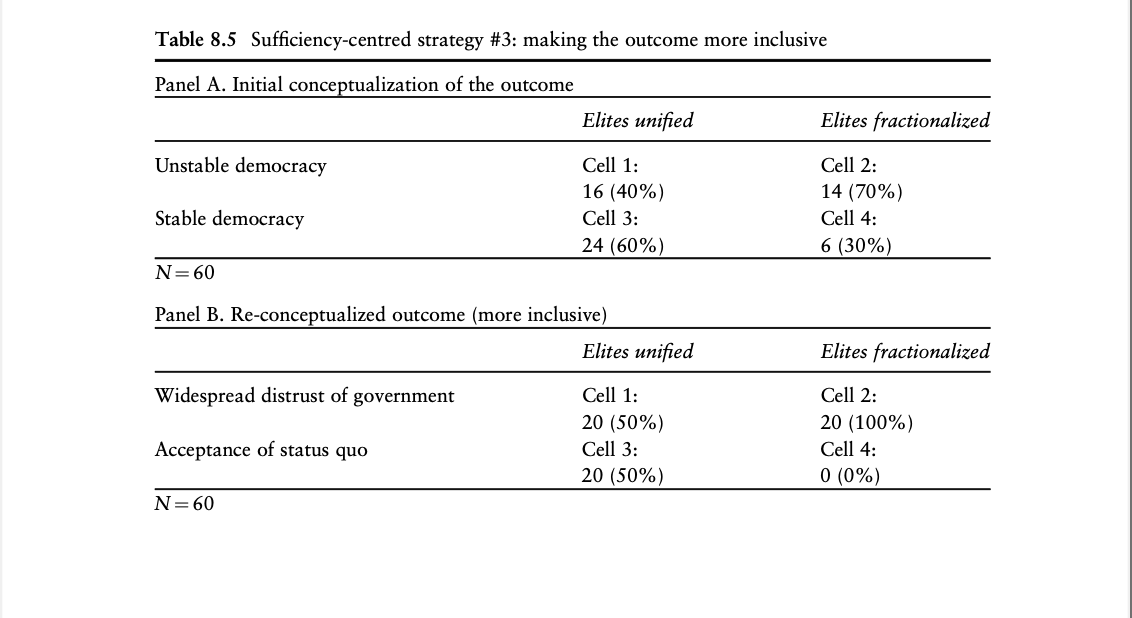

Sufficiency-Centred Strategy #3: Making the Outcome More Inclusive

- Examines the conceptualization of the outcome.

- Broadens the definition of ‘instability’ to ‘widespread distrust of government’ in Table 8.5.

- Shifts cases from cell 4 to cell 2, establishing set-theoretic patterns consistent with sufficiency.

- Reconceptualization aligns with ‘retroductive’ logic of qualitative research.

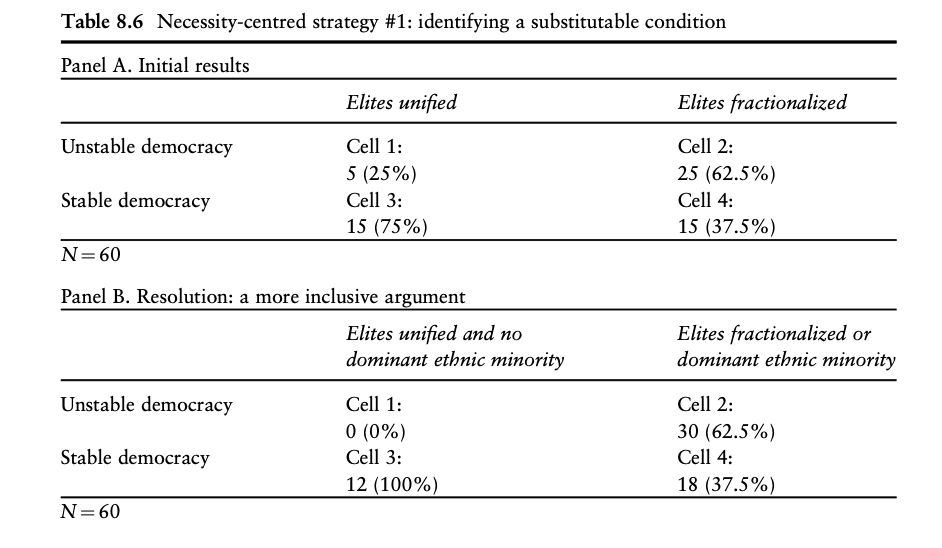

Necessity-Centred Strategy #1: Identifying a Substitutable Condition

- Investigates elite fractionalization as a necessary condition for democratic instability.

- Mixed evidence prompts examination of cases lacking fractionalization (cell 1).

- Identifies ‘economically dominant ethnic minority’ as a substitutable necessary condition.

- Reformulates the argument, making it more inclusive through logical OR in Table 8.6.

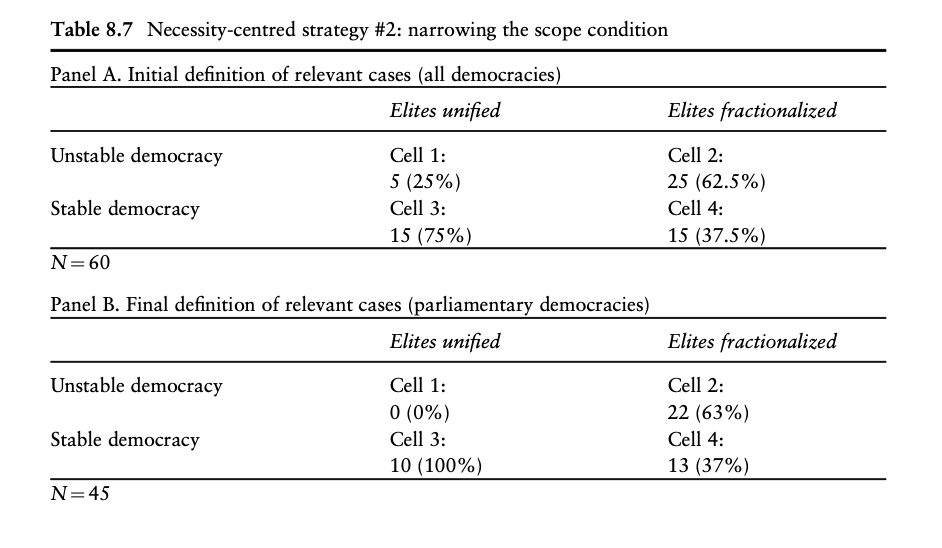

Necessity-Centred Strategy #2: Narrowing the Scope Condition

- Similar to sufficiency strategy, focuses on cell 1 cases.

- Studies relevance and scope conditions, drops cases not meeting criteria.

- Respecifies set of relevant cases, narrowing it to parliamentary systems in Table 8.7.

- Empty cell 1 signals explicit connection between cause and outcome.

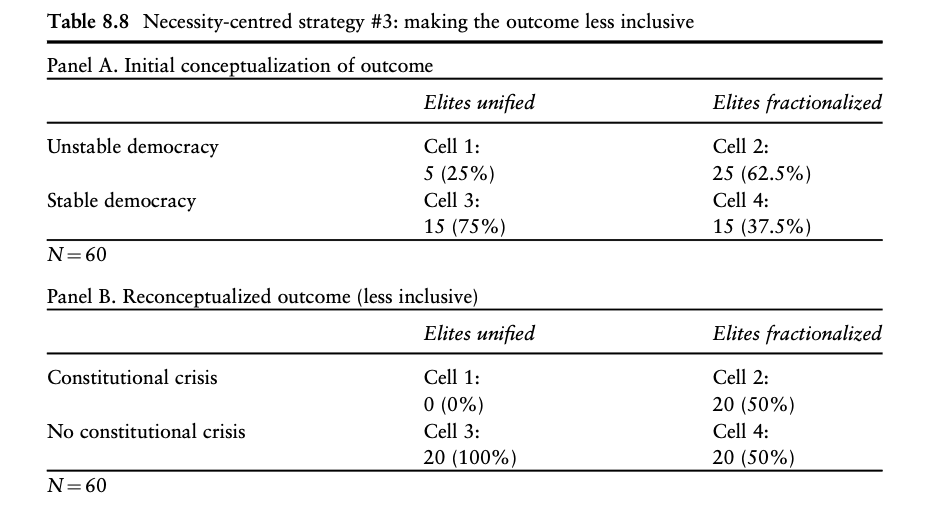

Necessity-Centred Strategy #3: Making the Outcome Less Inclusive

- Examines cell 1 cases for outcomes different from cell 2.

- Narrows the definition of the outcome, shifting from democratic instability to constitutional crisis in Table 8.8.

- Excludes cell 1 cases from the outcome, transferring them to cell 3.

- Gain is decisive from a set-theoretic viewpoint, establishing a pattern consistent with causal necessity.

- Conventional variable-oriented strategies use symmetric measures of association.

- Symmetric measures fail to distinguish between a causal argument and its mirror.

- These measures focus on the distribution of cases across all four cells in a 2×2 table.

- They are incapable of directly assessing either necessity or sufficiency.

- Case-oriented research focuses on strategies that empty either cell 4 (establishing sufficiency) or cell 1 (establishing necessity).

- These tasks are treated as analytically distinct, emphasizing sufficiency or necessity.

- Case-oriented research may culminate in tabular patterns with little explanatory gain in variable-oriented research.

- From a set-theoretic viewpoint, these differences can be decisive.

Conclusion

- The case-oriented approach deconstructs the cross-case correlation into two main components.

- Using the 2×2 table, conventional variable-oriented analysis conflates two different research strategies.

- Sufficiency-centered strategies focus on causal conditions that are subsets of the outcome (second column of Table 8.2).

- Necessity-centered strategies focus on causal conditions that are supersets of the outcome (first row of Table 8.2).

- Different ideas about the connection between cause and outcome motivate distinct analytic strategies.

- The demonstrations in this chapter use the basic 2×2 table for clarity.

- Similar issues arise in more sophisticated forms of analysis beyond the elementary 2×2 table.

- For example, Pearson’s correlation coefficient also conflates the two case-oriented analytic strategies.

- Fuzzy set-theoretic procedures with fuzzy sets can disentangle these assessments in more complex analyses.

- These fuzzy set-theoretic procedures parallel those demonstrated with crisp sets and 2×2 tables.