Constitutional Framework

Part I

CH1. Historical Development of Constitution of India

During 200 years of British rule in India, various acts were passed to better control this diversified large land under both Company and the Crown rules. These acts greatly influence the country’s present political structure and various constitutional provisions.

Timeline of British Rule in India

1. The Company Rule(1773-1857)

2. The Crown Rule (1858-1947)

2. The Crown Rule (1858-1947)

Important Acts passed during British India and their Provisions

Rule in India (1773-1858)

1. Regulating Act, 1773

Features of the Act

- The act was the first attempt to regularize company affairs in India.

- It laid the foundation of Central Administration in India.

- Governor of Bengal became Governor-General of Bengal (Lord Warren Hastings was the first Governor-General of Bengal).

- Created Executive Council of 4 members to assist Governor-General of Bengal.

- Made Governors of Madras and Bombay presidencies subordinate to Governor-General of Bengal.

- Provisioned for setting up the Supreme Court of Calcutta with 1 Chief justice and 3 other judges.

- Prohibited the company’s servants from indulging in any private trade and accepting bribes from locals.

- “Provisioned for the Court of Directors of the Company to report to the British Government regarding its revenue, civil, and military affairs in India.”

2. Act of Settlement or Amending Act, 1781

Features of the Act

- This act was passed to amend the Regulation Act, 1773.

- Safeguarded the Governor-General and its council from the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court. Also provided immunity to the servants for their official actions.

- Exempted matters related to the Company’s revenue from the Supreme Court’s jurisdiction.

- Required the Supreme Court to administer the personal law of the defendant.

- Empowered the Governor-General and its Council to frame regulations regarding Provincial Courts and Councils.

3. Pitt’s India Act, 1784

Features of the Act

- Established a system of Dual Government. Provided for the Court of Directors to manage its commercial affairs while a new body called the Board of Control managed its political affairs.

- Empowered the Board of Control to supervise and direct civil and military operations and revenues of India’s British possessions.

Significance of the Act

- First time acknowledged Indian Territory under control of the company as India’s British possessions.

- The British government became the Supreme Controller of the Company’s affairs and administration in India.

4. Charter Act of 1793

- The Act extended the company’s rule over the British territories in India.

- It prolonged the company’s trade monopoly in India for an additional 20 years.

- The Act established that the “acquisition of sovereignty by the Crown subjects is on behalf of the Crown and not in its own right,” clearly stating that its political functions were on behalf of the British government.

- The company’s dividends were allowed to be raised to 10%.

- The Governor-General was granted enhanced powers, enabling him to override his council’s decisions under certain circumstances.

- He was also given authority over the governors of Madras and Bombay.

- When the Governor-General was present in Madras or Bombay, he would supersede the governors of Madras and Bombay.

- In the Governor-General’s absence from Bengal, he could appoint a Vice President from among the civilian members of his Council.

- The composition of the Board of Control changed, requiring a President and two junior members, who were not necessarily members of the Privy Council.

- The staff’s salaries and the expenses of the Board of Control were now charged to the company.

- After all expenses, the company had to pay the British government Rs.5 Lakhs from the Indian revenue annually.

- Senior company officials were prohibited from leaving India without permission, and doing so would be considered as a resignation.

- The company was granted the authority to issue licenses to individuals and company employees for trading in India, known as ‘privilege’ or ‘country trade,’ which eventually led to shipments of opium to China.

5. Charter Act, 1813

Features of the Act:

- Abolished India’s trade monopoly except for trade in tea and trade with China.

- Allowed Christian missionaries to come to India and start their religious awakening in India.

- Authorized Local Governments in India to levy taxes on the people of India.

6. Charter Act, 1833

Features of the Act

- Made Governor-General of Bengal as the Governor-General of India and vested all civil and military powers (Lord William Bentinck became the first Governor-General of India).

- Empowered Governor-General of India with the exclusive legislative powers of entire British India.

- The Company became a purely administrative body.

7. Charter Act, 1853

Features of the Act

- Separated legislative and executive functions of the Governor-General’s Council.

Governor-General’s Council

Governor-General’s Council - Provided for a separate 6 members Indian Legislative Council to function as mini parliament.

- Provisioned for open competition system for Indian Civil Services for Indians also.

- Introduced local representation in the Indian (Central) Legislative Council. (out of 6 members, 4 to be appointed by the local governments of Madras, Bombay, Bengal, and Agra)

Rule in India (1858 to 1947)

1. Government of India Act, 1858

- Post-1857 revolt British Government took control over India’s entire territory under Company rule. The act is also known as the Act of Good Government of India.

Features of the Act

- Changed the post of Governor-General of India to Viceroy of India and made him the representative of India’s British Crown (Lord Canning was the first Viceroy of India).

- Abolished the Board of Control and Court of Directors.

- Created office of Secretary of State for India, vested with complete authority and control over Indian administration.

- Created a 15 member Council of India to assist the Secretary of State for India.

2. Indian Councils Act, 1861

Features of the Act

- Empowered the Viceroy to nominate some Indians as the non-official members under his expanded council (Lord Canning nominated 3 Indians: the Raja of Benaras, the Maharaja of Patiala, and Sir Dinkar Rao).

- Decentralized legislative powers by empowering the Bombay and Madras Presidencies.

- Provided for establishing new legislative councils for Bengal, North-Western Provinces, and Punjab. The act established the Portfolio system in Indian administration. It empowered the Viceroy to make rules and orders for the Council’s better functioning and made members of the council in-charge and authorized to issue orders regarding one or more government departments allocated to them.

- Empowered the Viceroy of India to issue ordinances in an emergency without the legislative council’s concurrence and with a validity of 6 months.

3. Indian Councils Act, 1892

Features of the Act

- Increased number of non-official members in the Central and Provincial legislative councils.

- Empowered the legislative councils by discussing budget and addressing questions to the executive.

- Provided for the nomination of some non-official members of the:

(i) Central Legislative Council by the viceroy on the Provincial Legislative Councils’ recommendation and the Bengal Chamber of Commerce, and that of the Provincial Legislative Councils by the Governors on the district board’s recommendation, municipalities, universities, trade associations, zamindars, and chambers.

4. Indian Councils Act, 1909

- Also known as Morley-Minto Reforms.

Morley-Minto Reforms

Morley-Minto Reforms - The number of members in the Central Legislative Council was increased from 16 to 60, and the number of members in the Provincial Legislative Council was also increased but not uniformly.

- Empowered the members of legislative councils at both levels to ask supplementary questions, move resolutions on the budget, etc.

- Provided for the association of Indians with the executive councils of the Viceroy and Governors (Satyendra Prasanna Sinha was the first Indian to join the Viceroy’s executive council as the Law member).

- Introduced system of communal representation for Muslims and separate electorate for them.

5. Government of India Act, 1919

Features of the Act

- Also known as the Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms.

- Separated Central and Provincial subjects.

Division of Provisional Subjects

Division of Provisional Subjects

- Provincial subjects were further divided into transferred subjects and reserved subjects. Transferred subjects were to be governed by the Governor with ministers of the legislative council, and Governor’s reserved subjects were to be managed by his executive council.

- Introduced bicameralism and direct elections in the country.

- Provided that 3 out of 6 members of the Viceroy’s executive council were to be Indian.

- Provided for separate electorates for Sikhs, Indian Christians, Anglo-Indians, and Europeans.

- Granted the franchise to a limited number of people based on property, tax, or education.

- Created the new office of the High Commissioner for India in London.

- Provided for setting up a Central Service Commission for recruiting civil servants.

- Separated provincial budgets from the Central budget and authorized provincial legislatures to enact their budgets.

Significance of the Act

- This was intended towards a responsible government in British India; the role of elected members in the legislature was advisory, and the Viceroy retained control of the central government.

- Later, with the passage of the Rowlatt Act, the government suppressed the voices of Indians as it empowered the Government to imprison any person without trial and conviction in a court of law.

- The Simon Commission was then appointed in 1927, which was greatly opposed by Indians.

6. Government of India Act, 1935

Events leading to Act

- Incorporating the recommendations of the Simon Commission (1930).

- Civil Disobedience Movement (1930).

- Recommendations of Round Table Conferences (1930, 31, and 32).

- Gandhi-Irwin Pact.

- Poona Pact between Gandhi Ji and B.R. Ambedkar (1932).

Features of the Act

- Provided for establishing an All India Federation consisting of provinces and princely states.

- Divided powers into three lists: Federal list (for Centre, with 59 items), Provincial list (for Provinces, with 54 items), and the Concurrent list (for both, with 36 items). The Viceroy was empowered with all the residuary powers.

- Abolished dyarchy in the provinces and introduced provincial autonomy. It introduced responsible Governments in provinces where the Governor needed to work on ministers’ advice, responsible to the provincial legislature.

- Provided for the adoption of dyarchy at the Centre. Federal subjects were divided into transferred subjects and reserved subjects.

- Introduced bicameralism in 6 out of 11 provinces (Bengal, Bombay, Madras, Bihar, Assam, and the United Provinces).

- Divided Federal Budget: 80 per cent non-votable part could not be discussed or amended in the legislature. The remaining 20 per cent of the whole budget could be discussed or amended in the Federal Assembly.

- Provisioned for separate electorates for depressed classes (Scheduled Castes), women, and labour. It extended franchise, and about 10 per cent of the total population got voting rights.

- Abolished the Council of India.

- Established Reserve Bank of India to control the country’s currency and credit.

- Established Federal Public Service Commission, Provincial Public Service Commission, and Joint Public Service Commission.

- Provided for setting up a Federal Court.

Significance of the Act

- Reflected the ambiguity of British commitment to dominion status for India.

- Discussed nothing about the citizens’ rights.

- There was no major impact on the Governor-General’s powers and that of Governors in the provinces.

- Communal electorate further divided Indian society.

- The Constitution so created was rigid, and the power to amend was reserved with the British parliament.

7. Indian Independence Act, 1947

Based on the Muslim league’s demands for a separate nation for Muslims, the then Viceroy of India, Lord Mountbatten, put forth the partition plan, known as the Mountbatten Plan. Both Congress and the Muslim League accepted the plan. The Indian Independence Act of 1947 gave immediate effect to the plan.

Features of the Act

- Ended British rule in India and declared India to be an independent and sovereign state from August 15, 1947.

- It provisioned for India and Pakistan’s partition as two independent dominions with the right to secede from the British Commonwealth.

- It empowered the Constituent Assemblies of the two nations to frame and adopt any constitution of their respective nations and repeal any British Parliament act, including the Independence Act itself.

- It abolished the office of Secretary of State for India and transferred his powers to the Secretary of State for Commonwealth Affairs.

- It deprived the British Monarch of his right to veto bills or ask for a reservation of certain bills for his approval.

- It designated the Governor-General of India and provincial governors as constitutional (nominal) heads of the states.

- It dropped the Emperor of India’s title from the King of England’s royal titles.

- It discontinued the appointment to Civil Services and the Secretary of State of India’s posts and reservation of posts.

- Crown ceased to be the Source of Authority.

Significance of the Act

- As per the provision under the Act, India became an independent nation on 15th August 1947, and the British rule in India came to an end.

- Lord Mountbatten became the last Governor-General of British India and the first Governor-General of India’s new dominion.

- J.L. Nehru became the first Prime Minister of the Country.

- The Constituent Assembly of India, constituted in 1946, became the Parliament of Independent India.

- As per the act’s provision, the princely states were free to join any of the two dominions or set themselves free, which led to a huge unification of the country and curbed the seceding tendencies.

Key Timelines – Constitution of Independent India

Indian Constitution Drafting:

- Constituent Assembly drafted the Indian Constitution, taking almost three years to complete.

- Assembly convened on December 9, 1946.

Committee Creation Proposal:

- On August 14, 1947, a proposal emerged for forming committees.

Drafting Committee Establishment:

- Drafting Committee formed on August 29, 1947.

- Constituent Assembly initiated the Constitution-writing process.

Presidential Involvement:

- Dr. Rajendra Prasad, as President, prepared the draft in February 1948.

Constitution Adoption:

- Constitution adopted on November 26, 1949.

Republic Day and Transformation:

- Constitution came into effect on January 26, 1950, declaring India a Republic.

- On this day, the Assembly transformed into the Provisional Parliament of India until the formation of a new Parliament in 1952.

Constitution Characteristics:

- Longest written constitution globally.

- Comprises 395 articles and 12 schedules.

CH2. Making of the Constitution

M.N. Roy, the first person to put forward the idea of the Constituent Assembly

M.N. Roy, the first person to put forward the idea of the Constituent Assembly

- M.N. Roy first time kept forward the idea of the Constituent Assembly in 1934.

- In 1935, the Indian National Congress for the first time demanded a Constituent Assembly to frame the Constitution of India.

- In 1938 Jawahar Lal Nehru declared that the Constitution of free India must be framed by a Constituent Assembly whose members are to be elected based on an adult franchise. It should be free from any external interference.

- In the 1940s ‘August Offer’ demand was accepted and in 1942 Sir Stafford Cripps was sent to India with a draft proposal on the framing of an independent Constitution to be adopted after World War II.

- Muslim league rejected the proposal as it demanded two dominion states with two separate constituent assemblies.

- Later in 1946, the Cabinet mission put forward the idea of a Constituent Assembly which satisfied both the INC and the Muslim League.

- In November 1946, the Constituent Assembly was constituted under the scheme formulated by the Cabinet Mission Plan.

Constituent Assembly

Constituent Assembly

Plan provisioned the following scheme for setting up the Constituent Assembly of India:

- The total strength of the Constituent Assembly was 389. Of these, 296 seats were allotted to British India and 93 seats to the Princely States. Out of 296 seats allotted to British India, 292 members were drawn from the eleven governors’ provinces 4 from the four chief commissioners’ provinces, and one from each.

- Each province and princely state were to be allotted seats in proportion to their respective population. Roughly one seat was to be allotted for every million population.

- Seats allocated to each British province were to be divided among Muslims, Sikhs, and General (others), in proportion to their population.

- The representatives of each community were to be elected by members of that community in the provincial legislative assembly and voting was to be by the method of proportional representation using a single transferable vote.

- The representatives of the princely states were to be nominated by the heads of the princely states.

Thus, under the above provisions, the Constituent Assembly became a partly elected and partly nominated body. The members were indirectly elected by the members of the provincial assemblies. It did not present the sentiments of the masses as the members of provincial assemblies themselves were elected on a limited franchise.

- The election for 296 seats allotted to the British Indian Provinces was held in July-August 1946. Out of these seats, the Indian National Congress won 208 seats, the Muslim League won 73 seats, and the remaining 15 seats were held by independent players.

- 93 seats allocated to princely states were not filled as they refrained from the Assembly.

- Though the assembly did not reflect the mass verdict it had representatives from every section of the society.

- Mahatma Gandhi was not a member of the Constituent Assembly.

Working of the Constituent Assembly

The Constituent Assembly held its first meeting on December 9, 1946. Muslim League boycotted the meeting and demanded a separate state of Pakistan. Only 211 members attended the first meeting.

Dr. Sachchidananda Sinha was elected as the temporary/interim President of the Assembly, following the French practice. Later Dr. Rajendra Prasad was elected as the President of the Assembly and both H.C. Mukherjee and V.T. Krishnamachari became the Vice-President of the Assembly.

Objective Resolution: On December 13, 1946, Jawahar Lal Nehru moved the ‘Objective Resolution’ in the Constituent Assembly which was unanimously adopted by the assembly on January 22, 1947.

The important provisions of the Resolution were:

- This Constituent Assembly declares its firm and solemn resolve to proclaim India as an Independent Sovereign Republic and to draw up for her future governance a Constitution.

- Wherein the territories comprising present-times British India, the territories that now form the Indian State and such other parts of India as are outside India and the States as well as other territories as are willing to be constituted into independent sovereign India, shall be a Union of them all

- Wherein the said territories, whether with their present boundaries or with such others as may be determined by the Constituent Assembly and thereafter according to the law of the Constitution, shall possess and retain with the residuary powers and exercise all powers and functions of the Government and administration implied in the Union or resulting therefrom

- Wherein all power and authority of Sovereign Independent India, its constituent parts and organs of Government are derived from the people.

- Wherein shall be guaranteed and secured to all the people of India justice, social, economic, and political; equality of status of opportunity, and before the law; freedom of thought, expression, belief, faith, worship, vocation, association, and action, subject to the law and public morality.

- Wherein adequate safeguards shall be provided for minorities, backward and tribal areas, and depressed and other backward classes.

- Whereby shall be maintained the integrity of the territory of the Republic and its sovereign rights on land, sea, and air according to justice and the law of civilized nations.

- This ancient land attains its rightful and honoured place in the world and makes its full and willing contribution to the promotion of world peace and the welfare of mankind.

Initially, the representatives of the princely states stayed away from the Constituent Assembly. On April 28, 1947 representatives of the 6 states became part of the assembly and after the acceptance of the Mountbatten Plan of June 3, 1947, most of the other princely states entered the assembly. Later the members of the Muslim League from the Indian dominion also joined the assembly.

Changes after the Indian Independence Act, of 1947: The act of 1947 made the following changes:

- The Assembly became the fully sovereign body and was empowered to frame any Constitution it pleased.

- It became the legislative body. It became responsible to frame the Constitution of India and enact ordinary laws for the country. Whenever the assembly worked as a Constitutional body, it was chaired by Dr. Rajendra Prasad and when it met as a legislative body, G.V. Mavlankar became the chairman (this arrangement continued till November 26, 1949).

- Muslim League withdrew from the assembly and it reduced the total strength of the assembly to 299 from 389. The strength of Indian provinces reduced to 229 from 296 and that of princely states to 70 from 93.

Other Functions performed by the Assembly:

- Ratified India’s membership of the Commonwealth in May 1949.

- Adopted the National Flag of India on July 22, 1947.

- Adopted National Anthem on January 24, 1950.

- Elected Dr Rajendra Prasad was the first President of India on January 24, 1950.

On January 24, 1950, the Constituent Assembly held its final session but continued as the provincial parliament from January 26, 1950, till the first general elections in 1951-52 were held.

Committees of the Constituent Assembly

Drafting Committee

On August 29, 1947, a Drafting Committee was set up to prepare a draft of the new Constitution. It was a seven-member committee with Dr. B.R. Ambedkar as the Chairman of the committee. The other 6 members include:

Members of the Drafting Committee

- N. Gopalaswamy Ayyangar

- Alladi Krishnaswamy Ayyar

- Dr. K.M. Munshi

- Syed Mohammad Saadullah

- N.M. Rau

- T.T. Krishnamachari

Enactment of the Constitution

- Dr. B.R. Ambedkar introduced the final draft of the Constitution in the Assembly on November 4, 1948, for the first reading. The second reading was held on November 15, 1948, and the third reading on November 14, 1949.

- The draft was passed on November 26, 1949 (thus, celebrated as Constitution day).

- The Constitution as adopted on November 26, 1949, contained the Preamble, 395 Articles, and 8 Schedules.

- Provisions of citizenship, elections, provisional parliament, temporary and transitional provisions, and short title are contained in Articles 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 60, 324, 366, 367, 379, 380, 388, 391, 392, and 393 came into force on November 26, 1949. The remaining provisions came into force on January 26, 1950.

- With the adoption of the Constitution, all the provisions under the Indian Independence Act, of 1947, and the Government of India Act, of 1935 were repealed.

- The Abolition of Privy Council Jurisdiction Act (1949) continued.

Enforcement of the Constitution

- The provisions of the Indian Constitution related to citizenship, elections, provisional parliament, temporary and transitional provisions, and short title, contained in Articles 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 60, 324, 366, 367, 379, 380, 388, 391, 392, and 393 came into force on November 26, 1949.

- The majority of the Constitution, excluding the mentioned provisions, came into force on January 26, 1950, celebrated as Republic Day. This date was chosen due to its historical significance, being the day of the Purna Swaraj celebration in 1930 after the resolution of the Lahore Session (December 1929) of the INC.

- The ‘date of commencement’ of the Constitution marks the celebration of Republic Day, and it symbolizes the culmination of the independence movement.

- The Indian Independence Act of 1947 and the Government of India Act of 1935, along with all enactments amending or supplementing the latter Act, were repealed with the commencement of the Constitution.

- The Abolition of Privy Council Jurisdiction Act (1949) was an exception and continued to be in effect after the Constitution came into force.

Experts Committee of the Congress

- Formation of the Experts Committee: On July 8, 1946, while Constituent Assembly elections were ongoing, the Congress Party (Indian National Congress) appointed an Experts Committee to prepare material for the Constituent Assembly.

- Committee Members: Jawaharlal Nehru served as the Chairman, and other members included M. Asaf Ali, K.M. Munshi, N. Gopalaswami Ayyangar, K.T. Shah, D.R. Gadgil, Humayun Kabir, and K. Santhanam.

- Additional Member and Convener: Krishna Kripalani was later co-opted as a member and the convener of the committee on the Chairman’s proposal.

- Committee Proceedings: The committee had two sittings: the first in New Delhi from July 20 to 22, 1946, and the second in Bombay from August 15 to 17, 1946.

- Discussion Topics: Apart from individual notes prepared by its members, the committee deliberated on the procedure to be adopted by the Constituent Assembly. They also discussed the appointment of various committees and drafted a resolution on the objectives of the constitution, to be presented during the first session of the Constituent Assembly.

- Role in Constitution Making: According to Granville Austin, an American constitutional expert, the Congress Experts Committee played a crucial role in shaping India’s constitution. They worked within the framework of the Cabinet Mission Scheme, providing general suggestions on autonomous areas, powers of provincial and central governments, princely states, and the amending power. The committee’s drafted resolution closely resembled the Objectives Resolution.

- Significance: The committee’s efforts were instrumental in setting the foundation for India’s constitution, guiding the early discussions and shaping key aspects within the constitutional framework.

Criticism of the Constituent Assembly

The Constituent Assembly was criticized on various grounds including:

- Not a Representative Body as it did not reflect the mass verdict due to election by the limited franchise.

- Not a Sovereign body as it was formed based on the proposals of the British Government and held its meetings with their permission.

- Took greater time to frame the Constitution as compared to the American Constitution which took only 4 months.

- Dominated by Congress

- The domination of Lawyers and Politicians and the representation of other professionals were not significant

- Dominated by Hindus

Do You Know!

- S.N. Mukherjee was the chief draftsman of the constitution in the Constituent Assembly.

- Prem Behari Narain Raizada was the calligrapher of the Indian Constitution. He had handwritten the original text of the constitution in a flowing italic style.

- It was beautified and decorated by artists from Shanti Niketan including Nand Lal Bose and Beohar Rammanohar Sinha.

- The calligraphy of the Hindi version of the original constitution was done by Vasant Krishan Vaidya and decorated and illuminated by Nand Lal Bose.

- The elephant was adopted as the symbol of the Constituent Assembly. Thus, its figurine was carved on the seal of the assembly.

- Originally, the Constitution of India did not make any provision concerning an authoritative text of the Constitution in the Hindi Language. Later, a provision in this regard was made by the 58th Constitutional Amendment Act of 1987 which inserted a new Article 394-A in the last part of the constitution.

In this document, you have learned that

- In 1935, the Indian National Congress for the first time demanded a Constituent Assembly to frame the Constitution of India.

- In November 1946, Constituent Assembly was constituted under the scheme formulated by the Cabinet Mission Plan.

- Muslim League withdrew from the assembly and it reduced the total strength of the assembly to 299 from 389. The strength of Indian provinces reduced to 229 from 296 and that of princely states to 70 from 93.

- Members of the Drafting Committee

- N. Gopalaswamy Ayyangar

- Alladi Krishnaswamy Ayyar

- Dr. K.M. Munshi

- Syed Mohammad Saadullah

- N.M. Rau

- T.T. Krishnamachari

- One of the main criticism of The Assembly was it being a domination of Lawyers and Politicians and representation of other professionals was not significant.

CH3. Salient Features of the Constitution

Introduction

The Indian Constitution is special because it takes ideas from around the world but still has its own unique qualities. Over time, there have been important changes, especially with the 42nd Amendment in 1976, which had a big impact on many parts of the Constitution. The courts, in a case called Kesavananda Bharati in 1973, said that while Parliament can make changes, it can’t touch the Constitution’s fundamental structure. So, despite these changes, the Constitution keeps its special identity, showing how it can adapt and grow while staying true to its core.

Salient Features of the Constitution

The Salient features of the constitution are as follows:

1. Lengthiest Written Constitution

- Constitutions are classified into written (like the American) or unwritten (like the British).

- Indian Constitution is the world’s lengthiest written constitution.

- Original (1949): Preamble, 395 Articles (22 Parts), 8 Schedules.

- Current: Preamble, about 470 Articles (25 Parts), 12 Schedules.

- Amendments since 1951: Deleted 20 Articles, one Part (VII), added 95 Articles, four Parts (IVA, IXA, IXB, XIVA), four Schedules (9, 10, 11, 12).

- Factors contributing to size: Geographical diversity, historical influence, single constitution for Center and states, legal luminaries’ dominance.

- Comprehensive content includes fundamental principles and detailed administrative provisions.

- Jammu and Kashmir had special status until 2019 (Article 370).

- Abolishment of special status in 2019, extending all provisions of the Constitution of India to Jammu and Kashmir.

- Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act, 2019, created two Union territories: Jammu & Kashmir and Ladakh.

2. Drawn From Various Sources

- The Constitution of India incorporates provisions from various countries and the Government of India Act of 1935.

- Dr. B.R. Ambedkar emphasized the exhaustive study of global constitutions during the framing.

- Structural elements, largely from the Government of India Act of 1935.

- Philosophical aspects (Fundamental Rights and Directive Principles) inspired by American and Irish Constitutions respectively.

- Political components (Cabinet Government principle, Executive-Legislature relations) drawn from British Constitutions.

- Other provisions borrowed from the constitutions of Canada, Australia, Germany, USSR (now Russia), France, South Africa, Japan, and more.

- The Government of India Act, 1935, holds significant influence, serving as a major source.

- Federal Scheme, Judiciary, Governors, Emergency Powers, Public Service Commissions, and administrative details mainly drawn from the 1935 Act.

- Over half of the Constitution’s provisions are identical or closely resemble those in the 1935 Act.

3. Blend of Rigidity and Flexibility

- Constitutions are classified as rigid or flexible.

- Rigid Constitution: Requires a special procedure for amendment (e.g., American Constitution).

- Flexible Constitution: Amended like ordinary laws (e.g., British Constitution).

- Indian Constitution: Neither rigid nor flexible, a synthesis of both.

- Article 368 outlines two types of amendments:

(a) Special majority of Parliament (two-thirds of members present and voting, and majority of total membership).

(b) Special majority of Parliament with ratification by half of the total states. - Some Constitution provisions are amendable by a simple majority in the manner of the ordinary legislative process.

- These amendments do not fall under Article 368.

4. Federal System with Unitary Bias

- Indian Constitution: Establishes a federal system of Government.

- Usual federal features include two Governments, division of powers, a written Constitution, supremacy, rigidity, an independent judiciary, and bicameralism.

- Unitary/non-federal features include a strong Center, single Constitution, single citizenship, flexibility, integrated judiciary, Center-appointed state governor, all-India services, emergency provisions, etc.

- Parliamentary government features:

- Federal in form but unitary in spirit.

- Described as ‘Union of States’ in Article 1.

- Implies the Indian Federation is not a result of a state agreement.

- No state has the right to secede from the federation.

- Descriptive terms for the Indian Constitution:

- ‘Quasi-federal’ by K.C. Wheare.

- ‘Bargaining federalism’ by Morris Jones.

- ‘Co-operative federalism’ by Granville Austin.

- ‘Federation with a centralizing tendency’ by Ivor Jennings.

5. Parliamentary Form of Government

- Constitution of India: Adopts the British Parliamentary System over the American Presidential System.

- The parliamentary system emphasizes cooperation between legislative and executive, contrary to the American separation of powers.

- Also known as ‘Westminster Model,’ ‘Responsible Government,’ and ‘Cabinet Government.’

- Features of Parliamentary Government in India:

- Presence of nominal and real executives.

- Majority party rule.

- Collective responsibility of the executive to the legislature.

- Membership of ministers in the legislature.

- Leadership of the Prime Minister or Chief Minister.

- Dissolution of the lower House (Lok Sabha or Assembly).

- Westminster: Symbol/synonym for the British Parliament.

- Differences from the British Parliamentary System:

- Indian Parliament is not sovereign, unlike the British.

- Indian State has an elected head (republic), while the British State has a hereditary head (monarchy).

- In both Indian and British parliamentary systems, the role of the Prime Minister is significant, termed as ‘Prime Ministerial Government.’

6. Synthesis of Parliamentary Sovereignty and Judicial Supremacy

- Sovereignty of Parliament:

- Associated with the British Parliament.

- Principle of judicial supremacy linked to the American Supreme Court.

- Judicial Review in India:

- Differs from the British system and is narrower than the U.S.

- American Constitution’s ‘due process of law’ vs. Indian Constitution’s ‘procedure established by law’ (Article 21).

- Indian Constitutional Synthesis:

- A balance between British parliamentary sovereignty and American judicial supremacy.

- Supreme Court can declare parliamentary laws unconstitutional through judicial review.

- Parliament can amend a major portion of the Constitution through its constituent power.

7. Integrated and Independent Judiciary

- Indian Judicial System: Integrated and independent.

- Hierarchy:

- Supreme Court: Apex of the integrated system.

- High Courts: At the state level.

- Subordinate Courts: Hierarchy includes district courts and lower courts.

- Enforcement of Laws:

- Single system of courts enforces both central and state laws.

- In the USA, federal laws by federal judiciary, state laws by state judiciary.

- Supreme Court’s Role: Federal court, highest appeal court, guardian of fundamental rights, and Constitution.

- Provisions for Independence:

- Security of tenure for judges.

- Fixed service conditions.

- Supreme Court expenses from Consolidated Fund of India.

- Prohibition on discussing judge conduct in legislatures.

- Ban on practice after retirement.

- Contempt of court power vested in the Supreme Court.

- Separation of judiciary from the executive.

8. Fundamental Rights

- Fundamental Rights in Indian Constitution (Part III):

- Right to Equality (Articles 14-18)

- Right to Freedom (Articles 19-22)

- Right against Exploitation (Articles 23-24)

- Right to Freedom of Religion (Articles 25-28)

- Cultural and Educational Rights (Articles 29-30)

- Right to Constitutional Remedies (Article 32)

- Original Fundamental Rights:

- Seven initially, with the Right to Property (Article 31).

- Removed by the 44th Amendment Act of 1978.

- Right to Property became a legal right under Article 300-A in Part XII.

- Purpose of Fundamental Rights:

- Promote political democracy.

- Limit executive tyranny and arbitrary laws.

- Enforceable by courts; justiciable in nature.

- Limitations on Fundamental Rights:

- Not absolute, subject to reasonable restrictions.

- Can be curtailed or repealed by Parliament through Constitutional Amendment Act.

- Suspended during National Emergency, except rights under Articles 20 and 21.

9. Directive Principles of State Policy

- Directive Principles of State Policy (Part IV):

- Termed a ‘novel feature’ by Dr. B.R. Ambedkar.

- Three categories: socialistic, Gandhian, liberal-intellectual.

- Purpose:

- Aim to promote social and economic democracy.

- Establish a ‘welfare state’ in India.

- Enforceability:

- Unlike Fundamental Rights, not justiciable.

- Not enforceable by courts for violation.

- Moral Obligation:

- Constitution declares them fundamental.

- State duty to apply these principles in making laws.

- Imposes a moral obligation on state authorities.

- Force Behind Principles:

- Political force, primarily public opinion.

- Not legally binding but carry moral weight.

- Minerva Mills Cases (1980): TheSupreme Court emphasized the balance between Fundamental Rights and Directive Principles in the Indian Constitution.

10. Fundamental Duties

- Fundamental Duties (Part IV-A):

- Not in the original constitution.

- Added during the internal emergency (1975-77) by the 42nd Constitutional Amendment Act of 1976.

- One more duty added by the 86th Constitutional Amendment Act of 2002.

- Specification:

- Part IV-A, Article 51-A lists eleven Fundamental Duties.

- Includes respecting the Constitution, national flag, and national anthem.

- Involves protecting the sovereignty, unity, and integrity of the country.

- Promotes common brotherhood and preserves the rich heritage of composite culture.

- Purpose of Fundamental Duties:

- Serve as a reminder to citizens about their responsibilities while enjoying rights.

- Consciousness of duties to country, society, and fellow citizens.

- Enforceability:

- Like Directive Principles, non-justiciable in nature.

- Not legally binding but highlight the moral and ethical responsibilities of citizens.

11. A Secular State

- Secular Character of the Indian State:

- The Constitution stands for a secular state, with no official religion.

- Provisions indicating secularism:

- ‘Secular’ was added to Preamble by the 42nd Amendment Act of 1976.

- The preamble ensures liberty of belief, faith, and worship for all citizens.

- Equality before the law and non-discrimination on the grounds of religion (Articles 14-15).

- Equality of opportunity in public employment (Article 16).

- Freedom of conscience and the right to profess, practice, and propagate any religion (Article 25).

- Right of religious denominations to manage their religious affairs (Article 26).

- No compelled taxes for promoting a particular religion (Article 27).

- No religious instruction in state-maintained educational institutions (Article 28).

- Right to conserve distinct language, script, or culture (Article 29).

- Minorities’ right to establish and administer educational institutions (Article 30).

- State’s endeavour for a Uniform Civil Code (Article 44).

- Indian Secularism:

- Positive concept: Equal respect and protection to all religions.

- Inapplicability of the Western concept of complete separation due to the multi-religious nature of Indian society.

- Abolishment of Communal Representation:

- Abolished old communal representation system.

- Temporary reservation of seats for scheduled castes and tribes for adequate representation.

12. Universal Adult Franchise

- Basis for Lok Sabha and state legislative assembly elections.

- Every citizen 18 years or older has the right to vote without discrimination.

- Voting Age: Reduced to 18 from 21 in 1989 by the 61st Constitutional Amendment Act of 1988.

- Bold Experiment:

- Constitution-makers introduced universal adult franchise.

- Remarkable considering vast size, huge population, high poverty, social inequality, and overwhelming illiteracy.

- Impact of Universal Adult Franchise:

- Broadens democracy, making it inclusive.

- Enhances self-respect and prestige of common people.

- Upholds the principle of equality.

- Enables minorities to protect their interests.

- Opens new opportunities for weaker sections.

13. Single Citizenship

- Indian Constitution and Citizenship:

- Federal structure with a dual polity (Centre and states).

- Provides for a single citizenship, i.e., Indian citizenship.

- Comparison with the USA:

- In the USA, individuals are citizens of both the country and the state they belong to.

- Dual allegiance and rights conferred by both the national and state governments.

- Indian Citizenship:

- All citizens, regardless of their state of birth or residence, enjoy the same political and civil rights throughout the country.

- No discrimination based on regional factors.

- Challenges despite Single Citizenship:

- Communal riots, class conflicts, caste wars, linguistic clashes, and ethnic disputes persist.

- The Constitution’s goal of building a united and integrated Indian nation not fully realized.

14. Independent Bodies

- Independent Bodies in the Indian Constitution:

- Complement legislative, executive, and judicial organs.

- Crucial for the democratic system in India.

- Election Commission: Ensures free and fair elections for Parliament, state legislatures, President, and Vice President.

- Comptroller and Auditor-General of India:

- Audits accounts of Central and state governments.

- Guardian of the public purse, comments on legality and propriety of government expenditure.

- Union Public Service Commission:

- Conducts examinations for recruitment to All-India services and higher Central services.

- Advises the President on disciplinary matters.

- State Public Service Commission:

- Every state conducts examinations for recruitment to state services.

- Advises the governor on disciplinary matters.

- Independence Assurance: The Constitution ensures independence through provisions like security of tenure, fixed service conditions, and expenses charged to the Consolidated Fund of India.

15. Emergency Provisions

- Emergency Provisions in the Indian Constitution: Included to safeguard sovereignty, unity, integrity, and security of the country, democratic political system, and the Constitution.

- Types of Emergencies:

- National Emergency (Article 352): Grounds: War, external aggression, armed rebellion.

- State Emergency (President’s Rule) (Article 356): Grounds: Failure of Constitutional machinery in states.

- Financial Emergency (Article 360): Grounds: Threat to financial stability or credit of India.

- Central Government’s Powers During Emergency:

- All-powerful during an emergency.

- States come under the total control of the Centre.

- Federal structure transforms into a unitary one without a formal constitutional amendment.

- Unique Feature of the Indian Constitution: Transformation from federal (normal times) to unitary (during emergencies) is distinctive and unique.

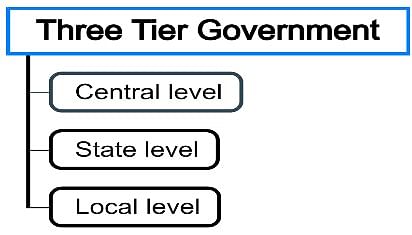

16. Three-tier Government

- Originally, the Indian Constitution focused on a dual polity—Centre and states, like other federal constitutions.

- Later, the 73rd Constitutional Amendment Act (1992) added a third tier of government, not present in other world constitutions.

- The 73rd Amendment recognized panchayats, adding Part IX and Schedule 11, instituting a three-tier panchayati raj system in every state.

- The 74th Constitutional Amendment Act (1992) added Part IX-A and Schedule 12, recognizing municipalities and introducing three types in every state—nagar panchayat, municipal council, and municipal corporation.

17. Co-operative Societies

The 97th Constitutional Amendment Act of 2011 conferred constitutional status and protection to co-operative societies, bringing about three key changes:

- Elevated the formation of co-operative societies to a fundamental right under Article 19.

- Introduced a new Directive Principle of State Policy focused on the promotion of cooperative societies (Article 43-B).

- Added a new section, Part IX-B, titled “The Co-operative Societies” (Articles 243-ZH to 243-ZT), containing provisions to ensure the democratic, professional, autonomous, and economically sound functioning of co-operative societies. Empowers Parliament and state legislatures to legislate appropriately for multi-state and other cooperative societies, respectively.

Criticism of the Constitution

The Constitution of India, as framed and adopted by the Constituent Assembly of India, has been criticized on the following grounds:

1. A Borrowed Constitution

- Labelled as a ‘borrowed Constitution,’ ‘bag of borrowings,’ ‘hotch-potch Constitution,’ or ‘patchwork’ of world constitutions by critics.

- Critics argue that it lacks originality.

- Critics’ views are deemed unfair and illogical.

- Framers made necessary modifications to borrowed features, adapting them to Indian conditions and avoiding faults.

- Dr. B.R. Ambedkar defended the Constitution in the Constituent Assembly.

- Highlighted the inevitability of similarities in main provisions among constitutions globally.

- Stressed that variations to address faults and accommodate national needs are the only novel aspects.

- Dismissed the charge of blindly copying other countries’ constitutions as based on inadequate study.

2. A Carbon Copy of the 1935 Act

- Critics: Raised concerns about extensive borrowing from the Government of India Act of 1935.

- “Carbon Copy” and “Amended Version”: Terms used by critics to characterize the Constitution’s relationship with the 1935 Act.

- N. Srinivasan: Described the Constitution as closely resembling the 1935 Act in language and substance.

- Sir Ivor Jennings: Noted direct derivations and textual similarities between the Constitution and the 1935 Act.

- P.R. Deshmukh: Commented that the Constitution added adult franchise to the 1935 Act.

- Dr. B.R. Ambedkar: Defended the borrowing, emphasizing that fundamental constitutional ideas are not patentable.

- Administrative Details: Dr. Ambedkar expressed regret that the borrowed provisions mainly related to administrative details.

3. Un-Indian or Anti-Indian

- Described the Indian Constitution as ‘un-Indian’ or ‘anti-Indian.’

- Claimed that it does not align with India’s political traditions and spirit.

- K. Hanumanthaiya: Expressed dissatisfaction, comparing the desired music of Veena or Sitar to the perceived English band music in the Constitution.

- Lokanath Misra: Criticized the Constitution as a “slavish imitation of the west” and a “slavish surrender to the west.”

- Lakshminarayan Sahu:

- Observed that the ideals in the draft Constitution lacked a manifest relation to the fundamental spirit of India.

- Predicted that the Constitution would not be suitable and would break down soon after implementation.

4. An Un-Gandhian Constitution

- Labelled the Indian Constitution as un-Gandhian.

- Argued that it lacks Mahatma Gandhi’s philosophy and ideals.

- K. Hanumanthaiya: Stated that the Constitution was not in line with what Mahatma Gandhi wanted or envisaged.

- T. Prakasam: Attributed the perceived lapse to Ambedkar’s non-participation in the Gandhian movement and his antagonism towards Gandhian ideas.

5. Elephantine Size

- Described the Indian Constitution as too bulky and detailed.

- Sir Ivor Jennings suggested that the borrowed provisions were not always well-selected.

- H.V. Kamath:

- Compared the constitution to an elephant, symbolizing its bulkiness.

- Urged against making the Constitution overly extensive.

6. Paradise of the Lawyers

- Described the Indian Constitution as too legalistic and complicated.

- Sir Ivor Jennings labeled it a “lawyer’s paradise.”

- H.K. Maheswari: Suggested that the legal language might lead to increased litigation.

- P.R. Deshmukh:

- Criticized the draft for being too ponderous, resembling a law manual.

- Desired a more dynamic and concise socio-political document.

CH4. Preamble of the Constitution

The American Constitution was the first to begin with a Preamble. The Preamble to the Indian Constitution is based on the “Objectives Resolution’, drafted and moved by Pandit Nehru, and adopted by the Constituent Assembly. It has been amended by the 42nd Constitutional Amendment Act t.1976), which added three new words – socialist, secular and integrity.

TEXT OF THE PREAMBLE: The Preamble in its present form reads:

“ We, THE PEOPLE OF INDIA, having solemnly resolved to constitute India into a SOVEREIGN SOCIALIST SECULAR DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC and to secure to all its citizens: JUSTICE’, Social, Economic and Political; LIBERTY of thought, expression, belief, faith and worship; EQUALITY of status and of opportunity; and to promote among them all; FRATERNITY assuring the dignity of the individual and the unity and integrity of the Nation;

IN OUR CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY this twenty-sixth day of November, 1949, do HEREBY ADOPT, ENACT AND GIVE TO OURSELVES THIS CONSTITUTION”

KEY WORDS IN THE PREAMBLE

Certain key words—Sovereign, Socialist, Secular, Democratic, Republic, Justice, Liberty, Equality and Fraternity—are explained as follows:

Sovereign

- The word “sovereign’ implies that India is neither a dependency nor a dominion of any other nation, but an independent state.

- There is no authority above it, and it is free to conduct its own affairs (both internal and external).

Socialist

- Even before the term was added by the 42nd Amendment in 1976, the Constitution had a socialist content in the form of certain Directive Principles of State Policy.

- Democratic socialism, on the other hand, holds faith in a “mixed economy’ where both public and private sectors co-exist side by side. As the Supreme Court says, ‘Democratic socialism aims to end poverty, ignorance, disease and inequality of opportunity.

Secular

- The term “secular’ too was added by the 42nd Constitutional Amendment Act of 1976. However, as the Supreme Court said in 1974, although the words “secular state’ were not expressedly mentioned in the Constitution, there can be no doubt that Constitution-makers wanted to establish such a state and accordingly Articles 25 to 28 (guaranteeing the fundamental right to freedom of religion) have been included in the constitution.

- The Indian Constitution all religions in our country have the same status and support from the state.

Democratic

- A democratic polity, as stipulated in the Preamble, is based on the doctrine of popular sovereignty, that is, possession of supreme power by the people.

- Democracy is of two types-direct and indirect. In direct democracy, the people exercise their supreme power directly as is the case in Switzerland. There are four devices of direct democracy, namely, Referendum, Initiative, Recall and Plebiscite.

- In indirect democracy, on the other hand, the representatives elected by the people exercise the supreme power and thus carry on the government and make the laws. This type of democracy, also known as representative democracy, is of two kinds-parliamentary and presidential.

- The term ‘democratic’ is used in the Preamble in the broader senseembracing not only political democracy but also social and economic democracy.

Republic

- The term ‘republic’ in our Preamble indicates that India has an elected head called the president. He is elected indirectly for a fixed period of five years.

- A republic also means two more things: one, vesting of political sovereignty in the people and not in a single individual like a king; second, the absence of any privileged class and hence all public offices being opened to every citizen without any discrimination.

Objectives of Indian State

- Justice : Social, Economic and Political.

- Liberty : of thought, expression, belief, faith and worship.

- Equality : of status and opportunity, and to promote among them all.

- Fraternity : (=Brotherhood) : assuring the dignity of the individual and the unity and integrity of the nation.

1. Justice: Social, Economic, and Political

The objective of ensuring justice in Indian society is to create a fair, impartial, and equal system for all citizens. Social justice aims to provide equal opportunities and treatment to all individuals, regardless of their caste, religion, gender, or economic status. Economic justice focuses on providing equal opportunities for all citizens to participate in the economy and enjoy the benefits of economic growth. Lastly, political justice ensures that all citizens have the right to participate in the political process and decision-making, as well as equal protection under the law.

2. Liberty: of thought, expression, belief, faith, and worship

The Indian state aims to guarantee the freedom of thought, expression, belief, faith, and worship to all its citizens. This objective promotes a diverse and tolerant society where individuals have the right to express their opinions, practice their religion, and follow their beliefs without fear of discrimination or persecution. By ensuring these liberties, the Indian state fosters an environment in which the free exchange of ideas and knowledge can flourish, contributing to the nation’s progress.

3. Equality: of status and opportunity, and to promote among them all

The objective of equality in the Indian state focuses on providing equal status and opportunities to all citizens, regardless of their social, economic, or cultural background. This means that all individuals should have equal access to resources, education, and employment, and that discrimination based on caste, religion, gender, or economic status should be eliminated. The Indian state works to promote policies and programs that address inequalities and provide support to marginalized communities to ensure that they have equal opportunities to succeed.

4. Fraternity (Brotherhood): assuring the dignity of the individual and the unity and integrity of the nation

The objective of fraternity in the Indian state is to create a sense of unity among the diverse population while maintaining the dignity of each individual. By promoting brotherhood and understanding among its citizens, the Indian state fosters social cohesion and ensures that the nation remains unified in its pursuit of progress. This objective also emphasizes the importance of respecting each individual’s dignity and rights, which contributes to a harmonious and inclusive society.

PREAMBLE AS PART OF THE CONSTITUTION

- In the Berubari Union case (1960), the Supreme Court said that the Preamble shows the general purposes behind the several provisions in the Constitution, the Supreme Court specifically opined that Preamble is not a part of the Constitution.

- In the Kesavananda Bharati case 17 (1973), the Supreme Court rejected the earlier opinion and held that Preamble is a part of the Constitution.

- In the LIC of India case(1995) also, the Supreme Court again held that the Preamble is an integral part of the Constitution. Like any other part of the Constitution.

- However, two things should be noted

- The Preamble is neither a source of power to legislature nor a prohibition upon the powers of legislature.

- It is non-justiciable, that is, its provisions are not enforceable in courts of law.

AMENDABILITY OF THE PREAMBLE

Preamble can be amended under Article 368 of the Constitution arose for the first time in the historic case of Kesavananda Bharati (1973). The Preamble has been amended only once so far, in 1976, by the 42nd Constitutional Amendment Act, which has added three new words Socialist, Secular and Integrity to the Preamble. This amendment was held to be valid.

CH5. Union and its Territory

Part 1 of the Indian Constitution

Part I of the Indian Constitution is titled The Union and its Territory.

- It includes articles from 1- 4.

- Part I is a compilation of laws pertaining to the constitution of India as a country and the union of states that it is made of.

- This part of the constitution contains the law in the establishment, renaming, merging, or altering of the borders of the states.

- Articles under Part I were invoked when West Bengal was renamed, and for the formation of relatively new states such as Jharkhand, Chattisgarh, or Telangana.

The Union and its Territory

Articles 1 to 4 under Part-I of the Constitution deal with the Union and its territory.

Article 1

Article 1 deals with the Name and territory of the Union

- India, that is Bharat, shall be a Union of States.

- The States and the territories thereof shall be as specified in the First Schedule.

- The territory of India shall comprise – the territories of the States; the Union territories specified in the First Schedule; and Such other territories as may be acquired.

Article 2

Article 2 deals with admission or establishment of new States.

- Parliament may by law admit into the Union, or establish, new States on such terms and conditions as it thinks fit.

- Article 2 grants two powers to the Parliament:

- the power to admit into the Union of India new states

the power to establish new states.

Article 3

Formation Of New States And Alteration Of Areas, Boundaries Or names Of Existing State.

Parliament may by law:

- form a new State by separation of territory from any State or by uniting two or more States or parts of States or by uniting any territory to a part of any State;

- increase the area of any State

- diminish the area of any State

- alter the boundaries of any State

- alter the name of any State.

Article 3 notably relates to the formation of or changes in the existing states of the Union of India.

However, Article 3 lays down two conditions in this regard:

- One, a bill contemplating the above changes can be introduced in the Parliament only with the prior recommendation of the President; and

- Two, before recommending the bill, the President has to refer the same to the state legislature concerned for expressing its views within a specified period.

- The President (or Parliament) is not bound by the views of the state legislature and may either accept or reject them, even if the views are received in time.

- Further, it is not necessary to make a fresh reference to the state legislature every time an amendment to the bill is moved and accepted in Parliament.

- In the case of a union territory, no reference need be made to the concerned legislature to ascertain its views and the Parliament can itself take any action as it deems fit.

Article 4

Article 4: declares that laws made under Article 2 and 3 are not to be considered as amendments of the Constitution under Article 368

- Article 4 declares that laws made for admission or establishment of new states (under Article 2) and formation of new states and alteration of areas, boundaries, or names of existing states (under Articles 3) are not to be considered as amendments of the Constitution under Article 368.

This means that such laws can be passed by a simple majority and by the ordinary legislative process.

The Supreme Court held that the power of Parliament to diminish the area of a state (under Article 3).

Dhar Commission and JVP Committee

- There has been a demand from different regions, particularly South India, for the reorganization of states on a linguistic basis.

- Accordingly, in June 1948, the Government of India appointed the Linguistic Provinces Commission under the chairmanship of S K Dhar to examine the feasibility of this.

South Indian States prior to the States Reorganisation Act.

South Indian States prior to the States Reorganisation Act.

- The commission submitted its report in December 1948 and recommended the reorganization of states on the basis of administrative convenience rather than linguistic factors. This created much resentment and led to the appointment of another Linguistic Provinces Committee by the Congress in December 1948 itself to examine the whole question afresh. It consisted of Jawaharlal Nehru, Vallahbhai Patel, and Pattabhi Sitaramayya and hence was popularly known as JVP Committee.

- It submitted its report in April 1949 and formally rejected language as the basis for the reorganization of states. However, in October 1953, the Government of India was forced to create the first linguistic state, known as Andhra state.

Fazl Ali Commission

- The creation of the Andhra state intensified the demand from other regions for the creation of states on a linguistic basis.

- This forced the Government of India to appoint (in December 1953) a three-member States. Reorganisation Commission under the chairmanship of Fazl Ali to re-examine the whole question.

- Its other two members were K M Panikkar and H N Kunzru.

It identified four major factors that can be taken into account in any scheme of reorganization of states:

- Preservation and strengthening of the unity and security of the country.

- Linguistic and cultural homogeneity.

- Financial, economic, and administrative considerations.

- Planning and promotion of the welfare of the people in each state as well as of the nation as a whole.

CH6. Citizenship

Meaning and Significance

- In India, there are two categories of people: citizens and aliens, with citizens being full members of the Indian State and enjoying all civil and political rights.

- Aliens, citizens of other countries, do not have all the civil and political rights enjoyed by citizens. They are classified as friendly aliens or enemy aliens based on their country’s relationship with India.

- Friendly aliens are citizens of nations with cordial relations with India, while enemy aliens are citizens of nations at war with India, enjoying lesser rights.

- Citizens in India have various rights and privileges guaranteed by the Constitution, including:

(i) Right against discrimination based on religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth (Article 15).

(ii) Right to equality of opportunity in public employment (Article 16).

(iii) Right to freedom of speech, expression, assembly, association, movement, residence, and profession (Article 19).

(iv) Cultural and educational rights (Articles 29 and 30).

(v) Right to vote in elections to the Lok Sabha and state legislative assembly.

(vi) Right to contest for membership of Parliament and state legislature.

(vii) Eligibility to hold certain public offices such as President, Vice-President, judges of the Supreme Court and high courts, Governor of states, Attorney General, and Advocate General. - Citizens also have duties towards the Indian State, including paying taxes, respecting national symbols, and defending the country.

- Both citizens by birth and naturalized citizens are eligible for the office of President in India, unlike the USA where only citizens by birth are eligible for the presidency.

Single Citizenship

- The Indian Constitution is federal, with a dual polity comprising the Centre and states, but it only provides for single citizenship, which is Indian citizenship.

- In contrast to countries like the USA and Australia, where double citizenship exists, Indian citizens owe allegiance solely to the Union, with no separate state citizenship.

- Double citizenship creates issues of discrimination, as states may favor their citizens in various matters such as voting rights, holding public offices, and professional opportunities.

- India’s system of single citizenship ensures uniform political and civil rights for all citizens across the country, without discrimination based on their state of birth or residence.

- Exceptions to the absence of discrimination include provisions allowing Parliament to prescribe residence as a condition for certain employments and states to provide benefits or preferences to their residents in matters not covered by constitutional rights.

- Article 19 protects the freedom of movement and residence but restricts outsiders’ rights to settle in tribal areas to safeguard the interests of scheduled tribes and protect their culture and property.

- Until 2019, Jammu and Kashmir had special provisions defining permanent residents and conferring specific rights and privileges on them, based on Article 35-A. However, this special status was abolished in 2019.

- The Constitution aims to promote fraternity and unity among Indians by introducing single citizenship and providing uniform rights, but India continues to face communal riots, class conflicts, caste wars, linguistic clashes, and ethnic disputes, indicating that the goal of building a fully integrated Indian nation has not been fully realized.

Constitutional Provisions

- The Constitution addresses citizenship from Articles 5 to 11 in Part 11, but it lacks permanent or detailed provisions regarding acquisition or loss of citizenship after its commencement.

- It identifies four categories of individuals who became citizens of India on January 26, 1950:

(i) Individuals with domicile in India who met specific conditions related to birth or residency.

(ii) Those who migrated to India from Pakistan and met residency requirements or were registered as citizens.

(iii) Individuals who migrated to Pakistan from India but later returned and met residency criteria.

(iv) Persons of Indian origin residing abroad who could register as Indian citizens through diplomatic or consular representatives. - These provisions cover citizenship for those domiciled in India, migrants from Pakistan, return migrants, and overseas Indians.

- Other constitutional provisions include:

(i) Prohibition on acquiring foreign citizenship voluntarily while remaining an Indian citizen.

(ii) Continuation of Indian citizenship for those already holding it, subject to parliamentary laws.

(iii) Parliament’s authority to enact laws concerning citizenship acquisition, termination, and related matters.

Citizenship Act, 1955

- The Citizenship Act (1955) governs the rules for acquiring and losing citizenship after the Constitution’s commencement.

- Initially, the act included provisions for Commonwealth Citizenship, but these were repealed in 2003.

Acquisition of Citizenship

(A) By Birth

- Individuals born in India between January 26, 1950, and July 1, 1987, are citizens regardless of their parents’ nationality.

- Different criteria apply to those born after July 1, 1987, and December 3, 2004.

- Children born to foreign diplomats or enemy aliens in India cannot acquire citizenship by birth.

(B) By Descent

- Citizenship can be acquired by individuals born outside India based on their father’s citizenship.

- The criteria and registration requirements vary depending on specific dates.

(C) By Registration

- The Central Government can register individuals meeting certain criteria, such as Indian origin or marriage to an Indian citizen.

- Registration provisions also apply to minor children of Indian citizens.

(C) By Naturalisation

- The Central Government may grant citizenship through naturalisation under specific qualifications and conditions.

- Recent amendments have reduced residency requirements for certain communities.

(D) By Incorporation of Territory

- When foreign territory becomes part of India, citizenship is granted to specified individuals from that territory.

- An example includes the Citizenship (Pondicherry) Order (1962) for Pondicherry’s incorporation.

(E) Special Provisions

- Assam Accord and Migrants: Special provisions apply to persons covered by the Assam Accord, granting citizenship based on residency and registration.

- Migrants from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, or Pakistan:

(i) Recent amendments allow citizenship for migrants belonging to specified communities who entered India before December 31, 2014.

(ii) Exemptions from certain penal consequences and eligibility for long-term visas were granted before the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019.

Loss of Citizenship

(A) By Renunciation:

- Citizens can voluntarily renounce their citizenship, leading to its termination.

- Exceptions exist during wartime.

(B) By Termination:

- Citizenship automatically terminates if a citizen voluntarily acquires citizenship of another country.

- Exceptions exist during wartime.

(C) By Deprivation:

- The Central government can compulsorily terminate citizenship for various reasons, including fraud, disloyalty, unlawful communication with enemies, imprisonment, or continuous residency outside India for seven years.

Overseas Citizenship of India

- In September 2000, the Indian Government established a High-Level Committee on the Indian Diaspora chaired by L.M. Singhvi.

- The committee aimed to study the global Indian diaspora comprehensively and propose measures for a constructive relationship.

- It recommended amending the Citizenship Act (1955) to grant dual citizenship to Persons of Indian Origin (PIOs) from certain countries.

L.M. Singhvi - The Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2003, allowed PIOs from 16 specified countries (excluding Pakistan and Bangladesh) to acquire Overseas Citizenship of India (OCI).

- The act also removed provisions related to Commonwealth Citizenship from the Principal Act.

- The Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2005, expanded OCI eligibility for PIOs from all countries allowing dual citizenship under their laws.

- The OCI is not technically dual citizenship due to constitutional restrictions.

- The Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2015, merged the PIO card scheme and OCI card scheme into a single “Overseas Citizen of India Cardholder” scheme.

- This was done to address confusion and enhance facilities for applicants.

- The PIO scheme was terminated on January 9, 2015, and all existing PIO cardholders were considered OCI cardholders from that date.

The Citizenship (Amendment) Act of 2015 introduced a change in terminology, substituting “Overseas Citizen of India” with “Overseas Citizen of India Cardholder,” and included the following provisions in the Principal Act:

Registration of Overseas Citizen of India Cardholder

The Central Government may register individuals as overseas citizens of India cardholders if they meet certain criteria:

- Individuals who were Indian citizens at the time of or after the commencement of the Constitution, or were eligible for Indian citizenship at that time.

- Individuals who were citizens of another country but belonged to a territory that became part of India after August 15, 1947.

- Minor children of eligible individuals, or individuals whose both parents are Indian citizens or one parent is an Indian citizen.

- Spouses of foreign origin of Indian citizens or overseas citizens of India cardholders, provided their marriage has been registered for at least two years.

- However, individuals or their ancestors from Pakistan, Bangladesh, or specified countries are not eligible for registration.

Conferment of Rights on Overseas Citizen of India Cardholder

- Overseas citizen of India cardholders are entitled to certain rights as specified by the Central Government.

- They are not entitled to certain rights granted to Indian citizens, such as equality of opportunity in public employment, eligibility for certain political positions, registration as a voter, or membership in legislative bodies.

Renunciation of Overseas Citizen of India Card

- Cardholders have the option to renounce their overseas citizen status by making a declaration.

- Once the declaration is registered by the Central Government, the individual ceases to be an overseas citizen of India cardholder.

- Additionally, the spouse and minor children of the cardholder also lose their overseas citizen status upon renunciation.

Cancellation of Registration as Overseas Citizen of India Cardholder:

- The Central Government has the authority to cancel the registration of a person as an overseas citizen of India cardholder under various circumstances.

- These circumstances include obtaining registration through fraudulent means, showing disaffection towards the Indian Constitution, engaging in unlawful activities during wartime, violating citizenship laws, imprisonment, or actions deemed against national security or public welfare.

- Before cancellation, the individual has the right to be heard, as per the provisions added by the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019.

CH7. Fundamental Rights

Introduction

Part III of the Constitution is rightly described as the Magna Carta of India. It contains a very long and comprehensive list of ‘justiciable’ Fundamental Rights. In fact, the Fundamental Rights in our Constitution are more elaborate than those found in the Constitution of any other country in the world, including the USA. Originally, the Constitution provided for seven Fundamental Rights via,

- Right to equality (Articles 14-18)

- Right to freedom (Articles 19-22)

- Right against exploitation (Articles 23-24)

- Right to freedom of religion (Articles 25-28)

- Cultural and educational rights (Articles 29-30)

- Right to property (Article 31)

- Right to constitutional remedies (Article 32) However, the right to property was deleted from the list of Fundamental Rights by the 44th Amendment Act, 1978. It is made a legal right under Article 300-A in Part XII of the Constitution. So at present, there are only six Fundamental Rights.

Article 12 (Definition Of State)

Article 12 of the Indian Constitution defines The State as:

- The Government and Parliament of India,

- The Government and legislatures of the states,

- All local authorities and

- Other authorities in India or under the control of the Government of India.

Article 13 (Laws Inconsistent With Fundamental Rights)

Article 13 of the Indian Constitution states that:

- All laws in force in the territory of India immediately before the commencement of this Constitution, in so far as they are inconsistent with the provisions of this Part, shall, to the extent of such inconsistency, be void.

- The State shall not make any law which takes away or abridges the rights conferred by this Part and any law made in contravention of this clause shall, to the extent of the contravention, be void.

- In this article, unless the context otherwise required,

(a) “law” includes any Ordinance, order, bye-law, rule, regulation, notification, custom or usage having in the territory of India the force of law;