Chapter Info (Click Here)

Book Name – Essential Sociology (Nitin Sangwan)

Book No. – 28 (Sociology)

What’s Inside the Chapter? (After Subscription)

1. Family, Household and Marriage

1.1. Family

1.2. Household

2. Marriage and its Types

3. Lineage and Descent

3.1. Lineage

3.2. Descent

4. Patriarchy and Sexual Division of Labour

5. Contemporary Trends in Kinship Patterns, Family and Marriage

Note: The first chapter of every book is free.

Access this chapter with any subscription below:

- Half Yearly Plan (All Subject)

- Annual Plan (All Subject)

- Sociology (Single Subject)

- CUET PG + Sociology

- UGC NET + Sociology

Systems of Kinship

Chapter – 9

The family is a universal social institution, as most individuals are born into and continue to live within families, and despite changing forms, it has endured over time.

Family functions as the cradle of socialisation, where human personalities are shaped and social learning takes place.

Kinship occupies a central place in sociology because humans require emotional, physical and psychological support that kin alone can reliably provide.

Some thinkers argue that the family also restricts individual liberty and promotes values such as patriarchy.

The kinship system refers to persons recognised as relatives through consanguinity (blood), affinity (marriage), adoption and place-based relationships.

Societies with strong mechanical solidarity often have fictive kinship, where non-blood and non-marital ties develop through friendship or social obligations, as observed by S. C. Dube in Shamirpet.

Raymond Firth distinguished between effective and non-effective kin based on the degree of regular interaction.

According to Harry Johnson, kinship consists of five elements: sex, generation, closeness, blood relations and lineage.

Kinship ties are stronger in traditional societies, where kin groups perform many social functions and include institutions like family, marriage, lineage, descent, gotra and kula.

Kinship determines rights and obligations, regulates production, consumption and authority, enforces marriage taboos, and governs ritual practices.

The importance of kinship has weakened due to modernisation, including nuclear families, individualisation, migration, urbanisation and women’s empowerment.

Family, Household and Marriage

In simplest terms, family is a social unit, household is a dwelling unit, and marriage is a socially recognised union of two or more adults, and together they constitute the primary social units of society.

Family, household and marriage are regarded as the basic building blocks of social organisation.

Humans are distinguished from other animals by their capacity to marry and form families within households.

Family

Early sociologists such as Morgan and Frazer viewed the family as a product of an evolutionary process, arguing that in the earliest stage humans lived like animals and practised promiscuity, and that stable social relations gradually led to the formation of family.

This evolutionary theory was based on observations of certain communities showing promiscuous behaviour, but it is now largely rejected.

Classical sociology defined the family as a group based on marriage, common residence, emotional bonds and domestic functions, and as relations between parents and children.

The family is widely regarded as the cornerstone of society.

George Peter Murdock, in Social Structure (1949), after studying over 250 societies, argued that the family is a universal social institution.

Murdock defined the family as a social group characterised by common residence, economic cooperation and reproduction, including adults of both sexes in a socially approved sexual relationship and their children, own or adopted.

Though contested today, this definition provides a basic understanding of family as a primary social institution involving adults, reproductive relations, children, emotional bonds, consanguineal and affinal ties, household and economic cooperation.

Due to social change, classical definitions are questioned because modern families may include same-sex couples, may not perform reproduction, and many traditional functions are now taken over by bureaucratic organisations.

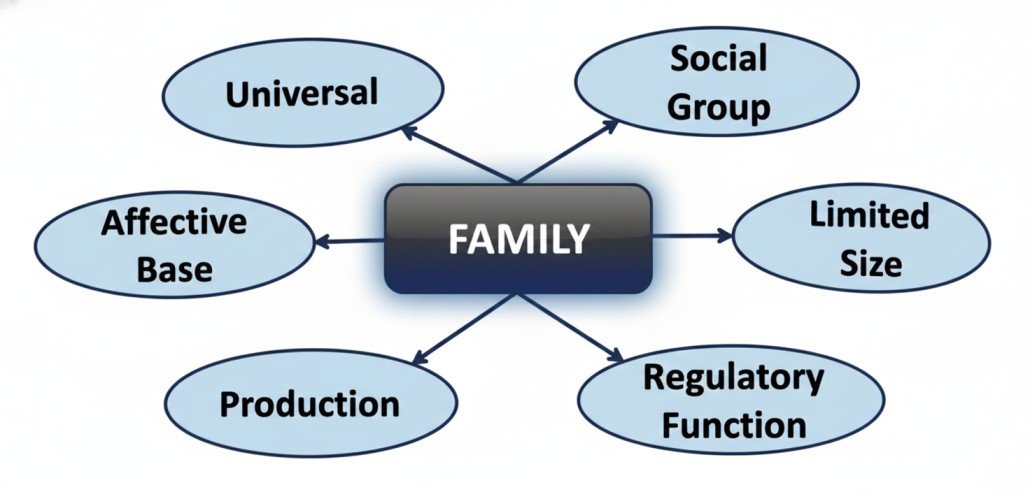

The family enjoys a unique and central position in society, and according to McIver and Page it is universal, emotionally based, limited in size, occupies a nuclear position in social structure, assigns responsibilities to members, and regulates social behaviour through early value formation.

The family is regarded as a universal and inevitable social institution and performs essential functions for both individuals and society.

George P. Murdock (1949) identified four universal functions of the family: regulation of sexual relations, reproduction, economic survival and socialisation of children.

Talcott Parsons argued that the family performs two basic and irreducible functions: primary socialisation of children and stabilisation of adult personalities, and described families as “factories of human personalities.”

Parsons viewed the modern family as an isolated nuclear family suited to industrial society due to its support for geographical mobility, but he is criticised for an overly harmonious and patriarchal bias.

Ogburn and Nimkoff listed the basic family functions as affectional, economic, recreational, protective and educational.

Ronald Fletcher (1966) argued that industrialisation has not reduced family functions and that parental responsibility has increased due to expanded social environments.

Manifest (individual) functions of the family include emotional support (personality stabilisation), physical and financial security, sexual regulation, early learning, entertainment, and social status and identity.

Latent (societal) functions include reproduction, cultural transmission, primary socialisation, social control, care of the aged and disabled, and economic production and consumption.

In contemporary society, the family is no longer the only functional unit, as many of its roles are now performed by bureaucratic institutions such as schools, hospitals, play-schools and old-age homes.

Friedrich Engels, in The Origin of Family, Private Property and the State (1884), gave a Marxist evolutionary view, arguing that in the communal mode of production family did not exist, promiscuity prevailed, and the monogamous nuclear family emerged with private property to ensure inheritance.

Feminist perspectives view the family as a site of unequal power relations and highlight the economic value of unpaid female labour, and Fran Ansley notes that women provide emotional support to frustrated men in capitalism.

Many sociologists stress the dysfunctions of family, with Morgan (1975) arguing that the family is not always a harmonious institution.

David Cooper (1972) described the family as an ideological conditioning device that restricts individual freedom, while M. Edmund Leach (1967) saw the modern family as isolated, tension-filled and emotionally stressful.

Margaret Benston argued that family perpetuates unpaid labour, and Murray Strauss stated that marriage legitimises violence, calling it a “hitting licence.”

Norman Bell (1968) concluded that children often become scapegoats for parental tensions, making the family dysfunctional for them.

With modernisation and the welfare state, social control has shifted to formal institutions, secondary functions have moved to bureaucratic agencies, production and economic placement are no longer family roles, and old-age care is increasingly institutionalised.

Although functions have changed, Ronald Fletcher argued that they have not necessarily declined, and in some areas like education, parental responsibility has even increased.

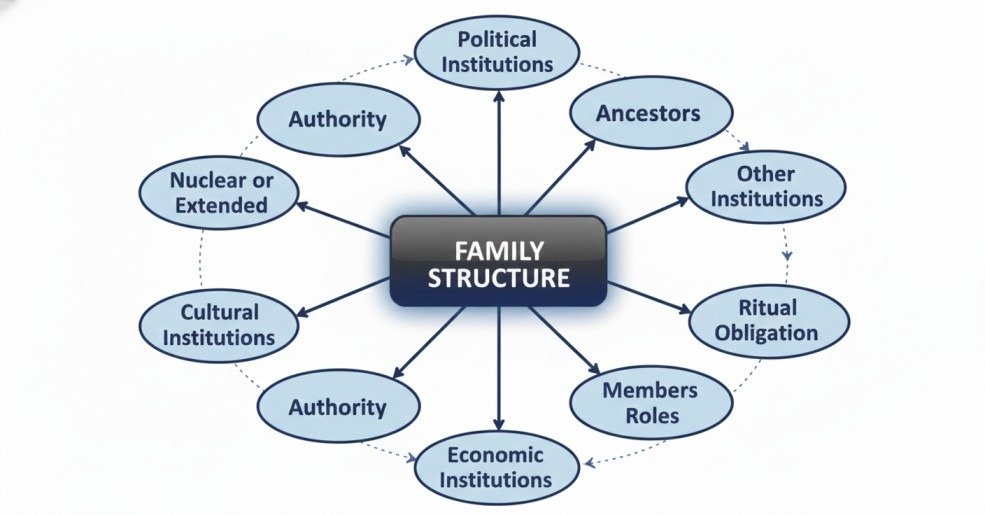

Family is also analysed through its structure, referring to size, composition and authority relations, and may be nuclear or extended, male- or female-headed, matrilineal or patrilineal.

Family structure is shaped by wider economic and social changes, such as male migration creating women-headed households and modern work schedules leading to greater involvement of grandparents in childcare.