Why Economic Geography is Good for You

Chapter – 1

Introduction

- “Mr. Daisey and the Apple Factory” was an episode of This American Life that aired on January 6, 2012, and became the most downloaded episode at the time with nearly 900,000 downloads.

- The show, hosted by Ira Glass and produced by WBEZ Chicago, typically presents stories based on a specific theme each week.

- While Ira Glass did not explicitly state the theme for this particular episode, it was clear that the focus was on economic geography.

- The episode highlighted the significance of economic geography and demonstrated the public’s interest in the topic.

- Mike Daisey, the central figure of the episode, is a self-described technology enthusiast and an avid fan of Apple products.

- Daisey expressed his deep admiration for Apple, describing himself as an “Apple aficionado,” “Apple partisan,” “Apple fanboy,” and a “worshiper in the cult of Mac.”

- For entertainment, Daisey would disassemble his MacBook Pro into its 43 components, clean them, and reassemble the device.

- Daisey’s economic geographic revelation occurred when he saw unintentional photos taken at the factory on a newly purchased iPhone.

- He realized he had never seriously considered how Apple products were made.

- The photos were taken at the Foxconn plant in Shenzhen, Southern China, near Hong Kong.

- Daisey found it remarkable that few people in America knew the name of the city where many of their products were manufactured.

- He emphasized that while people think their products come from “China” in a general sense, they actually come from specific places like Shenzhen.

- Shenzhen is not just a generalized part of China, but a distinct city where a significant amount of manufacturing occurs.

- In questioning the origins and production of Apple products, Mr. Daisey began engaging in economic geography.

- He asked where products were made, why they were made there, and how they moved geographically from their place of production to America.

- These questions are central to economic geography, prompting Mr. Daisey to acquire knowledge in the field.

- Like any economic geographer, after initial research, Mr. Daisey conducted fieldwork by visiting China and Shenzhen.

- He interviewed people and visited the Foxconn factory, though he only stood outside.

- Learning about the lives of the factory workers unsettled Mr. Daisey, challenging his initial belief that products were made by robots.

- Economic geography proved to be more complex and less soothing than disassembling and cleaning his MacBook Pro.

- Mr. Daisey realized the importance of knowing where one’s products come from and the conditions of their production.

- He understood that as a global citizen, it is important to have this knowledge.

- The text’s authors share Mr. Daisey’s enthusiasm for economic geography, describing themselves as aficionados and partisans of the discipline.

- They aim to persuade readers of the importance of economic geography, especially in the context of globalization over the past 40 years.

- Understanding economic geography is essential to grasping the changes and dynamics of the modern global economy.

- Economic geography is not just background information but is crucial to understanding the framework of economic change.

- While it doesn’t cover all aspects of life, economic geography deals with fundamental issues that support contemporary social and cultural life.

- These issues include the production and distribution of clothing, food, music, videos, and education.

- Failing to understand economic geography means missing out on understanding key aspects of contemporary life and the lives of others.

- The chapter introduces the book by pursuing larger themes and is divided into three sections.

- The first and longest section continues from Mr. Daisey’s narrative, arguing that the current juncture makes the study of economic geography especially important and relevant.

- This argument is presented in two parts:

- First, it outlines the leading features of the present moment and shows how they align with the interests and framework of economic geography, making it the right discipline for the current time.

- Second, it suggests that the discipline’s suitability comes from its evolution over the past 40 years, becoming more open-minded and adaptable while retaining historical knowledge and an ability to synthesize across different subjects.

- These qualities, along with spatial awareness, have made economic geography effective in understanding the present.

- The second section explores the meaning and implications of the book’s subtitle, “A Critical Introduction.”

- It explains what it means to think critically about economic geography by adopting two strategies:

- The first strategy involves delving behind the discipline, questioning why things are done the way they are, and examining past decisions that shape current knowledge. This includes looking at internal disciplinary processes and external historical factors.

- The second strategy provides critical evaluations of different types of economic geography, taking positions on what works well and what does not.

- The final section outlines the structure and argument of the rest of the book, which is divided into two main parts:

- The first part focuses on economic geography as a discipline.

- The second part examines the changing economic geographic world.

- The book aims to live up to its subtitle by being critical in both senses described.

“May You Live in Interesting Times”: Economic Geography’s World

Interesting times

- The phrase “May you live in interesting times” is often called the “Chinese curse,” though there’s no evidence it is Chinese or a curse.

- Contemporary economic geographers indeed live in interesting times, which have been beneficial rather than a curse for the discipline, enhancing its stature and profile.

- Six features make these times interesting for economic geography, lending themselves to disciplinary analysis.

- First, pervasive globalization is a fundamentally economically geographic phenomenon, directly relating to Mr. Daisey and the Apple factory.

- Globalization involves the increasing economic geographic integration of the world, measured by movements across national borders of:

- Goods, services, and capital

- Labor (people)

- Knowledge and information (communication)

- Cultural goods and activities (sports, cuisines, electronic games, films, music, TV shows, etc.)

- Globalization has ancient roots, with Homer writing about it around 800 BCE in The Odyssey, detailing Odysseus’s global travels.

- Despite its long history, the past 30 years have seen a quantitative and qualitative shift in globalization’s pace and form.

- Since 1980, there has been:

- A tenfold growth in world trade value in goods and services (US$2.4 trillion in 1980 to US$23.3 trillion in 2013 in constant dollars)

- A more than twentyfold increase in global foreign direct investment value (over US$1 trillion in 1980 to more than US$22 trillion in 2013)

- A doubling in the number of foreign workers globally (about 3% of the world’s population currently)

- A fiftyfold increase in the minutes US telephone subscribers spend annually on international calls (1980 to 2008)

- A shift in Hollywood film box office receipts from predominantly domestic to predominantly international (in 2014, two-thirds of receipts came from abroad)

- These changes indicate that things are not as they once were, making the present times particularly interesting for economic geographers.

- Due to its significance and inherently economic geographic nature, an entire chapter (Chapter 8) is devoted to the study of globalization and its economic geographic aspects.

- A second notable feature of our times is a communications revolution that began in the 1960s, transforming economic geographic relations.

- This revolution combined computerization with existing electronic communication forms, starting with the telegraph in the early nineteenth century.

- Computers, initially developed for military purposes during World War II and further refined during the Cold War, moved beyond military use by the mid-1950s and became essential for corporate business.

- New telecommunication technologies were initially expensive, coexisting with older forms like telegrams, which were common until the mid-1990s when email and later text messaging, Skype, and social media made telegrams obsolete.

- A third key feature involves technological improvements in physical transportation, leading to larger, faster, and more efficient vehicles (planes, trucks, boats, and trains).

- These improvements have significantly reduced freight costs, making it almost costless to move goods, according to economists Edward Glaeser and Janet Kohlhase.

- Lower transportation costs are primarily due to economies of scale with larger vehicles, such as:

- The Airbus A380, accommodating 853 passengers

- Long trains, like a 7.3 km long train in Australia with 683 rail cars

- Large trucks, like North American double trailer trucks carrying 80,000 kg

- Vast cargo ships, like the CSCL Globe, which is 400 m long, 59 m high, and carries 19,000 containers

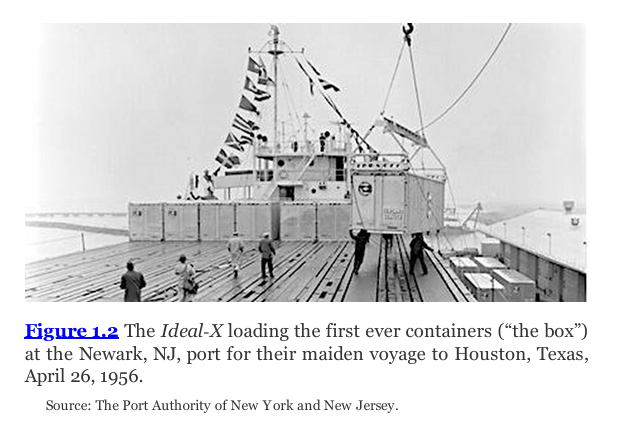

- The rise of containerization has revolutionized shipping, drastically reducing costs and shrinking the planet.

- This container revolution began on April 26, 1956, when 58 metal boxes were loaded onto the Ideal-X, a converted oil tanker, marking the start of efficient, standardized shipping containers.

- By 2002, container shipping had increased the variety of goods available to American consumers fourfold compared to 30 years earlier.

- A fourth feature is the break-up of the socioeconomic system known as Fordism during the 1970s and 1980s in the Global North.

- Fordism, pioneered by Henry Ford at his Dearborn, Michigan, automobile plant, involved mass production techniques later adopted by other industrial sectors and countries, including the UK, Germany, France, and Italy.

- Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci coined the term “Fordism” in 1934.

- After World War II, Fordist manufacturing became linked to the Keynesian Welfare State (KWS) in Global Northern manufacturing countries.

- The KWS provided Fordism with necessary resources for production, such as energy, roads, and labor (from state-owned schools and colleges).

- The government ensured people had sufficient income to buy manufactured goods, including providing income to retirees, the unemployed, and those unable to work.

- This system of Fordism and the KWS was organized nationally, with each country having its unique combination, leading to varying levels of success.

- Scandinavian countries were generally successful.

- The United Kingdom consistently lagged.

- From the early 1970s, Fordism and the KWS faced massive difficulties:

- Industrial productivity fell.

- Labor costs rose sharply.

- Profits were squeezed.

- Manufacturers in the Global North began moving operations to the Global South, attracted by low wages and facilitated by the communications and transportation revolutions.

- This shift led to the unraveling of the national-based Fordism and KWS system in the Global North, resulting in deindustrialization and the creation of rust belts.

- Tens of millions of manufacturing jobs were lost.

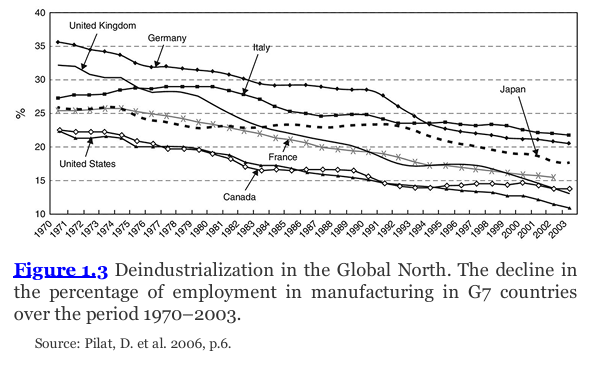

- Manufacturing employment in seven major industrialized countries in the Global North fell sharply from 1970 to 2003.

- In the United Kingdom, manufacturing employment dropped from a third of all jobs to just over a tenth.

- Former manufacturing regions, like the Upper Midwest and Northeast of the United States and northern Britain, were decimated and became shadows of their former selves.

- A new global system emerged with significant manufacturing investments in the Global South, leading to the rise of newly industrialized countries (NICs):

- Initially in Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan, and Korea.

- Later in Brazil, Mexico, Thailand, Malaysia, and China.

- These places, historically not involved in large-scale industrial manufacturing, began to do so under globalization.

- All these processes—national Fordisms and KWSs, their decline through industrial restructuring and deindustrialization, and the rise of NICs—are fundamentally economic geographic phenomena.

- These developments are ideally suited for analysis within the discipline of economic geography, providing perfect material for study.

- A fifth feature was a critical change in the nature of labor markets and work.

- Deindustrialization severely impacted Global Northern manufacturing regions from the 1970s, eliminating many relatively high-paying, often unionized manufacturing jobs typically held by men.

- Changed work practices became popular culture fodder, exemplified by the 1997 movie “The Full Monty,” later adapted into a Broadway and West End musical.

- The Global North transitioned toward a postindustrial, service-based economy, upending the older Fordist model of mass manufacturing.

- Employment now appeared in two main forms:

- McJobs: Low-paid positions requiring little skill or experience, with variations even within this category.

- Higher-end McJobs: Employment in establishments of conspicuous consumption like boutique cafes or designer clothing stores.

- Lower-end McJobs: Jobs like flipping burgers in fast-food restaurants or working as an “associate” in big-box discount retailers.

- Creative economy jobs: Often highly paid, requiring formally credentialed skills.

- Existing reconstituted sectors: Advertising, higher education.

- New sectors: Video game design, web design.

- McJobs: Low-paid positions requiring little skill or experience, with variations even within this category.

- Both types of service sector employment required embodied interactions with customers and other workers, demanding cultural, social, and emotional (soft) skills.

- In manufacturing, workers’ physical bodies were interchangeable units of labor.

- In the service sector, the body often became a crucial part of the product, with appearance, dress, comportment, speech, and looks all playing vital roles.

- Economic geography was essential in understanding:

- The global redistribution of employment, leading to a new international division of labor (see Chapter 8).

- The emergence of specialized high-tech, creative industry regions, most famously Silicon Valley in California.

- The varied micro-spaces where work was performed, such as derivatives trading rooms or Starbucks cafes.

- Finally, there is neoliberalism, which from 1980 increasingly replaced the old Keynesian Welfare State (KWS).

- Neoliberalism is a form of government that relies on market-based incentives, that is, price signals, to achieve its ends.

- Its introduction was especially associated with deregulation, which involves dispensing with government rules and laws around the economy.

- It also involves denationalization and privatization, selling off government-owned economic assets and sectors to private firms.

- The neoliberal justification is that the free market serves the economy better than the central state does.

- The state should clear the way for the market’s effective operation by removing its interference.

- The Chilean military dictator Augusto Pinochet first systematically tried out neoliberalism in his country in 1973.

- Neoliberalism as a practice became most associated with US President Ronald Reagan (1980–88) and UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher (1979–1990).

- Thatcher was especially zealous, overseeing massive privatizations of UK state-owned businesses such as railways, telecommunications, water, coal, iron and steel, and power.

- She sought to dismantle the KWS, which she called “the nanny state,” believing it pampered rather than exposed people to the necessary tough love of enterprise and the market.

- For neoliberals like Reagan and Thatcher, economic regulations imposed by countries only hindered and retarded the market.

- Therefore, individual countries and the whole world needed to be freed up for business.

- From the late 1980s, international institutions like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) imposed neoliberalism on countries of the Global South to ensure they followed neoliberal policies.

- These institutions believed that a globalized free market would be the fullest expression of the open market.

- When the market was present everywhere in the world, it would be “the end of history,” as neoliberal apologist Francis Fukuyama (1992) put it, suggesting historical change would stop and utopia was at hand.

- This also implied the end of geography, as utopia, from the Greek, literally means no place.

- It is likely the conceit of every new generation of economic geographers to believe that the period in which they entered the discipline is the most interesting.

- Economic geographers who have come of age since the 1980s have witnessed a series of wrenching and profound geographical transformations in the economy.

- The results of these transformations have varied from despair and trauma to energetic purposefulness and optimism.

- Regardless of how these changes are described, they undeniably signaled interesting times.

- Everything the discipline had previously claimed about the importance of geography became evident.

- The present moment is impossible to understand without an economic geographic sensibility.

- This is why the authors believe economic geography is good for you.

Interesting discipline

- While the times may have favored economic geography, that did not necessarily mean the discipline would seize the opportunity.

- Other social sciences were also keen to conceptualize the present economic geographic moment.

- Economic geography, always a bit shy and lacking confidence, had to up its game and assert its special contribution.

- The authors suggest that economic geography has indeed done this, becoming an interesting discipline.

- Elements making up its structure as an academic subject have allowed economic geography to take on and say something important about the present moment.

- The first such element is a recognition of, and stress on, geographical difference.

- This emphasis has been present since the discipline’s beginning.

- Doing geography meant understanding how and why one place, region, or country was different from another.

- On first blush, recognizing geographical difference might seem unhelpful when examining globalization, often presented as an inexorable, relentless power leveling geographical difference.

- Thomas Friedman, a well‐known New York Times columnist, is in that camp, suggesting “the world is flat” due to globalization.

- Globalization for Friedman is like a steamroller creating a smooth, homogeneous surface over any space it passes.

- This perspective suggests a world where everywhere is the same.

- However, economic geographers have maintained their focus on continued geographical difference and variation.

- They suggest that as globalization unfolds over space, it interacts with specific places and regions, defined by their unique combination of material and institutional forms.

- Globalization may be powerful, but it is never powerful enough to erase geographical difference altogether.

- The form that geographical difference takes may change in interaction with globalization, but it is not eradicated.

- Continuing difference makes a difference, transforming globalization into a patchwork of variegated local forms.

- The geographical world, rather than becoming a vast monolithic plain, remains spatially dappled and mottled.

- As always, geography matters.

- The second element of economic geography is its open-mindedness toward theory and method, willing to adapt in response to changing circumstances.

- In contrast, disciplines like orthodox economics appear rigid and unchanging, adhering to the same theory and method for decades.

- Orthodox economics has maintained a focus on maximizing methods based on constrained maximization for nearly 150 years.

- Economic geography, on the other hand, has reinvented itself several times throughout its history, particularly in the last 30 years.

- The discipline is characterized by its inclination to experiment with different theoretical frameworks and methodologies.

- Economic geographers select theoretical frameworks based on their relevance to the shifting geographical processes they study, rather than sticking to tradition.

- Theoretical influences in economic geography can come from science and technology studies, cultural theory, feminism, Marxism, institutionalism, or orthodox economics.

- The approach to theory construction in economic geography can be pure, drawing from a single tradition, or eclectic, combining various theoretical perspectives.

- Similarly, methods used in economic geography are diverse, ranging from statistical analysis of data to textual interpretation of interview transcripts to ethnographic fieldwork.

- The choice of methods depends on the specific object of inquiry and the nature of the data to be explained.

- Economic geography has become increasingly open about its object of study, with porous and blurred boundaries that accommodate a wide range of theories and methods.

- In contrast, orthodox economics maintains a fixed definition of its object of study with clear boundaries, distinct from the flexible approach of economic geography.

- The open-ended approach of economic geography allows it to adapt to the evolving and multifaceted character of economic activities on the ground.

- The geography of the economy is dynamic, constantly changing, and blending new combinations in diverse spaces: bodily, gendered, institutional, textual, performative, and virtual.

- Contemporary economic geography embraces this fluidity, remaining agile and capable of exploring new territories and complexities.

- This openness enables economic geography to remain relevant and exciting, capable of navigating the global complexities of the modern economy.

- Economic geography is characterized by its catholic and synthetic inclinations, encompassing a broad range of subject matter including tangible and intangible aspects, human and non-human elements, and the living and the dead.

- Historically, economic geography has aimed for geographical synthesis, integrating diverse elements found in places or regions into complex and integrated geographical entities.

- This synthetic impulse dates back to the origins of geography itself, which sought to connect and synthesize the many different aspects of places and regions.

- In contemporary economic geography, this catholic and synthetic nature is ideal for representing the present, which is marked by the collision of diverse elements in various global locations.

- Economic geography as a synthetic intellectual project strives to accomplish a mash-up of different elements, reflecting the complexity of the modern economic landscape.

- Synthesis is inherent in economic geography’s approach, making it well-suited to represent the dynamic and multifaceted nature of the present.

- Economic geography emphasizes spatial processes as fundamental and integral to understanding the objects it describes, rather than mere background atmospherics.

- Globalization exemplifies the importance of spatial processes within economic geography, where economic geographic processes have been integral since ancient times.

- Erica Schoenberger argues that economic geographic processes were essential as ancient empires like Athens and Rome attempted to globalize through military conquest.

- The expansion of these empires required economic geography to support standing armies and navies with provisions, transportation, local production, and markets.

- Today, multinational corporations (MNCs) and transnational corporations (TNCs) are the main instruments of globalization, embodying economic geographic institutions.

- MNCs and TNCs operate based on spatially differentiated processes, where different aspects of their operations are located in different places, rooted in economic geography.

- Economic geography has evolved to analyze and explain enormous changes in globalization and associated economic processes, adapting its focus to contemporary global economic dynamics.

- Overall, economic geography is well-positioned as an intellectual project to register, record, situate, analyze, and explain the complexities of the present economic and geographic landscape.

Being Critical: In What Sense a “Critical”

Introduction to Economic Geography?

- The book provides an explicitly critical introduction to economic geography.

- It distinguishes itself from other introductions by critiquing rather than simply describing the discipline.

- “Critical” derives from the Greek “kritikos,” implying judgment and discernment rather than mere contradiction.

- Critical engagement involves intellectual assessment and discrimination, not just opposing viewpoints.

- The aim is to critique economic geography using two distinct lines of questioning.

- This critique evaluates theories, methods, and concepts within economic geography.

- It involves discerning strengths, weaknesses, and implications of economic geography.

- The approach includes comparative analysis with other social sciences.

- It evaluates economic geography’s responses to contemporary economic and spatial challenges.

- Readers are encouraged to intellectually engage with economic geography’s frameworks and empirical studies.

Questioning the status quo

- Critical questioning challenges assumptions and avoids taking things for granted in economic geography.

- Historical imagination delves into the historical developments that have shaped the current state of economic geography.

- Interrogating the present involves questioning the underlying assumptions and methodologies used in economic geographic studies.

- Methodological choices are critically assessed to understand why specific research methods are chosen over others.

- Research focus scrutinizes why certain phenomena are prioritized for study while others are overlooked in economic geography.

- Determining worthiness investigates the factors influencing which topics are deemed worthy of economic geographic analysis.

- Denaturalization reveals the underlying social and cultural judgments embedded in seemingly straightforward texts or data in economic geography.

- Uncovering power dynamics examines how differential power relationships influence the production and interpretation of economic geographic knowledge.

- Example of George Chisholm’s work demonstrates how a supposedly innocuous text on commercial geography can reveal deeper complexities upon critical examination.

- Establishing economic geography as an academic discipline within British universities was a primary aim of Chisholm’s Handbook, marking scholarly territory and asserting power.

- The materiality of the Handbook itself, published by Longman, Green, and Co., served as tangible evidence of the legitimacy and substance of economic geography as a field of study.

- The text within the Handbook outlined the practices and methodologies expected of economic geographers, shaping the identity and scope of the discipline.

- Chisholm’s success in securing a position at the University of Edinburgh at age 58 underscores the Handbook’s influence in institutionalizing economic geography.

- The internal context, including Chisholm’s career trajectory and the institutionalization of economic geography, is integral to interpreting the Handbook’s significance.

- External context, such as British imperialism at its peak, profoundly influenced Chisholm’s work, reflected in the statistics, maps, and commodities discussed in the Handbook.

- The text of the Handbook cannot be divorced from its colonial context; it reflects and reinforces colonial ideologies and practices, requiring critical analysis.

- A critical introduction to economic geography involves questioning the existing norms, theories, and texts of the discipline, and subjecting them to thorough scrutiny and assessment.

- Worrying away at the status quo of economic geography means critically examining its institutional foundations, theoretical frameworks, and intellectual practices to uncover underlying assumptions and power dynamics.

Critical evaluation

- This book’s approach involves evaluating different forms of economic geography rather than simply describing them, aiming to assess their usefulness and validity critically.

- It questions whether various economic geographic approaches fulfill their intended purposes and whether they lead the discipline in productive directions.

- The decision to offer evaluations instead of mere descriptions stems from the understanding that textbooks inherently influence how a discipline evolves by shaping perspectives and practices.

- The authors aim to contribute positively and constructively to the future development of economic geography, driven by a genuine passion and commitment to the discipline.

- Unlike knee-jerk reactions or simple contradiction, the evaluations in this book are grounded in careful judgment and discernment, following Wendy Brown’s perspective of critique as a process of “sifting and distinguishing.”

- Critique in this context is not about rejecting or demeaning its object but reclaiming it for a different intellectual or practical endeavor.

- The goal is to affirm the aspects of economic geography that show promise while challenging those that might be leading the discipline astray or stagnating its progress.

- The primary aim of this book is to offer a lively, relevant, and discerning introduction to economic geography based on the authors’ perspectives and insights.

- The critique provided in the book reflects the authors’ viewpoints and values, which inevitably shape their analysis and judgments.

- Unlike a detached or neutral assessment, the critique is grounded in the authors’ particular perspectives and experiences within economic geography.

- Richard Bernstein’s question about critique in the name of what prompts the authors to be transparent about the underlying principles guiding their evaluations.

- The authors strive for honesty and transparency by clearly stating the basis upon which they critique different strands of economic geography.

- Each evaluation is explained in terms of why the authors find it fair or useful, ensuring readers understand the rationale behind their assessments.

- By contextualizing their critiques within their own intellectual framework, the authors aim to offer readers a clear understanding of the book’s perspective on economic geography.

Outline of the Book

- The book is divided into two main parts: the first explores economic geography as a discipline, while the second delves into specific substantive topics within economic geography, all approached with a critical perspective.

- Unlike typical textbooks that may gloss over internal workings and intellectual character of a discipline, this book argues for the importance of understanding these aspects.

- Discussions about the makeup and character of economic geography are not just about arcane details but involve compelling and politically charged discussions.

- Understanding the discipline’s internal dynamics is crucial because economic geography actively produces knowledge rather than passively reflecting the outside world.

- The first part of the book aims to illuminate the disciplinary imperatives that shape economic geographic knowledge, including its local rules, history, internal sociology, and intellectual geography.

- While the book focuses on economic geography written in or translated into English, it acknowledges its limitations, particularly in its coverage of non-English-speaking parts of the world.

- Despite its focus on Anglo-North American economic geography, the book recognizes the increasing global participation in English-language publications by scholars from non-English-speaking regions.

The book’s first part delves into economic geography as a discipline, emphasizing critical examination rather than mere description. It challenges traditional views that neglect the discipline’s internal workings and its intellectual character, arguing that understanding these aspects is crucial for comprehending how economic geographic knowledge is produced and shaped.

Chapter 2 critically discusses various definitions of economic geography and their implications, offering a provisional definition while advocating for ongoing debate and critique. It views economic geography not merely as a set of institutional structures or specific subject matter, but as an intellectual sensibility or perspective that evolves over time.

Chapter 3 provides a historical narrative of economic geography from its establishment as a university discipline in the late nineteenth century. It explores how internal and external forces, often influenced by power dynamics, have shaped different versions of the discipline, necessitating critical interpretation of its development.

Chapter 4 examines economic geography’s interaction with neighboring disciplines within the social sciences, arguing that this interdisciplinary space is fertile ground for critical inquiry and innovation. It challenges established disciplinary truths and encourages unconventional thinking.

Chapter 5 conducts a critical evaluation of the role and evolution of theory in economic geography, assessing its vitality and contributions to the discipline. It highlights theoretical innovations and debates within economic geography, emphasizing their ongoing relevance and impact.

Chapter 6 sheds light on methodology within economic geography, a topic often overlooked. It explores the diverse range of methodologies available and their critical potential in advancing the discipline’s analytical capabilities.

Chapter 7 offers insights into economic geography as a practiced discipline, revealing its complex interactions with material objects, abstract ideas, human activities, and social institutions. It portrays the discipline’s messy yet effective approach to understanding economic phenomena in real-world contexts.

The book’s second part focuses on core substantive topics within economic geography that are pivotal in the twenty-first century economy. It applies a critical perspective to each topic, examining their theoretical underpinnings and empirical significance while challenging conventional interpretations.

Overall, the book maintains a consistent critical stance throughout, aiming to provide a comprehensive, lively, and discerning introduction to economic geography. It encourages readers to question assumptions, evaluate perspectives, and appreciate the dynamic nature of the discipline as it evolves in response to contemporary economic challenges.

Chapter 8 delves into globalization and the disparities in economic development. It contrasts conventional views, such as Friedman’s flat-earth geographies, with economic geographers’ perspectives that emphasize the uneven and imbalanced nature of the global economy.

Chapter 9 explores modern finance and money within the context of the global economy, arguing for the indispensable role of a geographical perspective in understanding financial phenomena in contemporary times.

Chapter 10 focuses on cities as crucial components of the modern economy. Economic geography provides unique insights into urban dynamics, highlighting cities’ roles in shaping economic processes and outcomes.

Chapter 11 shifts to the environment, emphasizing its centrality to economic processes. It discusses how capitalism could differ if it adopted alternative approaches to nature, challenging current trends of privatization and commodification.

Chapter 12 examines technological and industrial changes through an economic geographic lens. It argues that these transformations are inherently geographical and require comprehensive analysis to grasp their full implications.

Chapter 13, the conclusion, underscores two overarching themes of the book. Firstly, economic geography’s ability to connect diverse phenomena into a cohesive framework rather than narrowing its scope. Secondly, it emphasizes the book’s critical approach, aiming not only to critique but also to foster positive change toward a more equitable and sustainable world.

Conclusion

Our textbook aims to offer a distinct perspective on economic geography by providing a critical introduction to the field.

Being critical in our context doesn’t simply mean being negative or contrary. It involves questioning, probing, and contesting established ideas and practices.

Through critical engagement, whether by excavating historical contexts, questioning assumptions, or experimenting with new ideas, we aim to foster a deeper understanding and education in economic geography.

The subtitle “critical introduction” reflects our approach to encourage readers to think critically, challenge norms, and explore diverse perspectives within the discipline.

We acknowledge the value of existing textbooks in economic geography while striving to offer a fresh and thought-provoking perspective that complements the field’s foundational knowledge.