So Close Yet So Different

Chapter – 1

THE ECONOMICS OF THE RIO GRANDE

- The city of Nogales is divided by a fence.

- Nogales, Arizona, is in Santa Cruz County.

- Average household income in Nogales, Arizona: ~$30,000/year.

- Most teenagers in Nogales, Arizona, attend school.

- Majority of adults in Nogales, Arizona, are high school graduates.

- Residents of Nogales, Arizona, have relatively high life expectancy.

- Many residents over 65 have access to Medicare.

- Government services in Nogales, Arizona: electricity, telephones, sewage system, public health, road network, law and order.

- Residents of Nogales, Arizona, feel safe and secure in their daily activities.

- Government in Nogales, Arizona, is seen as a public agent with democratic processes.

- Residents can vote for mayor, congressmen, senators, and in presidential elections.

- Democracy is deeply ingrained in Nogales, Arizona.

- Nogales, Sonora, is a relatively prosperous part of Mexico.

- Average household income in Nogales, Sonora: ~one-third of Nogales, Arizona.

- Most adults in Nogales, Sonora, lack a high school degree.

- Many teenagers in Nogales, Sonora, are not in school.

- High rates of infant mortality concern mothers in Nogales, Sonora.

- Poor public health conditions in Nogales, Sonora.

- Lower life expectancy in Nogales, Sonora, compared to Nogales, Arizona.

- Lack of public amenities in Nogales, Sonora.

- Poor road conditions in Nogales, Sonora.

- High crime rates in Nogales, Sonora.

- Opening a business in Nogales, Sonora, involves risk and bureaucratic challenges.

- Corruption and ineptitude among politicians are daily realities in Nogales, Sonora.

- Democracy is a recent experience in Nogales, Sonora.

- Before 2000, Nogales, Sonora, was under the control of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI).

- No difference in geography or climate between Nogales, Arizona, and Nogales, Sonora.

- Similar backgrounds of residents on both sides of the border.

- The area was part of the Mexican state of Vieja California before the Mexican-American War.

- The U.S. border extended into this area after the Gadsden Purchase of 1853.

- The two cities rose up on either side of the border, sharing ancestors, food, music, and culture.

- The differences between the two halves of Nogales are primarily due to the border.

- Nogales, Arizona, is part of the United States.

- Inhabitants of Nogales, Arizona, benefit from U.S. economic institutions.

- These institutions allow freedom in occupation choice and access to education and skills.

- Employers in Nogales, Arizona, invest in advanced technology, leading to higher wages.

- Political institutions in Nogales, Arizona, enable democratic participation.

- Residents can elect and replace their representatives if needed.

- Politicians in Nogales, Arizona, provide basic services demanded by citizens, including public health, roads, and law and order.

- Nogales, Sonora, residents do not have the same access to beneficial institutions.

- Different institutions in Nogales, Sonora, create disparate incentives compared to Nogales, Arizona.

- The institutions and incentives impact the economic prosperity of the two Nogaleses.

- U.S. institutions are more conducive to economic success than those of Mexico and Latin America.

- This difference is rooted in the formation of societies during the early colonial period.

- An institutional divergence occurred during colonization, with lasting effects.

- Understanding this divergence requires examining the foundation of North and Latin American colonies.

THE FOUNDING OF BUENOS AIRES

- In early 1516, Spanish navigator Juan Díaz de Solís sailed into a wide estuary on South America’s Eastern Seaboard.

- De Solís claimed the land for Spain, naming the river Río de la Plata due to the local people’s possession of silver.

- Indigenous peoples, the Charrúas in present-day Uruguay and the Querandí in modern Argentina, were hostile toward the newcomers.

- The Charrúas, a band of hunter-gatherers without centralized political authority, clubbed de Solís to death during his exploration.

- In 1534, Spain sent a mission of settlers led by Pedro de Mendoza to found a town on the site of Buenos Aires.

- Buenos Aires, meaning “good airs,” had a hospitable climate but did not meet Spanish expectations for resources and labor.

- The Charrúas and Querandí refused to provide food or labor and attacked the Spanish settlement.

- The Spaniards struggled with hunger as they did not anticipate providing food for themselves.

- Lacking silver or gold and unable to coerce the local population, the Spaniards sought richer lands and more compliant labor forces.

- In 1537, an expedition led by Juan de Ayolas went up the Paraná River, seeking a route to the Inca state.

- The expedition encountered the Guaraní, a sedentary agricultural people growing maize and cassava.

- After overcoming Guaraní resistance, the Spanish founded Nuestra Señora de Santa María de la Asunción, now Paraguay’s capital.

- The Spanish married Guaraní princesses and established themselves as a new aristocracy, adapting existing forced labor and tribute systems.

- Within four years, Buenos Aires was abandoned as settlers moved to the new town in Paraguay.

- Buenos Aires, later known as the “Paris of South America,” was resettled in 1580 and developed European-style boulevards and agricultural wealth.

- The early abandonment of Buenos Aires and conquest of the Guaraní illustrate the logic of European colonization.

- Spanish and English colonists sought not to till the soil themselves but to have others do it and to plunder riches, gold, and silver

FROM CAJAMARCA …

- The expeditions of de Solís, de Mendoza, and de Ayolas followed Christopher Columbus’s sighting of the Bahamas on October 12, 1492.

- Spanish expansion and colonization began earnestly with Hernán Cortés’s invasion of Mexico in 1519.

- Francisco Pizarro’s expedition to Peru occurred a decade and a half later.

- Pedro de Mendoza’s expedition to the Río de la Plata happened just two years after Pizarro’s.

- Over the next century, Spain conquered and colonized most of central, western, and southern South America.

- Portugal claimed Brazil to the east.

- The Spanish colonization strategy, first perfected by Cortés, involved capturing indigenous leaders to subdue opposition.

- This strategy allowed the Spanish to claim the leader’s wealth and coerce tribute and food from indigenous peoples.

- The Spanish then established themselves as the new elite, controlling existing taxation, tribute, and forced labor systems.

- When Cortés and his men arrived at the Aztec capital Tenochtitlan on November 8, 1519, they were welcomed by Moctezuma, the Aztec emperor.

- Despite advice from his counselors, Moctezuma decided to welcome the Spaniards peacefully.

- The Franciscan priest Bernardino de Sahagún’s Florentine Codices provide an account of what happened next:

- The Spanish seized Moctezuma and fired their guns, causing fear and terror among the people.

- Moctezuma commanded his people to provide the Spaniards with white tortillas, roasted turkey hens, eggs, fresh water, wood, firewood, and charcoal.

- The Spaniards, settled in the city, inquired about the city’s treasure, leading Moctezuma to guide them.

- They brought forth treasures from the storehouse called Teocalco, including quetzal feather head fans, devices, shields, golden discs, golden nose crescents, golden leg bands, golden arm bands, and golden forehead bands.

- The Spaniards set fire to precious items and formed the gold into separate bars.

- The Spaniards took everything valuable they found.

- They went to Moctezuma’s own storehouse at Totocalco and seized his personal property, including necklaces, arm bands with tufts of quetzal feathers, golden arm bands, bracelets, golden bands with shells, and the turquoise diadem.

- The Spanish took all of Moctezuma’s treasures.

- The military conquest of the Aztecs was completed by 1521.

- Hernán Cortés, as governor of New Spain, began dividing the indigenous population through the encomienda system.

- The encomienda, originating in fifteenth-century Spain during the reconquest from the Moors, took a more pernicious form in the New World.

- The encomienda was a grant of indigenous peoples to a Spaniard, known as the encomendero.

- Indigenous peoples had to provide tribute and labor services to the encomendero in exchange for being converted to Christianity.

- Bartolomé de las Casas, a Dominican priest, provided a vivid early account of the encomienda system.

- De las Casas arrived in Hispaniola in 1502 with Governor Nicolás de Ovando.

- He became disillusioned by the cruel and exploitative treatment of indigenous peoples.

- In 1513, De las Casas participated as a chaplain in the Spanish conquest of Cuba and was granted an encomienda for his service.

- He renounced the encomienda grant and campaigned to reform Spanish colonial institutions.

- His book, A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies, written in 1542, was a withering critique of Spanish rule.

- De las Casas described the encomienda system in Nicaragua:

- Settlers took residence in allotted towns and made the inhabitants work for them.

- They stole scarce foodstuffs from the indigenous people and took over their lands.

- The settlers treated the entire native population, including dignitaries, old men, women, and children, as members of their households.

- Indigenous people were forced to labor night and day without rest for the settlers’ interests.

- Bartolomé de las Casas reported on the conquest of New Granada, modern Colombia, demonstrating the Spanish strategy:

- Spaniards apportioned towns and their inhabitants among themselves, treating them as common slaves.

- The overall commander seized King Bogotá, holding him prisoner for six to seven months, demanding gold and emeralds.

- Terrified, King Bogotá promised to fill an entire house with gold to gain his freedom, sending his people to gather gold and precious stones.

- The Spaniards, unsatisfied with the collected amount, declared they would execute him for breaking his promise.

- The commander staged a mock trial, sentencing the king to torture unless he produced more gold.

- The king was subjected to the strappado, burning tallow on his belly, and iron hoops on his legs and neck.

- Two men held his hands while they burned the soles of his feet.

- The commander repeatedly threatened slow torture unless more gold was produced.

- King Bogotá eventually died from the tortures inflicted upon him.

- The conquest strategy and institutions perfected in Mexico were eagerly adopted across the Spanish Empire.

- Pizarro’s conquest of Peru exemplified the effectiveness of this approach:

- In 1531, Francisco Pizarro set out to conquer Peru, intending to replicate the strategies and tactics used by other Spanish adventurers in the New World.

- Francisco Pizarro began his conquest near the Peruvian town of Tumbes and marched south.

- On November 15, 1532, Pizarro reached the mountain town of Cajamarca where the Inca emperor Atahualpa was encamped.

- Atahualpa, having just defeated his brother Huáscar, came with his retinue to meet the Spanish on November 16, 1532.

- Atahualpa was irritated due to news of Spanish atrocities, such as violating a temple of the Sun God Inti.

- The Spanish laid a trap, killing Atahualpa’s guards and retainers (up to 2,000 people) and captured the king.

- To gain his freedom, Atahualpa promised to fill one room with gold and two rooms with silver.

- Despite fulfilling this promise, the Spanish strangled Atahualpa in July 1533.

- In November 1533, the Spanish captured the Inca capital of Cusco, imprisoning and killing the Incan aristocracy if they failed to produce gold and silver.

- The Spanish stripped Cusco’s artistic treasures, like the Temple of the Sun, of their gold, melting it into ingots.

- The Spanish divided the people of the Inca Empire into encomiendas, granting one to each conquistador who accompanied Pizarro.

- The encomienda was the main labor control and organization institution during the early colonial period.

- In 1545, Diego Gualpa discovered a massive silver ore mountain, El Cerro Rico (The Rich Hill), in present-day Bolivia.

- The discovery of silver led to the rapid growth of Potosí, which reached a population of 160,000 by 1650.

- To exploit the silver, the Spanish required a large number of miners.

- Francisco de Toledo was sent as a new viceroy in 1569 to solve the labor problem.

- De Toledo spent five years traveling and investigating his new charge and commissioned a massive survey of the adult population.

- De Toledo relocated nearly the entire indigenous population into new towns called reducciones to facilitate labor exploitation.

- He revived and adapted the Inca labor institution known as the mita, which means “a turn” in Quechua.

- The Incas used the mita for forced labor on plantations, providing food for temples, the aristocracy, and the army, in exchange for famine relief and security.

- De Toledo’s adaptation, especially the Potosí mita, became the largest and most burdensome labor exploitation scheme during the Spanish colonial period.

- The Potosí mita’s catchment area covered about 200,000 square miles, including parts of modern Peru and Bolivia.

- One-seventh of the male inhabitants in this area were required to work in the mines at Potosí.

- The Potosí mita endured throughout the colonial period and was abolished in 1825.

- The catchment area of the mita overlapped significantly with the heartland of the Inca Empire, including the capital Cusco.

- The legacy of the mita system is still evident in modern Peru, especially in the differences between the provinces of Calca and Acomayo.

- Both provinces are high in the mountains and inhabited by Quechua-speaking descendants of the Incas.

- Acomayo is significantly poorer, with its inhabitants consuming about one-third less than those in Calca.

- The road to Calca from Cusco is surfaced, while the road to Acomayo is in disrepair and further travel requires a horse or mule.

- People in Calca grow crops for the market, whereas in Acomayo, they grow food primarily for subsistence.

- These inequalities stem from historical institutional differences, particularly the inclusion of Acomayo in the Potosí mita catchment area, unlike Calca.

- De Toledo consolidated the encomienda system into a head tax, payable annually in silver by each adult male, to force people into the labor market and reduce wages.

- The repartimiento de mercancias, introduced by de Toledo, involved the forced sale of goods to locals at prices set by Spaniards.

- The trajin system forced indigenous people to carry heavy loads of goods for Spanish business ventures, substituting for pack animals.

- Throughout Spanish colonial America, similar institutions emerged, designed to exploit indigenous peoples.

- Institutions like encomienda, mita, repartimiento, and trajin aimed to reduce indigenous living standards to subsistence levels and extract excess income for Spaniards.

- These institutions expropriated land, forced labor, imposed low wages, high taxes, and high prices for goods, contributing to wealth for the Spanish Crown and the conquistadors.

- Despite generating significant wealth for the Spanish, these exploitative institutions also created deep inequality and hindered economic potential in Latin America, making it the most unequal continent in the world.

… TO JAMESTOWN

- As Spain began its conquest of the Americas in the 1490s, England was a minor European power recovering from the Wars of the Roses.

- England was in no position to join the scramble for loot, gold, and the exploitation of indigenous peoples in the Americas.

- Nearly a century later, in 1588, England’s lucky rout of the Spanish Armada marked a turning point, signaling growing English naval assertiveness.

- This naval victory enabled England to finally partake in the quest for a colonial empire.

- The English began their colonization of North America around the same time, being latecomers in the colonization race.

- They chose North America not for its attractiveness but because it was what was available; the more desirable parts of the Americas had already been occupied.

- The more profitable areas with plentiful indigenous populations and gold and silver mines were already taken by other European powers.

- English colonization efforts started with the failed Roanoke colony in North Carolina between 1585 and 1587.

- In 1607, the English tried again with three vessels, Susan Constant, Godspeed, and Discovery, under Captain Christopher Newport, heading for Virginia.

- The colonists, under the Virginia Company, sailed into Chesapeake Bay, up a river named the James, and founded Jamestown on May 14, 1607.

- The English settlers’ model of colonization was influenced by the Spanish template set up by Cortés, Pizarro, and de Toledo.

- Their initial plan involved capturing the local chief to use him to secure provisions and coerce the population into producing food and wealth for them.

- When the English colonists first landed in Jamestown, they were unaware they were within the territory claimed by the Powhatan Confederacy, led by King Wahunsunacock.

- Wahunsunacock’s capital was at Werowocomoco, only twenty miles from Jamestown, making the colonists’ presence known to him quickly.

- The colonists’ initial plan was to explore the land, hoping to obtain food and labor from the locals or engage in trade rather than farming for themselves.

- Wahunsunacock, wary of the colonists’ intentions, initially sent messengers expressing a desire for friendly relations.

- By winter 1607, food shortages plagued Jamestown, exacerbated by the indecision of the colony’s leader, Edward Maria Wingfield.

- Captain John Smith emerged as a pivotal figure, known for his adventurous background and previous military experiences in Europe.

- Smith took charge, organizing trading missions that secured essential food supplies for the colony.

- During one mission, Smith was captured by Opechancanough, Wahunsunacock’s brother, and taken to meet the king at Werowocomoco.

- Smith’s life was reportedly spared, potentially due to the intervention of Wahunsunacock’s daughter, Pocahontas, during their initial meeting.

- Freed on January 2, 1608, Smith returned to Jamestown, which remained in dire need of food until Newport’s timely return from England later that day with supplies.

- The colonists of Jamestown persisted in their quest for gold and precious metals in 1608, despite the clear lesson that relying on coercing or trading with the locals for food was unsustainable.

- Captain John Smith, recognizing the futility of this approach, noted that the indigenous people of Virginia had no gold and that food was their primary wealth.

- Anas Todkil, another settler, echoed Smith’s frustration, describing the singular focus on digging and refining gold to the exclusion of all other efforts.

- When Captain Newport returned from England in September 1608 with orders to assert firmer control over the locals, the Virginia Company’s plan included crowning Wahunsunacock to subdue him under English authority.

- Wahunsunacock, however, refused to risk capture and rebuffed the colonists’ overtures, declaring his own sovereignty and imposing a trade embargo on Jamestown.

- Newport and Smith attempted to crown Wahunsunacock at Werowocomoco, but the event was a failure, solidifying Wahunsunacock’s determination to expel the colonists.

- Newport sailed back to England in December 1608 with a letter from Smith urging the Virginia Company to abandon dreams of quick wealth and send skilled workers like carpenters, farmers, and blacksmiths instead of more gold seekers.

- Smith’s resourcefulness sustained Jamestown during this period, coercing trade from local indigenous groups or taking what was needed when trade failed.

- Smith enforced strict rules in Jamestown, stating “he that will not work shall not eat,” ensuring survival through the second winter.

- Despite Smith’s efforts, after two disastrous years, the Virginia Company restructured governance, appointing Sir Thomas Gates as the single governor to adopt a new approach.

- The winter of 1609/1610, known as the “starving time,” underscored the urgency for change as Jamestown faced starvation under Wahunsunacock’s embargo.

- John Smith, disgruntled by the new governance structure, returned to England in autumn 1609, leaving Jamestown vulnerable.

- Without Smith’s leadership, and with food supplies cut off by Wahunsunacock, the colonists faced extreme hardship, resorting to cannibalism to survive. By March, only sixty out of five hundred colonists remained alive.

- Sir Thomas Dale, under the direction of Sir Thomas Gates, implemented a new and severe work regime in Jamestown, known as the “Lawes Divine, Moral and Martial.”

- These laws imposed draconian penalties, particularly targeting English settlers who disobeyed or committed crimes.

- One clause stipulated that anyone who attempted to flee the colony and seek refuge among the indigenous Indians would face the penalty of death.

- Another clause specified that theft of crops from public or private gardens, vineyards, or cornfields would be punished with death.

- A strict prohibition was enforced against selling or giving any goods produced in the colony to captains, mariners, masters, or sailors for their personal use outside the colony. This offense also carried the penalty of death.

- These laws were intended to maintain order, discipline, and control over the colonists, ensuring that resources and labor were channeled towards the colony’s survival and prosperity.

- It’s noteworthy that these severe penalties applied to ordinary settlers but not to the elite or those in positions of authority within the colony’s governance structure

- The Virginia Company, faced with the failure of coercive methods to exploit either indigenous peoples or English settlers, shifted its approach to colonial development.

- They adopted a new model where the Virginia Company owned all the land, and settlers were housed in barracks and provided rations determined by the company.

- Work gangs were organized, each overseen by an agent of the company, resembling a system close to martial law where execution was a common punishment for offenses.

- A significant aspect of the new institutional framework was the clause threatening death to those who attempted to run away from the colony.

- With the harsh work regime imposed by the Virginia Company, some colonists found living with local indigenous populations or going it alone on the frontier beyond the company’s control increasingly attractive.

- Despite the company’s attempts at coercion, the sparse indigenous population density in Virginia limited their ability to enforce strict labor regimes comparable to those in densely populated regions like Mexico or Peru.

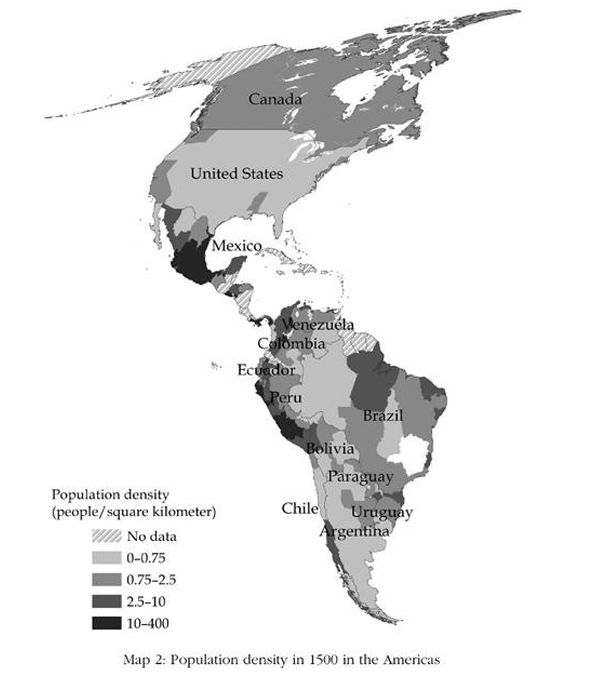

- Map 2 illustrates the population density across different regions of the Americas during the Spanish conquest, highlighting the stark contrast between regions like central Mexico and the United States in terms of population density.

- Recognizing the failure of their initial colonization model, the Virginia Company introduced a dramatic new strategy starting in 1618.

- In 1618, the company initiated the “headright system,” granting each male settler fifty acres of land and an additional fifty acres for each family member and servant brought to Virginia.

- This system aimed to incentivize settlers by providing them with land ownership and autonomy from their previous contractual obligations.

- The introduction of a General Assembly in 1619 marked the beginnings of democratic governance in the United States, giving all adult men a voice in shaping laws and institutions governing the colony.

- Despite initial failures and the realization that Spanish-style coercive systems would not work in North America, English elites persisted in attempting to establish institutions similar to those in Spanish colonies.

- The seventeenth century saw repeated efforts by English elites to impose strict economic and political controls that favored a privileged few, akin to Spanish colonial models.

- An ambitious attempt to establish such a system occurred in 1632 when Charles I granted Cecilius Calvert, Lord Baltimore, ten million acres in the upper Chesapeake Bay region, forming Maryland.

- The Charter of Maryland granted Lord Baltimore full authority to establish a government according to his own design, allowing him to enact laws without restriction (Clause VI).

- Lord Baltimore envisioned a manorial society reminiscent of seventeenth-century rural England, where large plots of land would be controlled by lords who would recruit tenants to work the land and pay rents to the elite.

- Similarly, in 1663, Carolina was founded by eight proprietors, including Sir Anthony Ashley-Cooper, who collaborated with the philosopher John Locke to formulate the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina.

- The Fundamental Constitutions aimed to create a hierarchical society controlled by a landed elite, explicitly avoiding a democratic form of government, in line with the monarchy of England.

- Both Maryland and Carolina’s experiments with elite-controlled governance encountered significant challenges and did not succeed in creating stable, economically viable colonies based on strict social hierarchy.

- The Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina established a rigid social hierarchy with “leet-men” at the bottom, who had no political power and whose descendants were perpetually designated as leet-men.

- Above the leet-men were the landgraves and caziques, forming the aristocracy. Landgraves were allocated forty-eight thousand acres of land each, while caziques received twenty-four thousand acres.

- A parliament was instituted where landgraves and caziques were represented, but it could only debate measures previously approved by the eight proprietors, limiting its effectiveness.

- Similar to Virginia, attempts to impose these hierarchical institutions in Maryland and Carolina failed due to the inability to coerce settlers into rigid societal roles amidst the expansive opportunities in the New World.

- Settlers in Maryland and Carolina demanded economic incentives and political freedoms, leading to the creation of assemblies and the erosion of proprietary control.

- In Maryland, settlers compelled Lord Baltimore to create an assembly, and by 1691, Maryland became a Crown colony, stripping Baltimore of political privileges.

- The Carolinas also experienced a struggle against proprietors, with South Carolina becoming a royal colony in 1729 due to popular pressure for more autonomy.

- By the 1720s, all thirteen colonies in what would become the United States had similar governmental structures with a governor and an assembly representing male property holders.

- While not democratic by modern standards, these assemblies granted broad political rights compared to contemporaneous societies, although women, slaves, and the propertyless were excluded from voting.

- These colonial assemblies and their leaders united to form the First Continental Congress in 1774, marking a significant step toward American independence.

- The assemblies asserted their right to determine membership and taxation, leading to tensions with the English colonial government and setting the stage for the American Revolution.

A TALE OF TWO CONSTITUTIONS

- The United States’ adoption of a democratic constitution in 1787 was rooted in the long process initiated by the Jamestown General Assembly in 1619, establishing a precedent for broad political participation and distribution of power in society.

- In contrast, Mexico’s path toward independence and constitutionalism diverged significantly. In 1808, Napoleon Bonaparte’s invasion of Spain led to the capture of King Ferdinand VII and the establishment of the Junta Central and later the Cortes in Cádiz.

- The Cádiz Constitution of 1812 proposed a constitutional monarchy based on popular sovereignty, equality before the law, and the abolition of special privileges, which challenged the entrenched power structures in colonial Latin America.

- However, the elites in South America, including Mexico, who benefited from the encomienda system and absolute power, opposed the Cádiz Constitution’s reforms, viewing them as threats to their authority and privileges.

- The collapse of the Spanish state under Napoleon’s invasion prompted a constitutional crisis in colonial Latin America, leading many regions to form their own juntas and contemplate independence from Spain.

- The first declaration of independence occurred in La Paz, Bolivia, in 1809, although it was swiftly suppressed by Spanish forces. In Mexico, the 1810 Hidalgo Revolt against colonial rule exacerbated class and ethnic tensions rather than fostering a unified independence movement.

- Mexican elites, including Creoles and Spaniards, opposed independence because it threatened their control over political and economic affairs, especially if it allowed broader popular participation as envisioned by the Cádiz Constitution.

- When King Ferdinand VII returned to power in 1815, the Cádiz Constitution was revoked, intensifying tensions between the Spanish Crown and American colonies seeking greater autonomy.

- In 1820, a mutiny within the Spanish army forced Ferdinand VII to reinstate the Cádiz Constitution, which was more radical in its proposals, including the abolition of coerced labor and the removal of military privileges.

- Faced with the prospect of these reforms being imposed in Mexico, the local elites decided to pursue independence rather than accept the Cádiz Constitution’s principles, which threatened their entrenched interests and control.

- The independence movement in Mexico was led by Augustín de Iturbide, who published the Plan de Iguala on February 24, 1821, outlining his vision for an independent Mexico as a constitutional monarchy.

- Iturbide’s plan aimed to remove the provisions of the Cádiz Constitution that threatened the status and privileges of Mexican elites, garnering widespread support and signaling Spain’s inability to halt Mexico’s independence.

- Iturbide capitalized on the power vacuum and declared himself emperor, described by Simón Bolivar as “by the grace of God and of bayonets,” consolidating his rule through military backing rather than through democratic institutions.

- Despite Iturbide’s swift rise, his dictatorship did not endure long, setting a pattern seen repeatedly in nineteenth-century Mexico where political leaders seized power outside constitutional limits.

- The Constitution of the United States, drafted in 1787, did not establish a democracy by modern standards but left voting rights to individual states. Initially, northern states granted voting rights to all white men regardless of income or property ownership, while southern states did so gradually.

- Women and slaves were excluded from voting rights, and as property and wealth restrictions on voting were lifted for white men, racial restrictions disenfranchising black men were explicitly introduced.

- Slavery was constitutionally recognized in the United States, leading to contentious debates during the constitutional convention, particularly regarding the apportionment of seats in the House of Representatives based on population.

- The Three-Fifths Compromise resolved the dispute over counting slaves for representation purposes, where each slave would count as three-fifths of a free person, appeasing southern states but perpetuating tensions between the North and South.

- Political conflicts over slavery were temporarily mitigated by compromises such as the Missouri Compromise, ensuring an equal balance of slave and free states admitted to the union to maintain Senate parity.

- These compromises preserved the functioning of American political institutions until the Civil War decisively resolved the disputes in favor of the North, leading to significant constitutional amendments and reforms.

- The period following Mexican independence in 1821 was marked by almost continuous political instability, contrasted with the United States’ relative stability. Antonio López de Santa Ana exemplified this instability, serving as president of Mexico eleven times between 1833 and 1855, often through irregular means rather than constitutional processes.

- Santa Ana’s presidency was characterized by frequent changes in power, with brief spells of leadership interspersed with periods where others assumed the presidency, leading to fifty-two presidents in Mexico between 1824 and 1867.

- This political instability severely undermined economic institutions in Mexico, resulting in insecure property rights and a weakened state unable to effectively tax or provide public services.

- The loss of territories like Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona to the United States during Santa Ana’s tenure reflected the Mexican state’s inability to exert control over its entire territory.

- Economic institutions developed during the colonial period in Mexico perpetuated inequality by exploiting indigenous populations and creating monopolies, stifling economic incentives and initiatives among the broader population.

- While the United States benefited from the Industrial Revolution in the first half of the nineteenth century, Mexico’s economic conditions worsened due to its unstable political environment and entrenched colonial economic structures

HAVING AN IDEA, STARTING A FIRM, AND GETTING A LOAN

- The Industrial Revolution began in England, initially revolutionizing cotton cloth production through mechanization powered by water wheels and later steam engines, significantly enhancing worker productivity.

- Technological breakthroughs spread from England to the United States, where entrepreneurs and businessmen eagerly adopted and adapted new technologies, fostering economic opportunities and inspiring local inventions.

- The patent system, established in England by the Statute of Monopolies in 1623 to protect property rights in ideas, played a crucial role in encouraging innovation in the United States.

- Unlike in many other nations, the United States’ patent system allowed individuals from diverse backgrounds and walks of life to secure patents, not just the wealthy elite. Many inventors, like Thomas Edison, emerged from modest backgrounds and achieved significant success.

- Thomas Edison, known for inventing the phonograph and the lightbulb and founding General Electric, came from a humble background with little formal schooling, yet he capitalized on his inventions by establishing successful firms.

- Between 1820 and 1845, a significant portion of patent holders in the United States had only primary schooling or less, highlighting the democratization of innovation in contrast to other nations.

- The democratic nature of innovation in the United States contributed significantly to its emergence as the most economically innovative nation during the nineteenth century, fostering a culture where inventive ideas could flourish across society

- Access to Capital in the United States during the nineteenth century saw significant expansion of financial intermediation and banking, supporting economic growth and industrialization. By 1914, there were 27,864 banks with $27.3 billion in assets, offering inventors ample capital at competitive interest rates.

- Role of Banks was pivotal in the US, where fierce competition ensured access to capital for entrepreneurs launching businesses based on patented inventions. Low interest rates encouraged innovation and entrepreneurship.

- Comparison with Mexico reveals stark differences. In 1910, Mexico had only forty-two banks, two controlling 60% of assets. Limited competition led to high interest rates, restricting credit access primarily to the wealthy elite.

- Political Institutions shaped Mexico’s banking sector. Post-independence instability under Santa Ana and subsequent political struggles fostered a monopolistic banking system favoring the elite.

- Porfirio Díaz’s Regime, starting in 1876, ruled Mexico authoritatively for over three decades, stabilizing the country but concentrating economic power among the privileged. This regime did not foster competitive banking or widespread access to capital.

Díaz, like Iturbide and Santa Ana, rose to power through military means, contrasting with US military leaders like Washington, Grant, and Eisenhower who respected constitutional norms.

Mexican constitutions in the 19th century lacked effective constraints on executive power, allowing leaders such as Iturbide, Santa Ana, and Díaz to wield authority unchecked by legal frameworks.

Díaz’s governance involved violating property rights, facilitating land expropriation, and granting monopolies to supporters, echoing practices of Spanish conquistadors and Santa Ana.

Both Mexico and the US had profit-driven banking industries, but Mexico’s system tended towards monopolies due to less competitive political institutions compared to the US.

In the US, competitive political institutions ensured accountability, preventing the consolidation of banking monopolies and promoting fair access to finance.

Historical attempts in the late 18th century by US politicians to establish state banking monopolies were curtailed by electoral accountability, unlike in Mexico where such monopolies persisted.

Broad political rights in the US enabled citizens to hold politicians accountable, fostering policies that supported economic prosperity and innovation.

The US banking system’s competitive nature, bolstered by political checks and balances, contributed to economic growth and innovation, contrasting with Mexico’s monopolistic and politically influenced banking practices.

PATH-DEPENDENT CHANGE

Porfirio Díaz’s administration in the late 19th century adapted to a changing global economy driven by industrialization and international trade, focusing on exporting raw materials to North America and Europe.

Unlike efforts to replicate US institutions, Díaz’s approach led to “path-dependent” changes that perpetuated existing colonial institutions rather than replacing them with more egalitarian structures.

The expansion of international trade and transportation innovations like steamships and railways reshaped Latin America’s economic landscape, benefiting elites who controlled resources.

The Americas’ newly valuable frontiers, though often mythically open, were violently seized from indigenous peoples, contributing to further divergence between US and Latin American development paths.

In the US, legislative acts like the Land Ordinance of 1785 and the Homestead Act of 1862 facilitated broad access to frontier lands, fostering egalitarian economic dynamics despite indigenous displacement.

In contrast, Latin American political institutions allocated frontier lands to the politically powerful and wealthy, reinforcing existing inequalities and concentrating power.

Díaz dismantled colonial-era restrictions on international trade to enrich himself and his supporters, mirroring historical models where elites amassed wealth while excluding others from economic benefits.

Economic growth under Díaz’s model was limited and favored the elite, echoing earlier exploitative practices seen with figures like Cortés and Pizarro in Latin American history.

The implementation of Díaz’s economic policies often marginalized indigenous groups, such as the forced deportation and enslavement of the Yaqui people to work in henequen plantations in Yucatán.

The henequen plant’s fibers were a valuable export commodity used in rope and twine production, further enriching Díaz’s regime while exploiting indigenous labor.

The persistence of institutional patterns unfavorable to growth in Mexico and Latin America continued into the twentieth century, leading to economic stagnation, political instability, civil wars, and coups.

Porfirio Díaz lost power in Mexico in 1910 to revolutionary forces, marking the beginning of the Mexican Revolution. Similar revolutions followed in Bolivia in 1952, Cuba in 1959, and Nicaragua in 1979.

Throughout the twentieth century, civil wars persisted in countries like Colombia, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Peru, fueled by struggles for political power and economic benefits.

Expropriation of assets remained prevalent, with mass agrarian reforms or attempted reforms occurring in Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Guatemala, Peru, and Venezuela.

The era saw military governments, dictatorships, and various forms of authoritarian rule across Latin America, often accompanied by revolutions, expropriations, and political instability.

Despite a gradual move towards greater political rights, most Latin American countries did not fully transition to democracies until the 1990s, and instability has continued to pose challenges.

Political instability was often coupled with mass repression and human rights abuses. For example, Chile’s 1991 National Commission for Truth and Reconciliation Report documented 2,279 political killings during Pinochet’s dictatorship (1973-1990), with thousands more imprisoned, tortured, and fired from their jobs.

In Guatemala, the Commission for Historical Clarification Report in 1999 identified 42,275 named victims of violence between 1962 and 1996, with estimates suggesting up to 200,000 deaths, including 70,000 during General Efraín Ríos Montt’s regime.

In Argentina, the National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons reported 9,000 murders by the military between 1976 and 1983, though human rights organizations estimate the actual number could be as high as 30,000.

These periods of political turmoil and violence underscored the challenges Latin American countries faced in achieving stable governance, economic growth, and respect for human rights throughout the twentieth century.

MAKING A BILLION OR TWO

Bill Gates, the founder of Microsoft, rose to become one of the wealthiest individuals globally due to the success of his innovative technology company.

Despite his entrepreneurial success, Microsoft faced significant regulatory scrutiny in the United States, particularly concerning allegations of abusing its monopoly position by tying Internet Explorer to the Windows operating system.

This scrutiny led to civil actions by the U.S. Department of Justice in 1998, indicating a regulatory environment aimed at maintaining competition and preventing monopolistic practices.

In contrast, Carlos Slim, a prominent Mexican entrepreneur, amassed his wealth through strategic investments and the acquisition of Telmex, Mexico’s formerly state-owned telecommunications monopoly.

Slim’s acquisition of Telmex, privatized in 1990 under President Carlos Salinas, was pivotal in transforming a public monopoly into a privately controlled entity.

His success highlights the different economic landscape in Mexico, where regulatory barriers and political connections can enable consolidation of economic power.

Economic institutions in Mexico pose significant barriers to entry for entrepreneurs, including costly licenses, bureaucratic hurdles, and challenges in securing funding from a financial sector often intertwined with incumbents.

These barriers either restrict competition entirely or favor those with political connections or the ability to navigate bureaucratic complexities.

The contrasting experiences of Gates and Slim underscore how institutional frameworks shape economic outcomes in the United States and Mexico.

While the U.S. regulatory environment emphasizes competition and innovation, Mexico’s environment can facilitate the concentration of economic power through strategic acquisitions and political influence.

Slim’s ability to monopolize Mexico’s telecommunications sector exemplifies how institutional legacies influence economic concentration and entrepreneurial opportunities in Latin America.

- Challenges to Carlos Slim’s Telmex monopoly in Mexico have been attempted but largely unsuccessful.

- In 1996, Avantel, a long-distance phone provider, petitioned the Mexican Competition Commission to investigate Telmex’s dominant position in telecommunications.

- The commission in 1997 acknowledged Telmex’s substantial monopoly power in local telephony, national and international long-distance calls, and other telecommunications services.

- Despite regulatory recognition of Telmex’s monopoly, attempts to curtail its dominance have failed largely due to legal maneuvers.

- Telmex and Slim utilize a legal recourse known as “recurso de amparo” or “appeal for protection,” originally intended to safeguard individual rights and freedoms under Mexican law.

- In practice, the amparo has become a tool for monopolies like Telmex to evade regulatory restrictions and cement their market dominance.

- Slim’s success in the Mexican economy has been significantly influenced by his political connections, enabling him to navigate regulatory challenges.

- However, when Slim ventured into the U.S. market with his Grupo Corso’s acquisition of CompUSA in 1999, his usual tactics did not succeed.

- Slim violated a franchise agreement CompUSA had with COC Services in Mexico, intending to establish his own chain of stores without competition from COC.

- COC Services sued CompUSA in a Dallas court, leading to a legal verdict against Slim’s actions and a hefty fine of $454 million.

- This case underscored that in the U.S., firms are required to adhere to established rules and contracts, irrespective of their international stature or connections.

- The outcome highlighted the different regulatory environments between Mexico, where amparos can shield monopolies, and the United States, which enforces its legal framework rigorously.

TOWARD A THEORY OF WORLD INEQUALITY

- Inequality between nations mirrors disparities seen between the two parts of Nogales but on a larger global scale.

- Citizens in rich countries enjoy better health, longer lifespans, higher education levels, and greater access to amenities compared to those in poorer countries.

- Infrastructure in wealthy nations includes well-maintained roads, reliable utilities like electricity and running water, and effective governance that provides essential services and upholds law and order.

- Democratic processes in affluent countries allow citizens to participate in elections and influence political decisions, contrasting starkly with situations in poorer nations.

- The vast disparities in global inequality are widely recognized, influencing migration patterns as individuals seek better living standards and opportunities in richer countries, often illegally crossing borders like the Rio Grande or Mediterranean Sea.

- These inequalities not only affect individual lives but also generate resentment and political implications, evident in countries like the United States.

- Understanding the root causes of global inequality is crucial not only for comprehension but also for formulating effective strategies to alleviate poverty affecting billions worldwide.

- Nogales, Sonora, benefits from relative prosperity compared to other parts of Mexico, largely due to maquiladora manufacturing plants located in industrial parks.

- Richard Campbel, Jr., initiated the first industrial park, attracting U.S.-based businesses like Coin-Art, Memorex, Avent, Grant, Chamberlain, and Samsonite.

- These businesses bring U.S. capital and expertise into Nogales, Sonora, contributing significantly to its economic growth and relative affluence within Mexico.

- Global disparities in prosperity are vast, with U.S. citizens being seven times wealthier than Mexicans, ten times wealthier than those in Peru or Central America, twenty times wealthier than the average sub-Saharan African, and nearly forty times wealthier than those in the poorest African nations like Mali, Ethiopia, and Sierra Leone.

- A select group of affluent countries, primarily in Europe and North America, along with Australia, Japan, New Zealand, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan, enjoy significantly higher living standards compared to the rest of the world.

- The disparity in prosperity between Nogales, Arizona, and Nogales, Sonora, is attributed to distinct institutional frameworks on either side of the border, which create differing incentives for residents.

- The United States’ higher wealth compared to Mexico or Peru is largely due to its economic and political institutions, which shape incentives for businesses, individuals, and policymakers.

- Economic institutions play a crucial role in shaping incentives such as the drive for education, savings, investment, innovation, and technology adoption.

- Political institutions determine the economic rules citizens live under and influence how these institutions function.

- The effectiveness of political institutions also dictates whether politicians serve as agents of the citizens or misuse their power for personal gain, potentially undermining citizen interests.

- Political institutions encompass written constitutions, the presence of democracy, the state’s regulatory capacity, and broader factors shaping power distribution within society.

- Understanding these institutional dynamics is essential for comprehending global inequality and formulating strategies to address poverty on a global scale.

- Institutions significantly influence behavior and incentives within societies, ultimately shaping the success or failure of nations.

- Individual talent, exemplified by figures like Bill Gates and others in the IT industry, is crucial but requires supportive institutional frameworks to translate into positive outcomes.

- In the United States, Gates and his contemporaries benefited from an educational system that nurtured their talents and economic institutions that facilitated entrepreneurship with minimal barriers.

- Economic institutions in the U.S. enabled easy company formation, feasible project financing, and competitive labor markets conducive to business expansion.

- Entrepreneurs like Gates trusted the institutions’ rule of law, secure property rights, and stable political environment, which safeguarded their investments and prevented arbitrary actions.

- Political institutions in the U.S. ensured stability, continuity, and prevented the rise of dictatorial powers that could disrupt economic activities or seize wealth.

- The book argues that while economic institutions determine a nation’s prosperity, political institutions dictate the nature of these economic institutions.

- The development of good economic institutions in the U.S. was shaped by political institutions that evolved over time, beginning after 1619.

- World inequality is explained by how political and economic institutions interact to either promote poverty or prosperity across different regions.

- Historical analysis of the Americas illustrates how institutions, once established, tend to persist and deeply influence current socio-economic conditions.

- Institutional persistence underscores the challenge of reducing global inequality and fostering prosperity in poor countries.

- Despite the pivotal role of institutions, societal consensus on institutional change is not guaranteed, often reflecting divergent interests between the powerful and broader society.

- The example of Carlos Slim highlights how entrenched interests may resist institutional reforms that could benefit broader economic growth and citizen welfare.

- Political dynamics determine which institutions prevail, emphasizing the interplay between power dynamics and institutional outcomes.

- The theory discussed in the book integrates economics and politics, examining how institutions shape national success or failure, poverty, and prosperity.

- Understanding institutional dynamics is crucial for addressing global poverty and inequality by exploring how institutions are formed, evolve, and sometimes resist change despite adverse outcomes